It's Both the Roberts and Kennedy Court, Supreme Court Experts Say

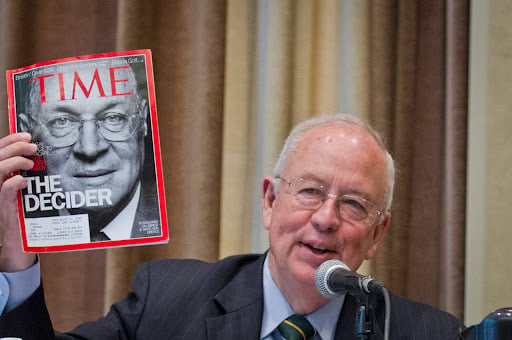

Kenneth Starr with a copy of Time magazine featuring

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy on the cover.

©Kathy Anderson 2012

The June 18 edition of Time magazine features a cover photo of U.S. Supreme Court Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, proclaiming him “The Decider.”

Flick forward a month to the July 16 edition, and you’ll see a a cover shot of Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. “Roberts Rules,” the headline says.

So whose court is it? Frankly, it’s both, and for exactly those reasons. “Time magazine has it right in both respects,” said Kenneth Starr, the former solicitor general and federal appellate judge who is now president of Baylor University.

Chief Justice Roberts may rule—especially by casting the key vote in last term’s major case on the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act—but Justice Kennedy still exercises his powers as the court’s most important persuader.

“He is clearly at the center,” Starr said of Kennedy at yesterday’s seminar, “The Roberts Court Year Six: Is It Still the Kennedy Court?” Joining Starr on the panel were constitutional law professors Pamela Karlan of Stanford University and Columbia University’s Jamal Greene.

While Kennedy joined the majority in 93 percent of the court’s cases last term, Roberts came in a close second, with 92 percent, Starr said.

Pamela Karlan. ©Kathy Anderson 2012

But Kennedy has become a different kind of swing vote than his predecessor, retired Justice Sandra Day O’Connor. “She was more of an incremental, cut-the-baby-in-half kind of justice,” Karlan said. O’Connor “would have said, ‘This is really close. Let’s devise a formula.’ ”

But Kennedy “is not such a baby-cutter,” Karlan added. “He would get emotional.”

Said Starr: “He’s a pragmatist. He finds out what works and avoids formalism.”

Yet Roberts took control in the Affordable Care Act cases, especially seeking to prevent the court from becoming submerged in the same kind of stormy political seas drowning Congress and the presidency. His decision upholding the statute was “designed so that the court did not look like another body fighting across the aisles,” as Congress has, Karlan said.

Jamal Greene. ©Kathy Anderson 2012

“It was [Roberts’] low-cost way of signaling solidarity,” Greene said. The chief justice “is a student of history. The last time the court struck down a congressional law as significant was probably the Missouri Compromise in Dred Scott.”

“The hyperpolarization of policy found its way on to the court,” Karlan added. “It was coming to be viewed as just another branch of government with policy like the others. They need not be politicians in robes, so they had to get above politics.”

Starr suggested that had Roberts taken the seat held by O’Connor, “he would have said, the heck with it all,” and likely joined the ACA case’s dissent. But becoming chief justice, and taking the seat of Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist—for whom Roberts clerked—put him in a more profound role.

In addition to Rehnquist, Roberts also has “taken a page from Chief Justice John Marshall, who was protective of the dignity of the court during turbulent times” in the early 1800s.

In the end, Greene said, the term featured good news and bad news. “The good news was that the votes could have been more decisive,” with the court backing away from more hard-core politicking.

The bad news, Greene added, “were the leaks that came out at the end of the term, saying that there was spitball-throwing” when justices in the ACA minority were supposedly incensed at Chief Justice Roberts for joining the majority.

“It again calls on the chief justice’s leadership” to limit the politics, Greene said.