Pro se litigants in pop culture show why representing yourself can be a dangerous decision

Image from Shutterstock.com.

The Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals has a weekly mailing list that sends out the court’s published and unpublished cases. They arrive in quick succession every Thursday morning. It’s a bit of a task to review them all, but I try to categorize the cases for future research.

The unpublished opinions can be difficult to locate after the fact. And even though they aren’t precedent, they can be reasonably persuasive to the right audience.

Most of the cases are run-of-the-mill denials of direct appeals from felony convictions, and there’s little unique or original analysis established. In most cases, the hope is simply to discover something new and potentially useful in exchange for the time spent reading the opinion.

There are rare occasions where—even if the analysis is somewhat stale—the fact patterns are interesting, for lack of a better term. Those constantly and consistently immersed in the dirt and mud of humanity’s depraved actions become somewhat numb to the extreme events they decipher day to day. For them, the gravity of a specific situation or set of facts is processed more in terms of “Have I seen this before?”

One of this week’s unpublished opinions dealt with a pro se litigant who chose to represent himself during his misdemeanor jury trial on the charge of obstruction of a public officer. He lost. He was a sovereign citizen to boot, so that added to the allure. I’ll have to take up that topic in a later column.

Pro se representation is usually one of those “Have I seen this before?” situations—not because the phenomenon is new but because you never know what a pro se litigant will do.

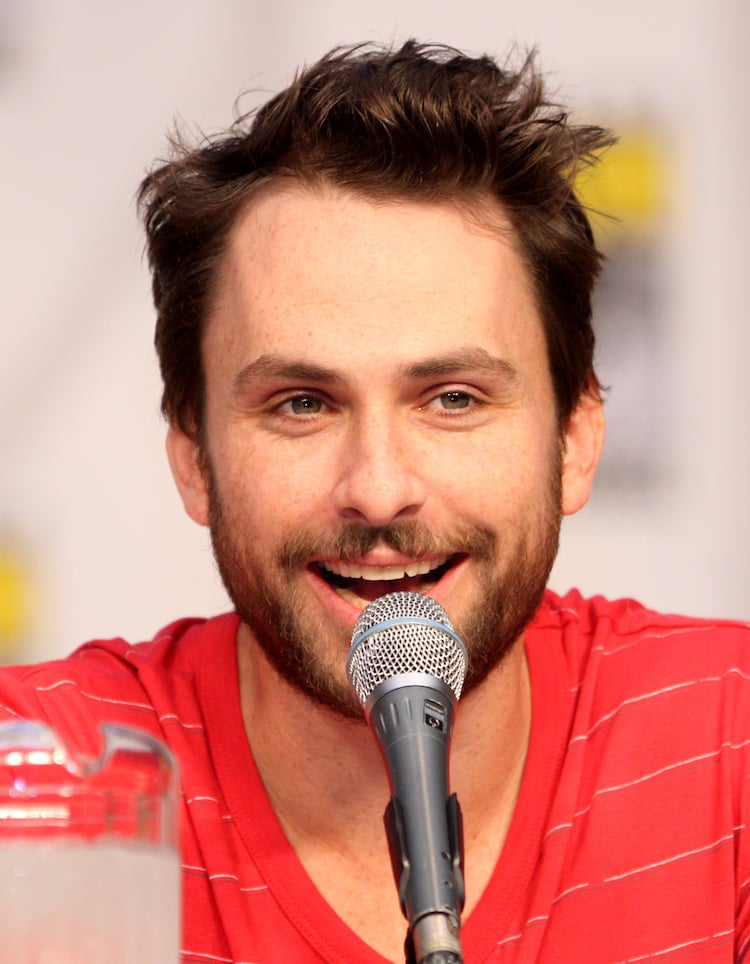

Actor Charlie Day plays Charlie Kelly in the FX series It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia. Photo from Wikimedia Commons.

Actor Charlie Day plays Charlie Kelly in the FX series It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia. Photo from Wikimedia Commons.

Pop Culture portrayals

There’s an adage often attributed to President Abraham Lincoln: A man who “represents himself has a fool for a client.” Honestly, that’s probably true, whether that client is a trained attorney or a layperson. Objectivity is a necessity.

Even though individuals represent themselves in legal battles every day in the United States, for whatever reason, that aspect of the judicial system is rarely portrayed in pop culture. Sure, there are a few examples to choose from, such as “participants” on afternoon court TV shows, such as Judge Judy and other “syndi-courts.” Outside those occurrences, though, pro se litigation isn’t as pervasive as other facets of legal advocacy.

