ABC's 'Judd, for the Defense' and discovery obligations through the years

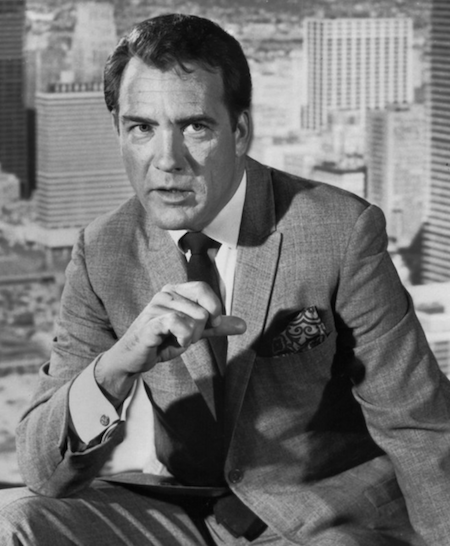

Carl Betz as Clinton Judd in Judd, for the Defense. Photo from Wikimedia Commons.

For this installment in my column, I initially set out to write one of my “look back” pieces on a legal-centric television show focused on a prosecutor. Initially, my pick was Jake and the Fatman. If nothing else, I love the show’s title. The series was in syndication from 1987 until 1992, but I couldn’t find a full episode anywhere. It’s not streaming, and it’s not on YouTube, Dailymotion, or any of my other usual go-to video aggregators. I’ll keep looking, but until then, I had to change course a bit.

‘Judd, for the Defense’

Somehow, I came across Judd, for the Defense. I can’t recall the exact rabbit hole I went down to find this gem, but safe to say, I had never heard of the series prior to that moment. In fact, when I first read the title to myself, I thought it sounded more like a comedy than anything else. Maybe it’s just the name “Judd” that I associate with the genre. I was far from the mark, though, as Judd for the Defense is a classic legal drama that fits right in with many other offerings from the time period.

Judd, for the Defense aired on ABC from 1967 to 1969. The series focused on Clinton Judd, played by Carl Betz, a skilled high-profile criminal defense attorney who took on clients charged with controversial fact patterns all across the country. Betz received some acclaim for the role over the series short tenure, eventually winning both a Golden Globe and an Emmy in 1969 for his performance.

‘The Living Victim’

Like so many lost treasures, Judd, for the Defense isn’t available on any of your standard subscription streaming services, such as Hulu and Netflix. I was able to find one episode on YouTube, though. The visual and audio quality are nothing to write home about, but the episode wastes little time in jumping right into the action.

Episode 14 of the first season—“The Living Victim”—starts off with individuals informing a man named Joe Flexner that his wife just died in an explosion. Apparently, the wife was in a car that was wired with explosives, which happens to belong to Flexner. He doesn’t seem too disturbed by his spouse’s death but instead contacts another man named Whitaker to let him know that he didn’t “get him” with the car bomb. Flexner lets Whitaker know that he’s “been trying to get [him] legally” for many years, but he’s definitely going to “get [him] now no matter what it takes.”

Whitaker has counsel, but feels that he may need additional “legal talent.” His current attorneys approach Judd with an offer of up to $50,000.00 as a retainer. Judd is offered a briefcase with the money after he balks initially, but he has no interest in the tax-free offer. The scene does a solid job of setting up two of the episode’s essential aspects for the uninitiated viewer: 1) Judd is a stand-up defense attorney with an excellent moral compass, and 2) Flexner is a district attorney who seems to be cut from the same cloth.

Shortly thereafter, Judd finds out from one of Flexner’s prosecutors that Flexner has made up his mind regarding Whitaker’s guilt, and he will do whatever it takes to convict. The prosecutor asks Judd to intervene with Flexner, and Judd obliges. He tries to talk some sense into him, but once Flexner declines, Judd decides to defend Whitaker until and unless Flexner removes himself from the prosecution.

