To cooperate or not: That is a question for TV characters and real-life clients

The cast of “The Good Fight” on CBS All Access. Photo from MovieStillsDB.com.

The summer viewing schedule at my house stays pretty stable from year to year. My wife begins the season with ABC’s The Bachelorette (which I stomach for emotional support). That bleeds into CBS’ Big Brother (which I’ve learned to enjoy over the course of our relationship). Then we finally get to Oklahoma Sooner and Dallas Cowboy football (which my wife stomachs for emotional support). It’s a happy balance.

Some time before or after Big Brother, I came across The Good Fight on CBS. I wasn’t actively watching the episode that aired, but I caught a few scenes in passing. The only point that really got my attention involved an attorney advising her client about the procedure and process for meeting with the FBI. I made a note to go back and watch the episode in full, as I think a defendant’s cooperation with authorities is a topic well worth discussing from a practical standpoint.

The series initially aired on CBS All Access (the network’s streaming platform), and the station only recently decided to air the first season of the series on CBS proper. So, I know the scenes I saw occur sometime in the first season, but I can’t find the specific episode. Go figure.

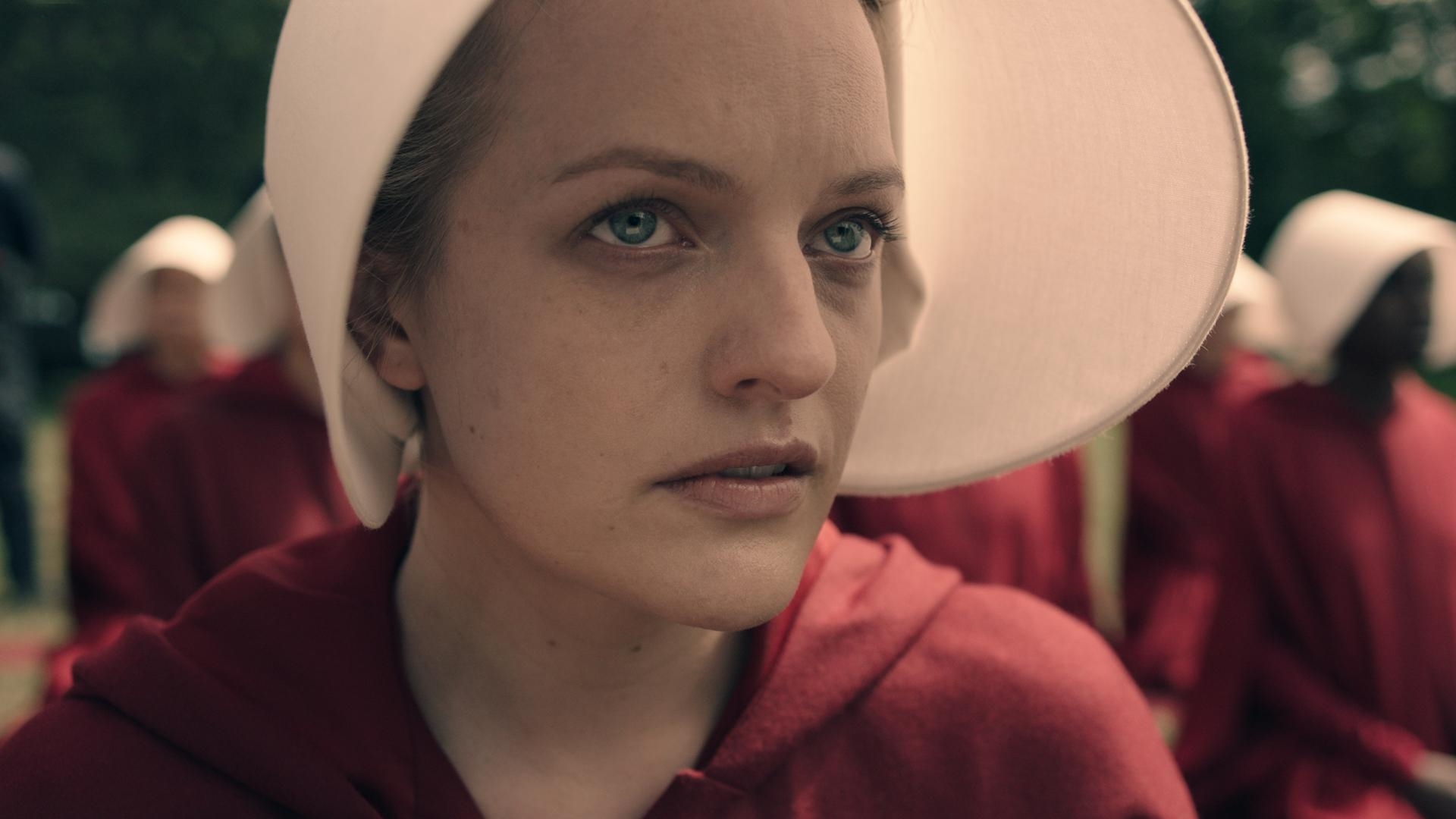

Elisabeth Moss in Hulu’s “The Handmaid’s Tale.” Photo from MovieStillsDB.com.