Whenever I think of pro se litigation, my mind always comes back to Charlie Kelly from the FX series It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia. For those unfamiliar with the often crude, consistently dark comedy series now in its 14th season, Charlie Kelly (played by Charlie Day) is a lovable nincompoop who often finds himself as the butt of other characters’ jokes.

His poor hygiene, horrible life choices and penchant for constant confusion cloud the fact that the illiterate and excitable addict is somewhat of a savant in other areas of life. Practicing law is not one of those areas.

Throughout the series, Charlie often finds himself (mostly purposefully) cast as the attempted foil to “the Lawyer”—an actual attorney (in the series at least) who makes cameos from time to time.

Charlie does his best to match wits with “the Lawyer,” but he always seems to be a few steps—or miles—behind his learned opposition. Here’s a great example if you’ve never seen Charlie’s legal skills in action. To be fair, Charlie is inexplicably representing another individual, as opposed to himself, in that clip. I’m sure you’ll get the picture, though.

Pro Se Litigants in Actual Practice

Charlie’s performance may seem a bit outlandish, but it is illustrative. Anyone who’s seen a person without a proper legal education and training practice in a contested hearing or trial knows firsthand the potential for disaster.

Pro se litigants are held to much the same level of competence as actual attorneys, and many individuals underestimate the skill and talent necessary to impeach witnesses, admit evidence and otherwise advocate professionally. “Lawyering” consists of much more than a few buzzwords and legalese.

Courthouses across the country are full of stories recounting the exploits of those foolish enough to represent themselves. One of my favorites involves the man who represented himself at a jury trial against the charges of first-degree burglary and armed robbery. While the victim testified, she explained that, after the assailant tied her up and looted the house, he helped himself to a soda in the fridge. On cross-examination, the pro se defendant was quick to take issue with that statement: “Ma’am, isn’t it true that you actually offered me that soda?”

In the same vein is the tale of the pro se defendant cross-examining an eyewitness. After the witness identifies the defendant in open court and direct examination concludes, the pro se defendant gathers himself and approaches the podium. His demeanor is calm and collected. He’s ready to impeach his accuser: “Sir, how could you even know it was me since I was wearing a mask?”

The list goes on. Now, these could merely be old wives’ tales passed down in the criminal defense community. But they cut to the heart of the ultimate issue with pro se litigation. After all, not every licensed practicing attorney is skilled at trial advocacy. If the task is complicated enough that even a trained professional can lose their way, how can someone with no training navigate the situation?

The Benefits of Trained Counsel

Regardless, sometimes self-representation is a necessity based on the setting and what one stands to lose. A person might be forced to fight an eviction notice on their own. Plenty of folks file small-claims lawsuits and advocate for themselves. Sometimes paying an attorney isn’t worth what you stand to lose or gain.

Although I handle criminal defense cases almost exclusively, I will take a protective order case here and there. The cases are often parasitic in the sense that they live off the underlying criminal allegations. It’s fairly common to run into pro se litigants in the protective order arena.

Whether as plaintiffs or defendants, people generally don’t worry about these domestic issues to the point of hiring counsel. That has never turned out well for any of the pro se litigants I’ve advocated against, but I understand. Criminal law is an entirely different animal, though. The stakes are much higher; the winner takes years of a person’s life—human equity. To even consider representing yourself in a criminal case is close to the equivalent of tendering a guilty plea to the judge.

While individuals aren’t guaranteed counsel for civil or most domestic matters, the Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution guarantees that right in criminal cases. Now, I’ve heard all the complaints about public defenders failing to provide the attention and assistance that some feel is necessary to win their case. Many feel that they know the facts of their situation best, so they should be the ones to advocate.

Knowledge of the facts is only secondary to an understanding of the law, though. Don’t get me wrong—a successful advocate will have a good handle on both. Nevertheless, there is a hierarchy. A mediocre attorney licensed and in good standing can protect you and the court record better than an untrained individual, regardless of their knowledge of the facts.

To reiterate: Even practicing attorneys should hire attorneys to represent them. You wouldn’t operate on yourself after all, would you? Leave life-altering procedures to the professionals.

Adam Banner

Adam R. Banner is the founder and lead attorney at the Law Offices of Adam R. Banner, a criminal defense law firm in Oklahoma City. His practice focuses solely on state and federal criminal defense. He represents the accused against allegations of sex crimes, violent crimes, drug crimes and white-collar crimes.

The study of law isn’t for everyone, yet its practice and procedure seem to permeate pop culture at an increasing rate. This column is about the intersection of law and pop culture in an attempt to separate the real from the ridiculous.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.