Why the prison population is so vulnerable to COVID-19

As coronavirus spreads through Florida, Jack McFarland is urging officials at Madison Correctional Facility to prepare a separate dorm for himself and other older prisoners. At 64, McFarland has spent the last 28 years in prison, and his age puts him at a higher risk of serious complications should he become infected.

The Sunshine State has more than 300 cases, and McFarland is worried about guards and staff bringing coronavirus into the prison. As the threat intensifies, he fears older people behind bars are being left to fend for themselves.

“They have no plans for us older guys,” he wrote to the Marshall Project, using the prison’s email system. “They don’t care anything about your health. We older guys just have to take care of ourselves any way we can.”

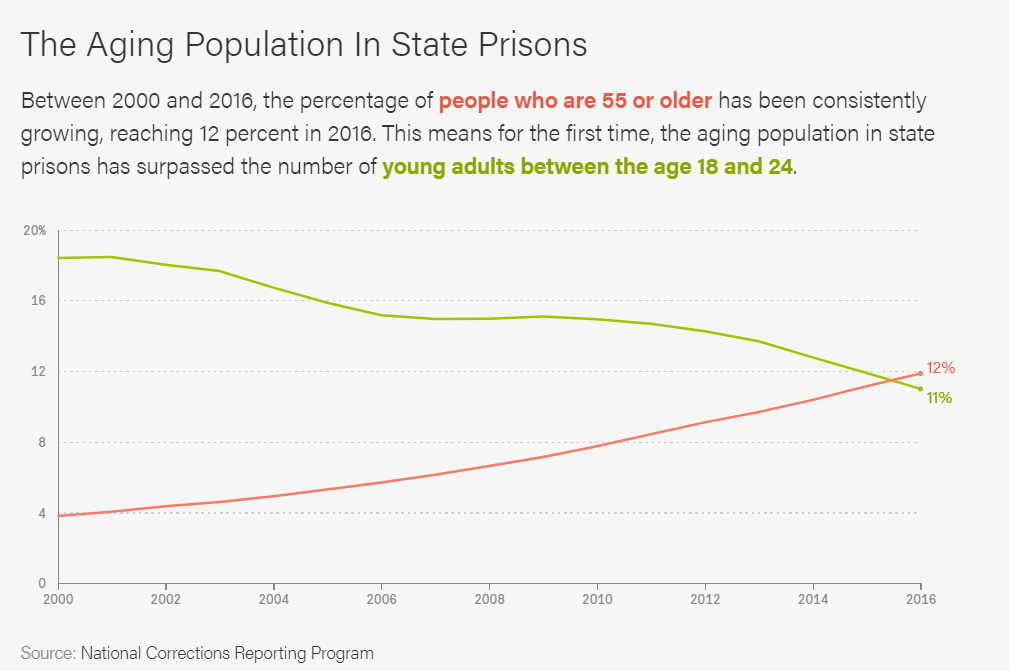

McFarland is one of a growing number of older people incarcerated across the country. The percentage of people in state prisons who are 55 and older more than tripled between 2000 and 2016, a Marshall Project analysis of data from the National Corrections Reporting Program found. Nearly 150,000 people incarcerated in state correctional facilities were 55 or older in 2016, the most recent year for which detailed data is available.

For the first time, older adults make up a larger share of the state prison population than people from 18 to 24. Similarly, 11 percent of the federal prison population—more than 20,000 people—is 56 or older, according to Bureau of Prisons data, which is collected separately from the state prisoner data.

The risk of coronavirus to incarcerated seniors is high. Their advanced age, coupled with the challenges of practicing even the most basic disease-prevention measures in prison, is a potentially lethal combination.

To make matters worse, correctional facilities are often ill-equipped to care for aging prisoners, who are more likely to suffer from chronic health conditions than the general public. As the virus spreads into the prisons, advocates and public health officials are urging corrections departments to release their aging prisoners.

Why are there so many older adults behind bars? Some scholars point to harsh sentencing laws imposed in the 1980s and 1990s as a factor.

Ned Benton, a professor of public management at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, said the popularity of “tough on crime” politics led many statehouses to enact legislation such as three-strikes and “truth in sentencing” laws. Three strike laws significantly increased sentences for people convicted of felonies, and truth in sentencing measures made sure people stay in prison for a long time before they become eligible for parole.

