Netflix's new Jeffrey Epstein docuseries explores conspiracy theories and crime cover-ups

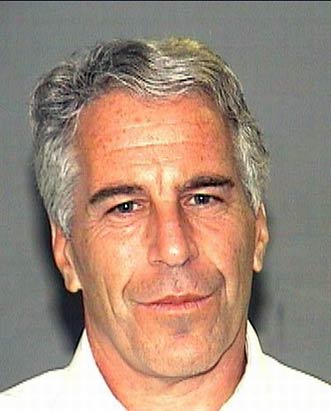

Chauntae Davies and Jeffrey Epstein in the third episode of Netflix’s Jeffrey Epstein: Filthy Rich. Davies is one of the women who had accused Epstein of sexual abuse and sexual assault. Photo from Netflix.

I honestly can’t count how many memes I’ve received via text message or social media regarding convicted sex offender and financier Jeffrey Epstein’s apparent suicide. Each photo or image that I see presents the opportunity to relay a specific message in an unexpected context. The message is almost always the same: Epstein didn’t kill himself.

The thrust of the phrase centers around the questionable circumstances surrounding Epstein’s death in a jail cell Aug. 10, 2019, as he awaited prosecution for federal sex trafficking and conspiracy to traffic minors for sex.

Breaking down ‘Jeffrey Epstein: Filthy Rich’

Consequently, I was a bit intrigued when I saw the new Netflix docuseries Jeffrey Epstein: Filthy Rich. I had followed the case to a certain degree. I was aware of the suspect plea agreement in Palm Beach County, Florida.

That deal was subsequently vacated after U.S. District Judge Kenneth Marra of the Southern District of Florida ruled that federal prosecutors had violated the Crime Victims’ Rights Act by failing to notify victims and arguably misleading them, as well. However, the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals at Atlanta recently overturned that ruling.

I was interested in watching the series to a certain degree, but my wife was the driving force. She had a bit of background knowledge of the accusations, but she wasn’t aware of the procedural history. She’d seen the same memes, however, and she remembered English comedian Ricky Gervais’ joke regarding Epstein’s alleged suicide at the 2020 Golden Globe Awards. So we decided to give it a view.

The series consists of four episodes, and it is well-produced and pretty compelling. The production team does a great job of keeping the story engaging while consistently weaving different threads of information throughout.

The allegations covered a span of almost two decades. It’s easy for a series to fall victim to continuity or clarity issues when trying to condense so many facts and allegations into approximately four hours of screen time, but the docuseries didn’t disappoint.

The first episode introduces the audience to some victims who set the stage for the common motive of abuse: the massage. The second and third episodes focus more on the initial investigation in Florida and the extremely questionable plea bargain that Epstein’s superstar team of defense attorneys were able to strong-arm out of then-U.S. Attorney R. Alexander Acosta.

The plea deal gave Epstein immunity from any federal charges, provided immunity for any named or unnamed co-conspirators, and resulted in Epstein serving only 18 months in the Palm Beach County detention facility.

There, he was almost immediately granted work release for 12 hours per day, six days per week. Epstein had to pay for an off-duty deputy to be with him all day at his office—to the tune of a $128,136 bill paid to the jail.

The fourth and final episode focuses solely on the federal lawsuit that effectively vacated the plea deal, the federal investigation and charges in New York, and Epstein’s “suicide.” Now, I put that term in quotation marks because the final episode also goes into some depth regarding the potential that Epstein’s death was not a suicide at all.

Remember all the memes I mentioned earlier? The series discusses various conspiracy theories related to the high-powered individuals Epstein held as company and the possibility that these people of influence would not want to leave any chance that Epstein might incriminate them, as well.

Epstein’s representatives went so far as to hire a celebrity forensic pathologist, Michael Baden, to review and independently observe Epstein’s autopsy.

Baden found evidence—in the form of the ligature mark and fractures of the Adam’s apple and hyoid bone in the neck—that the autopsy pointed more toward homicidal strangulation as opposed to death by suicide. Regardless of the cause of death, though, the survivors of Epstein’s criminal activity felt robbed of their chance at retribution.

Personal experiences with client suicide

Nevertheless, Epstein was far from the first, or last, criminal defendant to end their own life. As the Epstein case shows, some instances are more open to interpretation than others.

I still remember one client from many years ago who overdosed on a cocktail of different drugs. He was one of my favorite clients, a young man full of vigor and disdain for the system but still smart enough to listen to my advice and help me build his defense.

We were facing state drug trafficking charges. Everything seemed to be going fine; however, he was soon investigated by the feds in another jurisdiction, and his demeanor seemed to change. I didn’t hear from him as much, and he started to sound defeated when we would talk on the phone. His overdose came right before he was indicted, and I still find it hard to believe that it happened.

With other criminal defendants, though, sometimes the cause (or intention) of death is pretty straightforward. I once represented a defendant charged with double-digit counts involving sex crimes against minors. I have handled many of these cases over the years. However, in that particular circumstance, I found myself at odds with the client and his family.

We were not on bad terms by any means, but they could not pay the trial fee we had contracted to fight the allegations before a jury. I tried to work with the family, but they simply couldn’t (or maybe just wouldn’t) pay any of the trial fee at all.

Consequently, I had to withdraw as counsel. The allegations concerned multiple accusers, and they spanned multiple counties. It was not a case I could try pro bono, and I knew there would be a substantial commitment on the part of myself and my staff.

The judge ordered the defendant to get new counsel before his pretrial hearings, but he never did. He had multiple attempts to obtain new counsel, but he never hired anyone. On the morning of his last date to show up with an attorney, I found out that he shot himself and died as a result.

Image from Shutterstock.com.

The first example was tough to swallow, as I liked the client, and I felt that we had some angles to work on potential suppression of evidence. We had discussed that, and I thought I had given him some realistic hope.

However, I was also able to synthesize that, as with most drug overdoses, there was a real possibility that the death was not intentional, regardless of the timing and context. As a result, I was able to process the grief and move past it to a degree.

That last one stuck with me for a while and still bothers me to this day. Honestly, it’s hard not to think that I played some role in the hopelessness that had led to his suicide. After all, I was the attorney who withdrew from his case when he couldn’t pay anything toward the trial fee that we had negotiated. It was difficult imagining a reality in which I had stayed on as counsel, we had proceeded to trial, and the defendant was still alive—regardless of the jury verdict.

Still, in that alternative reality, I wonder how painful the experience would be if the defendant shot himself on the eve of trial or during the trial itself. I’ve never had that happen, but I can imagine it would be extremely traumatic for any attorney.

I also have to remind myself that I know there are attorneys he could have hired, regardless of his price point. At the end of the day, I’ve tried to realize some people are sadly going to take their own lives, no matter the circumstances. It’s a tough world, and that’s why no one ever makes it out alive.

Adam Banner

Adam R. Banner is the founder and lead attorney at the Oklahoma Legal Group, a criminal defense law firm in Oklahoma City. His practice focuses solely on state and federal criminal defense. He represents the accused against allegations of sex crimes, violent crimes, drug crimes and white collar crimes.

The study of law isn’t for everyone, yet its practice and procedure seems to permeate pop culture at an increasing rate. This column is about the intersection of law and pop culture in an attempt to separate the real from the ridiculous.