As the episode progresses, Judd discovers that Whitaker was, in fact, not the killer and that Flexner is fully aware. Regardless, Whitaker moves forward with the prosecution until, at trial, Judd finally convinces Flexner to dismiss the case and resign from his position.

Discovery rules and obligations throughout the years

From the start, Judd asks Flexner to turn the prosecution over to the state attorney general’s office, as the victim is his wife, and he will undoubtedly be biased, but Flexner refuses. Consequently, an old friendship becomes compromised as gamesmanship takes the place of legal obligations.

Prosecutorial ethics are a subset of the ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct that states have codified to govern the conduct of practicing attorneys. Although the practice of law has been around in one form or another for centuries, the rules and obligations governing that practice are relatively recent developments. I bring that up because this episode of Judd, for the Defense went into some refreshingly real-world issues regarding prosecuting and defending cases, such as bias and potential discovery violations. I’ve previously written at least one column in this series on the subject of prosecutorial bias, so I’ll leave that alone for the time being.

At one point in “The Living Witness,” Judd confronts Whitaker regarding discovery and his professional obligations. Flexner goes as far as refusing to name a witness that will substantiate that Whitaker ordered another person to wire the bomb to Flexner’s vehicle. Judd explains that there is no way he can defend the case if he doesn’t have that information, but Flexner tells him he will have to wait until the trial or go ahead and make his pitch to the judge beforehand. In a remarkable twist, Judd is able to conduct a “pretrial examination” of sorts to do for Flexner what Flexner wouldn’t do for him: disclose his case.

As attorneys and advocates, our enumerated ethical obligations have grown over the years, not only through applicable case law but also via model rules and promulgations. All state codifications are based on the American Bar Association Model Rules of Professional Conduct (Model Rules). According to the ABA, “before the adoption of the Model Rules, the ABA model was the 1969 Model Code of Professional Responsibility,” which, in turn, was predated by the ABA’s 1908 “Canons of Professional Ethics.” The Canons of Professional Ethics drew heavily from the ethical code adopted by the Alabama State Bar Association in 1887.

Through my limited research into the topic, it appears that “discovery” methods and procedures as we know them today did not exist at common law. Various developments over hundreds of years led toward our modern understanding of the topic. Still, it wasn’t until the promulgation of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure in 1938 that the modern “discovery” system resembling our current standards was put into place.

It makes sense then that the term “discovery” doesn’t appear at all in the 1908 “Canons of Professional Ethics.” Moreover, in the 1969 Model Code of Professional Responsibility, “discovery” only appears once. That mention is in a footnote, which merely states that “an attorney’s dealings with his client … should be immune to discovery proceedings.” As such, we can glean that the ethical ramifications of discovery obligations were contemplated at that time to some degree, even if they weren’t fully fleshed out.

Nevertheless, even our current version of the Model Rules only briefly mentions the term “discovery” twice, with both occurrences in Rule 3.4: Fairness to Opposing Party & Counsel. That rule states that “A lawyer shall not … in pretrial procedure, make a frivolous discovery request or fail to make reasonably diligent effort to comply with a legally proper discovery request by an opposing party.”

Judd, for the Defense is one of the best “surprise series” I’ve stumbled upon while writing this column. Procedurally insightful and entertaining to boot, “The Living Witness” shows that, even though discovery disclosures haven’t always been an explicit aspect of professional responsibility and ethics, the abuse of the obligation has permeated the legal system for decades—just as it does today.

No matter how much some things change, they somehow manage to stay the same.

Adam R. Banner is the founder and lead attorney at the Oklahoma Legal Group, a criminal defense law firm in Oklahoma City. His practice focuses solely on state and federal criminal defense. He represents the accused against allegations of sex crimes, violent crimes, drug crimes and white collar crimes.

The study of law isn’t for everyone, yet its practice and procedure seems to permeate pop culture at an increasing rate. This column is about the intersection of law and pop culture in an attempt to separate the real from the ridiculous.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.