While my wife and I tried to locate the episode in question, she pointed out similarities with the recently aired season finale of The Handmaid’s Tale. She knows I don’t watch the show, and I’m not really interested in it, but her comments were pretty relevant to the topic at hand. Without giving away too many spoilers, in that series it sounds like someone cooperates with authorities as well, in exchange for leniency and special treatment.

Ultimately, I didn’t watch an episode from either series. But two examples of “snitching” in pop culture? That’s enough fodder to spark the flames of this week’s column.

Cooperating with authorities

The uninitiated might be surprised how often a criminal suspect or defendant cooperates with authorities. It happens fairly regularly, and the cooperation occurs in several different scenarios.

Many times, a suspect or “target” will get an opportunity to speak with the prosecution and/or law enforcement prior to facing formal charges. This happens on both the state and federal levels. In my experience, the process is much more streamlined and organized on the federal level.

The jurisdictional aspect of cooperation creates problems on the state level. In a federal prosecution, defense counsel deals with a federal agency that has jurisdiction in every state for the specific purposes of the investigation. As such, a “snitch” can give information on criminal activity and potential suspects in other states, and the investigating agency is able to extend its efforts to that area if necessary.

Cooperation isn’t always as simple on the state level, though. State prosecuting offices and law enforcement agencies aren’t usually allowed to swoop into another state (or even another county or city, depending on the agency) and follow up on a cooperating defendant’s lead. The particular agency has to reach out to an office located within the suspect jurisdiction and ask for assistance or support verifying and corroborating the information.

The coordination between state agencies is strained at best. It’s tough to get everyone on the same page, and it’s tough to keep steady lines of communication open. Many state agencies argue over who should initiate the cooperation. Some state prosecutors are happy to contact another jurisdiction to start the cooperation process. Others are opposed, and when they direct the defendant to another jurisdiction without additional guidance, the other agency has no idea what is going on due to the lack of communication.

It’s the client’s choice

Regardless, there may be times when it’s in the client’s best interest to cooperate with authorities. The client has to live with the consequences of cooperation, so the choice should be theirs and theirs alone. It is the attorney’s job to counsel the client regarding the inherent risks and potential benefits of cooperation. The client’s job is to weigh out those risks and benefits and make an informed decision they can live with.

I don’t like attorneys who strong-arm their clients into decisions regarding constitutional waivers. Cooperation with law enforcement often requires an individual to waive their Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination. Rarely will someone be in a situation to cooperate with authorities but for being investigated or arrested. Usually, the only reason a person has reliable, verifiable information is because they were involved in the activity to some degree. Otherwise, they are merely witnesses.

Therefore, an attorney should never pressure a client to cooperate. Likewise, an attorney should never pressure a client to refrain from cooperating if the opportunity presents itself and the client wishes to proceed. Our job is to advocate, mediate and advise. With that in mind, the attorney’s role in offering incriminating evidence to authorities should be in an advisory capacity.

Personally, I don’t usually bring up cooperation unless the prosecution or the client does. If the prosecution brings it up, I have to relay the offer. Otherwise, I figure if a defendant wants to talk, the defendant will let me know.

I have no problem with attorneys who say they never represent snitches, so long as they explain that before being retained and further refrain from allowing that position to affect their professional judgment. Likewise, I have no problem with attorneys who make a living off representing informants so long as the same holds true. At the end of the day, it’s the client who has to live with the repercussions.

Potential pros and cons of cooperation

You’ve all heard the anecdotes: “snitches wind up in ditches,” “snitches get stitches,” and so on and so forth. Like many expressions, there’s a bit of truth to the proclamation. In rare instances, those who cooperate with authorities face the wrath of those they “ratted” out. Prosecutors and law enforcement do their best to obtain separation orders that isolate snitches from the people they cooperated against, but sometimes that’s not enough.

An inmate who enters prison with a “snitch jacket” can face unwanted consequences from other prisoners (and guards) even if they are kept away from the inmate they cooperated against. Prisons have their own internal code of morality, and silence is golden in most circumstances. If other prisoners learn that an inmate has cooperated with authorities, they may take it upon themselves to right what they view as a serious wrong.

In all honesty, though, I’ve never had a cooperating client killed or seriously injured. I have, however, heard of other cases where the informant wasn’t so lucky. It is impossible to guarantee that an informant’s cooperation with authorities will be kept under wraps to a degree that will provide safety. Still, prison is an inherently dangerous place, and there are never any guarantees.

All things considered, a suspect or criminal defendant should not pass up an opportunity to help their situation if they are OK with weathering the potential risks. On the flip side, though, they should also never feel pressured to cooperate with authorities. While the risk of retaliation is low, it is real. For some, the benefit simply outweighs the detriment. Ultimately, it’s a personal decision that should be left to each individual. Life is short. We all have to determine how to best maximize that ticking clock.

Adam Banner

Adam R. Banner is the founder and lead attorney at the Law Offices of Adam R. Banner, a criminal defense law firm in Oklahoma City. His practice focuses solely on state and federal criminal defense. He represents the accused against allegations of sex crimes, violent crimes, drug crimes and white-collar crimes.

The study of law isn’t for everyone, yet its practice and procedure seem to permeate pop culture at an increasing rate. This column is about the intersection of law and pop culture in an attempt to separate the real from the ridiculous.