What the government shutdown looks like inside federal prisons

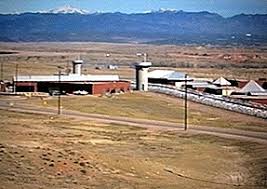

The federal supermax prison in Florence, Colorado, where inmates such as Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber, are held. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The partial U.S. government shutdown is now in its third week, due largely to President Donald Trump’s insistence that Congress give him more than $5 billion for a border wall he says will keep criminals from entering the country through Mexico.

Meanwhile, the federal employees tasked with keeping the nation safe from people convicted of crimes—prison guards—are laboring without pay.

Because the federal Bureau of Prisons is operating without funding, it has furloughed up to half of its 36,000-person staff, including many who provide therapeutic programs for prisoners and other services considered not to be “essential.” And the agency is asking its remaining employees to keep working unpaid, focusing on maintaining security even if that’s not usually their primary job.

This could remain the state of affairs until the next pay cycle in late January at the earliest—or even for months or years to come, according to Trump, who on Sunday threatened to declare a national emergency in order to bypass Congress in the funding dispute.

“It’s an absolute disaster,” said John Kostelnik, president of the American Federation of Government Employees chapter in Victorville, California, home to one of the nation’s largest concentrations of federal prison guards. “I have staff that are resorting to getting second employment—like Uber driving.”

Kostelnik points out that many federal corrections officers had already been overwhelmed by the Trump administration’s immigration policies: Victorville, for example, took in about 1,000 immigrant detainees in June.

“It was a mission that was just thrown on us,” Kostelnik said, adding that guards were not provided sufficient training or additional staff to handle the influx of detainees. “And oh by the way, now you’re not getting paid?”

In an email, the Bureau of Prisons did not respond to specific questions about conditions for officers and inmates but said the lack of funds from Congress means that only those employees whose duties involve “the safety of human life or the protection of property” are permitted to work.

The White House did not respond to a request for comment.

The shutdown is having other consequences inside federal prisons as well. At some facilities, inmate visits with their families were canceled during the holiday season due to the lack of funds, according to interviews with staff and emails with prisoners. Inmates who are terminally ill and awaiting “compassionate release” to die at home with their families now must wait even longer because their applications are going unread. And in at least one instance, a prison had to stop ordering food and toiletries for prisoners to purchase at commissary, an inmate said.

“They’re out of most of everything,” Seth Piccolo, a prisoner at the Petersburg correctional facility in Virginia, wrote in an email on CorrLinks, an app used by federal inmates. “Bad things seem to happen when prisoners don’t get their chips.”

The more urgent problem, said Robert Hood, former warden of the federal supermax penitentiary in Florence, Colorado—where inmates such as Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber, are held—is the possibility of mental-health staff being furloughed for a significant period of time.

“Most [Bureau of Prisons] facilities will run without the myriad of programs normally offered” to address the needs of dangerous or mentally ill prisoners, Hood said.

Another developing consequence of the shutdown is that the First Step Act, a celebrated prison-reform bill signed by Trump last month, may now partially be put on hold. According to the new law, the federal prison system has 210 days to develop a risk-assessment tool for evaluating which inmates can safely be released, which was already a short time frame for it to be implemented successfully. The bureau is also supposed to be recalculating the earned “good-conduct time” that some prisoners should be getting off their sentences.

That’s now all been sidelined, said Jack Donson, a former employee of the agency for two decades who is now a consultant and regularly communicates with staff and prisoners.

Inmates are emailing prison administrators saying, “Hey, what’s going on with my sentence?” Donson said.

“There are going to be inmates who are past their correct release date,” he said, “and that will manifest in frustration and them acting out.”

The Bureau of Prisons said in a statement that it will continue to work on the law’s implementation, including by identifying prisoners who stand to be affected.

For officers, the pain of missed paychecks is just beginning to set in. Some of those furloughed have seen the shutdown as a vacation, since it’s lasted only a few weeks thus far. But others who live paycheck-to-paycheck or have impending medical, child care, mortgage or gas bills—given their long drives to remote prisons—are feeling increasingly desperate.

Since federal prison employees can be transferred around the country, some of those most affected are ones not getting reimbursed for travel costs. Others said they are particularly concerned about going into debt; they said that could get them fired in the future, if the agency sees them as susceptible to bribes by inmates.

Don Drewett, a corrections officer in Otisville, New York, who is also the national legislative coordinator for the Council of Prison Locals, said the shutdown will cost the government more in the long run. To avoid further lawsuits like the one already filed by two prison guards on Dec. 31, the Bureau of Prisons may eventually have to pay extra overtime to everyone who’s been working unpaid.

“Here you are in this terrible setting, this slow psychological grind” of working in a prison, said Drewett, and now you have to watch the news to see if you’ll be getting paid?

“You hear about the politics of, ‘Oh it’s just $5 billion for a border wall, get over it and fund it and then we won’t have a problem.’ … Well, I find that to be a really crass, insensitive position. That’s not really understanding the human component here.”

This article was originally published by The Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization covering the U.S. criminal justice system. Sign up for their newsletter, or follow The Marshall Project on Facebook or Twitter.