Largest public database of Chicago police misconduct allegations debuts

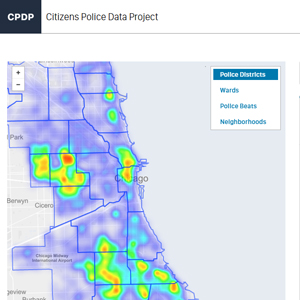

A screenshot of the Citizens Police Data Project website.

After a decade of litigation, the Invisible Institute of Chicago on Tuesday launched the Citizens Police Data Project, the largest public database of police misconduct allegations in the country.

“It’s a historic moment,” says Craig Futterman, clinical professor of law at the University of Chicago Law School and partner on the project.

The database, which includes 56,000 allegations of misconduct against 8,500 Chicago police officers, was largely made possible through Freedom of Information Act requests and civil rights litigation. It was created to bolster the conversation around reform and oversight of the Chicago Police Department.

“This is the first time there has been a complete universe of this data,” says Jamie Kalven, an independent journalist and executive director of the Invisible Institute, the journalistic production company behind the database.

The data itself sheds new light on the Chicago Police Department’s disciplinary outcomes, which Kalven says illustrates that “complaints are not being properly addressed.” For instance, the user-friendly database shows that only 2 percent of officers who received misconduct complaints between March 2011 and September 2015 were punished.

In addition, Kalven says, the database revealed that when punishments were levied, they were not proportional to the offenses. For example, the average leave for a sustained administrative violation was 16½ days, while the average punishment for a proven rape or sex offense was just six days.

Futterman says that complaints are created by a small number of officers, and that the department is not “overwrought” with bad cops. The data backs him up. “Repeat” officers, those with more than 10 complaints, make up 10 percent of the force, but 30 percent of all complaints.

The genesis of the project dates to the early 2000s. Futterman and his clinical students at the University of Chicago connected with Kalven, who was working in the Stateway Gardens public housing complex in Chicago’s South Side.

While there, Kalven says she witnessed a high concentration of “problematic officers.” The officers’ conduct ranged from over-policing and harassment to under-policing when an emergency arose, along with incidents of racism and sexism. Compounding the situation was the lack of official oversight. “I witnessed what impunity looks like,” Kalven says.

These complaints led to a number of civil rights suits brought by Futterman’s Mandel Legal Aid Clinic. One case, Bond v. Utreras, inadvertently created the database.

Diane Bond, a resident of Stateway Gardens, claimed she had been repeatedly harassed by Chicago police officers. While the case was ultimately settled, the city provided significant information about police misconduct during discovery. This information, however, was under a protective order and not public.

In a last-minute intervention, Kalven, represented by Lovey & Lovey, asked that the documents be released because they were public information. The trial judge sided with Kalven, but the Chicago-based 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals overturned the decision because Kalven lacked standing.

In a subsequent suit, Kalven v. City of Chicago, the Illinois Supreme Court found that the discipline records requested were public documents and should be released.

“This is a watershed decision,” Kalven says. It opened the door on decades of privacy around police misconduct records. Because of this case, the city of Chicago went from being an adversary to partner in this work.

“The city deserves credit,” says Futterman, who notes that the local government worked at a “granular level” to ensure the decision was appropriately implemented. City government officials did not respond to requests for comment.

The project includes three different datasets: officers with more than 10 complaints between May 2001 and May 2006; officers with more than five excessive force complaints from May 2002 to December 2008; and all officer complaints from March 2011 to September 2015.

Prompted by a freedom of information request by the Chicago Sun-Times and the Chicago Tribune, Chicago recently attempted to release all officer complaint information going back to 1967. This release is held up by a temporary injunction brought by the Fraternal Order of Police Lodge 7, a police union, and a subsequent appeal. The injunction allowed only the four most recent years of information to be released. The Fraternal Order of Police and the Chicago Police Department did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Futterman argues that the common set of information will open up the public conversation. He also strikes a cautious tone. “This database provides a powerful tool for reform, but it’s not self-executing. The release of this information doesn’t suddenly make racism or sexism within the police department go away.”