'Making a Murderer' subject Steven Avery loses appellate bid for new-trial hearing; his lawyer is undeterred

Steven Avery’s attorney Kathleen Zellner addresses a crowd of reporters in Making a Murderer Part 2. Photos courtesy of Netflix.

The Wisconsin Court of Appeals on Wednesday rejected a request for a hearing in a new-trial bid by Steven Avery, whose case was portrayed in the Making a Murderer Netflix series.

Avery’s current lawyer, Kathleen Zellner, remained upbeat after the decision, report the Associated Press, WLUK and Law & Crime.

“Not deterred by the appellate court decision,” Zellner tweeted. “It pointed out the specific doors that are still open for Mr. Avery’s quest for freedom. We appreciate the careful review.”

Avery was sentenced to life in prison after his 2007 conviction for killing photographer Teresa Halbach.

Her RAV4 vehicle was found on Avery’s property; her blood, along with Avery’s blood, was found in the vehicle; her RAV4 key containing Avery’s DNA was found in his bedroom; camera remnants were found in a burn pit; and a bullet and bullet fragments containing Halbach’s DNA were found in Avery’s garage.

Avery had contended that his prosecution was payback for filing a $36 million wrongful-conviction lawsuit against the county sheriff in a different case alleging rape. Avery sued after DNA evidence exonerated him in the rape and matched that of another man said to bear a “striking resemblance” to Avery.

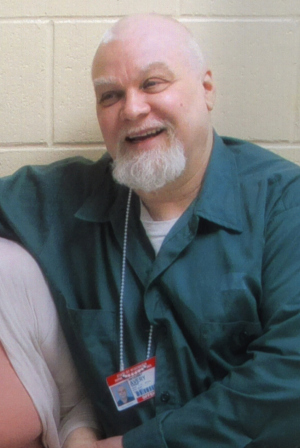

Steven Avery.

Steven Avery.At the trial for Halbach’s murder, the defense argued that police and the real killer planted evidence on Avery’s property, including the RAV4.

Avery’s nephew, Brendan Dassey, was also convicted in Halbach’s murder. He had argued that his confession was coerced, but the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear his appeal in June 2018.

The appeals court rejected six motions for collateral relief, saying they were insufficient on their face to entitle Avery to a hearing. Wisconsin law requires defendants to raise all grounds for relief in their direct appeal or first postconviction motion unless the defendant can show a “sufficient reason” for failing to raise the issue in prior proceedings.

Often, ineffective assistance of counsel is cited as the reason for failing to assert an issue on direct appeal. But there is no right to counsel in postconviction collateral review, and an ineffective assistance claim can’t be raised for failures at that stage. Avery had represented himself in his first collateral appeal, and most of his claims for his own failings can’t survive, the appeals court said.

But the appeals court said Avery could raise claims related to forensic evidence obtained with resources and extensive investigations by his postconviction counsel that he couldn’t have obtained on his own.

Even so, the new evidence doesn’t support the need for a new-trial hearing, the appeals court said. Some of Avery’s new tests and expert opinions on blood spatter evidence, DNA, the burn pit and the bullet may have been helpful at trial, but he fails to explain how the findings would have led to the conclusion that he was framed, the court said.

Key to any motion for collateral relief “are sufficient, nonconclusory showings both as to why the issue was not raised in an earlier postconviction proceeding and why the claim has facial merit,” the appeals court said. “These requirements are not optional and cannot be met through broad conclusions or by misstating evidence.

“We express no opinion about who committed this crime: The jury has decided this question, and our review is confined to whether the claims before us entitle Avery to an evidentiary hearing. We conclude that the circuit court did not erroneously exercise its discretion.”

The court said, however, Avery’s lawyer could file a new motion for collateral relief based partly on a claim that prosecutors failed to disclose a call by a paper route driver.

The driver said in an affidavit he saw Dassey and an older man pushing Halbach’s vehicle toward the junkyard days after Halbach’s death. The driver said when he called the sheriff’s office, he was told that they already knew who did it.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.