As California lawmakers cut criminal sentences, some district attorneys push back using plea deals

Image from Shutterstock.com.

After the jury deadlocked in Victor Hugo Sanchez’s murder trial in February, San Diego prosecutors offered him a deal: plead guilty to manslaughter and spend just 11 years in state prison. But there was an unusual catch. As part of the agreement, Sanchez had to sign away his right to benefit from any future legal changes, including legislation or court decisions that might reduce his sentence. He agreed.

The district attorney’s office in San Diego has proposed two more such deals, both in murder cases, but the offers were not accepted.

While the number of these pleas is small, they come at a time of tension between some “law-and-order” prosecutors and lawmakers who have been changing the state’s criminal code to try to cut the number of people in prison. Some district attorneys, including San Diego’s, have publicly pushed back on sentencing reductions.

Some lawmakers recently introduced a bill explicitly aimed at blocking the new plea deals, which they fear might become a common way to try to thwart their work. The bill’s sponsor, state Assemblyman Reggie Jones-Sawyer, a Democrat from South Los Angeles, has pushed for a public hearing.

San Diego prosecutors say they created these plea bargains to give crime victims a sense of finality. The deals will be used in “very narrow and rare circumstances that serve the interests of justice and allow victims of violent crime to have peace of mind that a court’s sentence will be carried out,” according to a statement by district attorney’s spokesman Steve Walker. He added that if Jones-Sawyer’s proposal becomes law, “we would certainly respect and follow it.”

Robert Weisberg, a criminal law professor at Stanford University, said that the deals could raise constitutional questions.

Pleas must be knowing and voluntary, he said, and it’s not clear if a person can give up rights to something that doesn’t exist yet.

“This one is pushing the envelope as far as it can go,” Weisberg said. “It’s a pretty slick and aggressive prosecutorial move.”

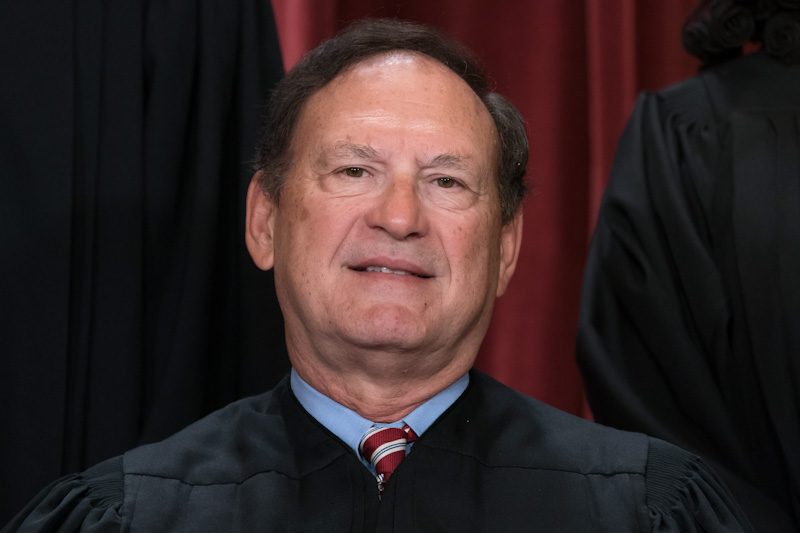

California Assemblyman Reggie Jones-Sawyer.

In March 2013, authorities arrested Sanchez in Mexico and accused him of killing a San Diego woman in 2005. His case went to trial last February, but the jury couldn’t reach a decision.

Sanchez is serving his sentence at the California Institution for Men, according to records from the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. He did not respond to an interview request.

Katherine Braner, a spokeswoman for the San Diego County Public Defender Office, declined to discuss Sanchez’s case, citing attorney-client privilege, but she described it as “a very unique situation.”

In the deal prosecutors offered Sanchez, they pointed to a 2013 California Supreme Court case that involved a man, known in court filings as John Doe, who in 1991 faced sex-offense charges. He accepted a deal that required him to register as a sex offender. At the time, only law enforcement officials had access to the registry.

Five years later, California lawmakers opened the registry to the public. The man filed a lawsuit, claiming the new legislation violated the terms of his agreement. He said he never would have taken the plea bargain if he knew his name, address and other personal information would be made public.

The court ruled against him, finding that plea agreements don’t insulate defendants from later policy changes. However, the court wrote that it could envision deals crafted so that the parties agree the terms will remain fixed even if the law changed.

The California District Attorneys Association has not taken a position on the pleas. The California Public Defenders Association opposes them.

“There’s an attempt by some district attorneys to literally thwart the will of the people,” said Margo George, co-chair of the group’s legislative committee. “Some district attorneys are trying to cling to the past.”

This article was originally published by the Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization covering the U.S. criminal justice system. Sign up for the newsletter, or follow the Marshall Project on Facebook or Twitter.