Man who claimed to have Epstein sex tapes duped David Boies; what are the ethical implications?

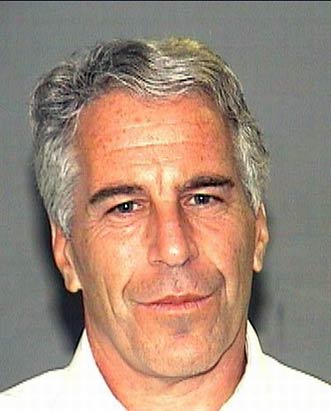

Jeffrey Epstein in 2006. Photo from the Palm Beach County Sheriff’s Office via Wikimedia Commons.

Famous lawyer David Boies was duped by a man who claimed to be a hacker with sex tapes implicating several powerful and rich men in the sexual abuse scandal involving multimillionaire financier Jeffrey Epstein.

According to the New York Times’ Nov. 30 report, Boies and another lawyer were deceived by the mystery man who called himself Patrick Kessler. The man said he had access to the materials because Epstein had hired him to set up encrypted servers to hold his digital archives, including secret sex videos.

Epstein died by suicide in jail while he was facing sex-trafficking charges.

Boies, who has been chairman and a managing partner of Boies Schiller Flexner since its founding in 1997, was representing several of Epstein’s sexual assault victims pro bono. The other lawyer, John Stanley Pottinger, also had experience representing assault victims, and his partner represented some of Epstein’s victims.

Boies and Pottinger discussed using the promised videos in litigation or to try to extract settlements from the men in the videos, with the money going to a charitable foundation, the New York Times alleged. The settlements would remain private.

When Kessler asked Pottinger to provide some hypotheticals to explain how money could be collected from those depicted in the videos, Pottinger provided two examples, according to the article.

In one hypothetical, Pottinger said the money would be split among his clients and the foundation. Up to 40% of the money would go toward attorney fees.

In the second hypothetical, the lawyers would ask the men on videotape to hire them and make a contribution to a nonprofit as part of the retainer. Hiring the lawyers would prevent the men from being sued.

David Boies. Photo by Mike McGregor.

David Boies. Photo by Mike McGregor.

Boies told the New York Times that his firm would not have gotten a cut of any settlements, but Kessler might get paid. Pottinger said his hypotheticals shouldn’t be taken at face value because he was deceiving Kessler to get the materials.

Boies and Pottinger introduced Kessler to the New York Times in a meeting that could have enhanced the lawyers’ leverage over any men in the videos. But Kessler asked to meet with the New York Times’ reporters separately and complained that he thought the lawyers would use the video to demand money from billionaires, and it looked like blackmail.

When the New York Times investigated, it found that many elements of Kessler’s story didn’t hold up. Kessler had showed the New York Times what he claimed to be classified CIA documents; they were available to anyone doing a Google search. Kessler claimed to be a 2009 investor in a North Carolina coffee company; the company wasn’t formed until 2011, and no one matching Kessler’s description was affiliated with his company. And Kessler told the New York Times that his mother and another associate were dead—then later indicated that both were still alive.

Kessler promised to produce his servers containing the files to the New York Times, then said there had been a fire and one of his team members was missing. But when Kessler spoke the same day with Pottinger, he didn’t mention any emergency.

“In the end,” the New York Times reports, “there would be no damning videos, no funds pouring into a new foundation. Mr. Boies and Mr. Pottinger would go from toasting Kessler as their ‘whistleblower’ and ‘informant’ to torching him as a ‘fraudster’ and a ‘spy.’”

The New York Law Journal spoke with ethics experts to get their take on the lawyers’ conduct as depicted by the New York Times.

The experts were concerned with Pottinger’s hypothetical in which the men in the videos would hire the lawyers. Because Boies represents several victims of Epstein’s sex-trafficking rings, representing one of the wrongdoers would pose a conflict of interest.

A spokesperson for Boies’ firm told the New York Law Journal that Boies never discussed the possibility of representing any of the abusers, nor did anyone from his law firm.

The spokesperson also said the New York Times got it wrong when it quoted Boies as saying Kessler could be generously paid.

The spokesperson also said Boies had told the FBI and federal prosecutors about Kessler, and Boies would have spoken with them and his law firm’s ethics counsel before taking steps to obtain Kessler’s supposed evidence.

Ethics experts also said that it would be unethical to use Kessler’s evidence if he had stolen it. But if Kessler was given access to the information and only breached a duty of confidentiality, the lawyers could use the information.

The spokesperson for Boies told the New York Law Journal that there would have been no problem using the evidence.

“We did not and do not believe that Epstein’s estate had any right to prevent his former IT consultant from revealing to us physical evidence in his lawful possession of crimes committed against our clients,” the statement said.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.