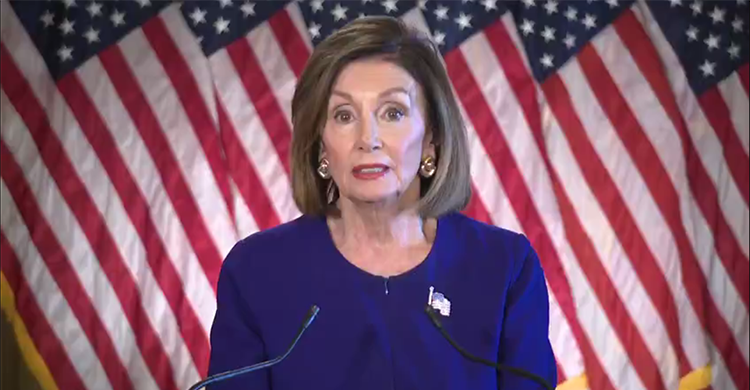

Pelosi announces Trump impeachment inquiry; could Senate refuse trial?

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi made the announcement in a video that was broadcast on Twitter.

Democratic House Speaker Nancy Pelosi announced Tuesday that the House of Representatives will begin a formal impeachment inquiry of President Donald Trump.

Pelosi said Trump has admitted asking the president of Ukraine to take actions that would benefit him politically. Such actions reveal a betrayal of the president’s oath of office; of the country’s national security; and the integrity of the country’s elections, Pelosi asserted.

“The president must be held accountable,” Pelosi said. “No one is above the law.”

Pelosi’s announcement follows news reports alleging that Trump may have pressured Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky in a July 25 phone call to open a corruption investigation into former Vice President Joe Biden and his son, Hunter Biden. The New York Times, the Washington Post and the Wall Street Journal have coverage.

Hunter Biden became a paid board member with a Ukrainian gas company called Burisma Holdings in the spring of 2014, according to prior coverage by the Wall Street Journal and the Associated Press. Joe Biden was supporting democratic efforts in Ukraine at the time. The Bidens have not been accused of any wrongdoing.

Trump said on Tuesday that he would release a transcript of the Zelensky phone call on Wednesday.

Trump has said he discussed Biden but there was no quid-pro-quo holdup of aid to the country. Trump has offered two explanations for ordering the temporary withholding of aid to Ukraine; he has said he did so because of corruption concerns with Ukraine, and that he wanted other European nations to help contribute funds.

Pelosi said Democrats want to see a complaint filed by a whistleblower that deals with the Ukraine matter, and there is a legal obligation to turn the document over to Congress.

Even if the House holds an inquiry and approve articles of impeachment, the Senate may not be in a cooperating mood, the New York Times reports in a separate story.

The Constitution allows for removal of presidents who have committed “treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.” The terms are not defined and there is no standard of proof.

Only two presidents have been impeached by the House: Bill Clinton in 1998 and Andrew Johnson in 1868. Both times the Senate failed to reach a two-thirds vote to convict on articles of impeachment, and they were allowed to finish serving their terms in office. President Richard Nixon resigned in 1974 to avoid being impeached.

In the Nixon and Clinton cases, the process began when the full House voted to authorize the House Judiciary Committee to open an impeachment inquiry. It’s not clear whether that authorization is required, according to the New York Times.

The impeachment occurs when a majority of the House of Representatives votes to approve articles of impeachment. Next, the Senate holds a trial overseen by the Supreme Court’s chief justice.

Trial procedures are set out in a Senate resolution. “Managers” from the House act as prosecutors. If at least two-thirds of the Senate finds guilt, the president is removed from office.

Could the Senate refuse to hold a trial, in the same manner it refused to hold a confirmation hearing for Supreme Court nominee Merrick Garland?

According to the Times, there is “no obvious enforcement mechanism” if the Senate majority leader refused a trial. The Republicans could simply dismiss the case, according to Duke University law professor Walter Dellinger. That could occur even if Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr.—rather than Mitch McConnell—convened the Senate to consider impeachment.

Former White House counsel Bob Bauer agreed with that assessment when he considered the issue in a Lawfare blog post in January. McConnell “would not have to look far to find the constitutional arguments and the flexibility to revise Senate rules and procedures” to block a trial, Bauer says.

“The Constitution does not by its express terms direct the Senate to try an impeachment,” Bauer writes. “In fact, it confers on the Senate ‘the sole power to try,’ which is a conferral of exclusive constitutional authority and not a procedural command. The Constitution couches the power to impeach in the same terms: it is the House’s ‘sole power.’ The House may choose to impeach or not, and one can imagine an argument that the Senate is just as free, in the exercise of its own ‘sole power,’ to decline to try any impeachment that the House elects to vote.”

See also:

Modern Law Library: What would it mean to impeach a president?

Modern Law Library: Ken Starr shares his side of the Clinton investigation in ‘Contempt’