Kavanaugh praised Rehnquist's stand against unenumerated rights in Roe v. Wade dissent

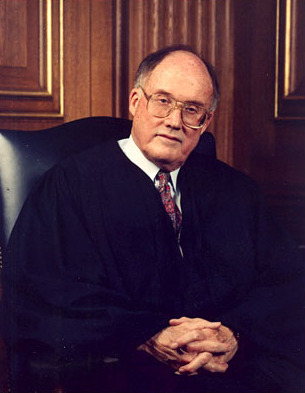

Former Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist/Wikimedia Commons.

The late Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist was Brett Kavanaugh’s “first judicial hero,” the Supreme Court nominee said in a Constitution Day speech last September.

Kavanaugh praised Rehnquist for taking a stand against unenumerated rights in the Constitution in his Roe v. Wade dissent, for his law-and-order limits on the Miranda and exclusionary rules, and for his conclusion that the “wall between church and state” was too strong, the Los Angeles Times reports. The Daily Beast followed with a story on Kavanaugh’s discussion of Roe v. Wade.

Kavanaugh talked about Rehnquist’s legacy in a speech to the American Enterprise Institute.

Kavanaugh praised Rehnquist as an “extraordinary justice” he came to admire after starting law school in 1987. “In class after class, I stood with Rehnquist,” Kavanaugh said. “That often meant in the Yale Law School environment of the time that I stood alone. Some things don’t change.”

Kavanaugh said he read a Texas Law Review article by Rehnquist that strongly influenced his understanding of the Constitution. Rehnquist believed constitutional principles don’t change absent an amendment, though such principles are applied to new developments that would have been unforeseeable to the framers.

Kavanaugh embraced that philosophy when he accepted the Supreme Court nomination Monday night.

“My judicial philosophy is straightforward,” said Kavanaugh, a 53-year-old judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit. “A judge must be independent and must interpret the law, not make the law. A judge must interpret statutes as written. And a judge must interpret the Constitution as written, informed by history and tradition and precedent.”

In his speech last year, Kavanaugh said Rehnquist applied his constitutional principles to change the law in the areas of criminal procedure, religion, federalism, unenumerated rights, and administrative law.

• On unenumerated rights, Rehnquist’s Roe v. Wade dissent took on the issue. Kavanaugh wrote:

“Rehnquist’s dissenting opinion did not suggest that the Constitution protected no rights other than those enumerated in the text of the Bill of Rights. But he stated that under the court’s precedents, any such unenumerated right had to be rooted in the traditions and conscience of our people. Given the prevalence of abortion regulations both historically and at the time, Rehnquist said he could not reach such a conclusion about abortion. He explained that a law prohibiting an abortion even where the mother’s life was in jeopardy would violate the Constitution. But otherwise he stated the states had the power to legislate with regard to this matter. In later cases, Rehnquist reiterated his view that unenumerated rights could be recognized by the courts only if the asserted right was rooted in the nation’s history and tradition.”

Judge Brett Kavanaugh.

Though Rehnquist’s view didn’t prevail, Kavanaugh said, “he was successful in stemming the general tide of free-wheeling judicial creation of unenumerated rights that were not rooted in the nation’s history and tradition.” As an example, Kavanaugh cited Rehnquist’s opinion rejecting the idea that assisted suicide was a fundamental right.

• On criminal procedure, Rehnquist “led the charge in rebalancing Fourth Amendment law to respect the rights of the people and victims of violent crime as well as of criminal defendants,” Kavanaugh said. Rehnquist didn’t succeed in overturning the exclusionary rule, and today not many people are calling for that result “given its firmly entrenched position in American law,” Kavanaugh said.

But Rehnquist led the court in creating exceptions to the rule, and also shaped the Miranda rule so it is applied in “a more commonsensical way,” Kavanaugh said.

• On religion, Rehnquist helped reverse the trend that barred religious institutions from receiving federal funds.

“Throughout his tenure and to this day,” Kavanaugh said, the Supreme Court “sought to cordon off public schools from state-sponsored religious prayers. But Rehnquist had much more success in ensuring that religious schools and religious institutions could participate as equals in society and in state benefit programs.”

• On administrative law, Kavanaugh cited Rehnquist’s separate opinion in the 1980 “Benzene Case.” Rehnquist said he would have struck down a statute giving the labor secretary expansive authority to regulate benzene and other harmful substances. The problem, Rehnquist said, was that the statute was an unconstitutional delegation of legislative power to the executive branch. The opinion didn’t become law, but it helped shape a “major rules doctrine” that says Congress may not delegate authority to agencies to issue major rules unless Congress clearly states it is doing so, according to Kavanaugh.

• On federalism, Rehnquist “led a federalism revolution,” Kavanaugh said. He focused on Rehnquist’s opinions helping establish outer limits on Congress’ ability to exercise its authority on the grounds of regulating interstate commerce. The decisions “were critically important in putting the

brakes on the commerce clause and in preventing Congress from assuming a general police power,” Kavanaugh said.

Kavanaugh cautioned that he didn’t agree with all of Rehnquist’s opinions. In particular, Kavanaugh said, he still has trouble with Rehnquist’s majority opinion in Morrison v. Olson upholding the constitutionality of the independent counsel law. Justice Antonin Scalia wrote the famous “this wolf comes as a wolf” dissent. (Kavanaugh later worked for independent counsel Kenneth Starr in an investigation of President Bill Clinton.)