Florida, for example, led the nation in 2016 with one of the highest percentages of aging prisoners. Roughly 13,600 people, or 14 percent of the state’s prison population, were 55 or older, according to the Marshall Project’s analysis. For decades the state has used mandatory minimums and sentence enhancements to send people to prison for long stretches without the possibility of parole.

The Florida Department of Corrections said Thursday it is closely monitoring the spread of coronavirus, noting that there are currently no confirmed cases in the prison system. Should someone become infected, the department says it is “fully prepared to handle any potential cases.”

What was lost in the national conversation of “tough on crime,” Benton said, are the human and financial consequences of letting a generation of people grow old in prison. In 2016, a quarter of the oldest people in all state prisons were on death row or serving life sentences, and another quarter were serving sentences of 25 years or longer, the Marshall Project found.

Research shows that seniors in prison have more health issues than their younger counterparts on the outside. They suffer more often from chronic health conditions, such as hypertension and diabetes, and they’re more likely to have limited mobility and increased mental health issues.

The stress of prison life, coupled with a lack of access to quality medical care, means that many prisoners age faster than they would in the free world. By age 50, incarcerated people tend to suffer from health problems more commonly seen in people many years older.

These health conditions put them at greater risk of serious complications from COVID-19. The majority of the more than 100 people who have died from the virus in the U.S. so far were over the age of 60. Nearly 30 of the deaths occurred at a nursing home in Kirkland, Washington.

Though people of all ages have been hospitalized, scientists aren’t entirely sure why the virus is more lethal for seniors. But they suspect older people’s weakened immune systems and a higher rate of chronic health issues among the elderly play a part.

In prison, older people who require daily medications or more frequent care drive up medical costs. The annual cost of incarcerating people over 55 with a chronic or terminal illness is two to three times the cost for younger people, according to the National Institute of Corrections. Prison officials spent $8.1 billion on health care services in 2015, according to a report from Pew Charitable Trusts.

Brie Williams, a professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, said prison systems cannot and should not weather the coronavirus crisis on their own. Health departments across the country, Williams said, should include prisons in their emergency planning.

“Prison healthcare systems generally function like outpatient clinics,” said Williams, who specializes in correctional healthcare. “They have a minimum level of emergency medical equipment for a handful of people, but they don’t generally have the really serious life support machines that are needed for people in profound respiratory distress.”

In recent days, advocates have intensified their calls to release older prisoners. In a statement, the American Civil Liberties Union’s Louisiana branch urged expedited parole hearings for the elderly in state prisons.

Several conservative criminal justice reform advocates are pressing lawmakers in the Senate to introduce emergency legislation that would reduce the age at which older federal prisoners become eligible for early release from 60 to 55, noting that’s the “age at which recidivism rates drastically decline.”

Similarly, the Prison Law Office, a California law firm that provides free legal services to people who are incarcerated, has asked the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation to release people who are medically vulnerable. The Marshall Project’s analysis shows in 2016 nearly 18,000 people in the state’s prisons were 55 or older.

When asked where people would go, the Prison Law Office’s director Don Specter said, “better somewhere else than in a prison.”

Rick Storm, 59, first heard about coronavirus while watching the news in Idaho State Correctional Institution. He says prison officials have suspended visitation and barred volunteers from entering, but they haven’t provided any extra soap or cleaning supplies, and medical staff haven’t circulated any information on what they’d do should someone in the facility test positive.

A spokesperson for the prison said that officials are “taking the threat posed by COVID-19 very seriously,” noting they’ve ramped up efforts to ensure common areas are cleaned and sanitized.

Three of the state’s eight confirmed cases of COVID-19 are in Ada County, where the prison is located. As the number of new infections grows, Storm’s anxiety is rising.

“There is a lot of fear and uncertainty just like in the real world,” Storm wrote to the Marshall Project, using the prison’s email system. “Except in the real world you have a better chance of getting an answer or the proper medical treatment.”

This article was originally published by the Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization covering the U.S. criminal justice system. Sign up for the newsletter, or follow the Marshall Project on Facebook or Twitter.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.