How losing RBG could shape criminal justice for years to come

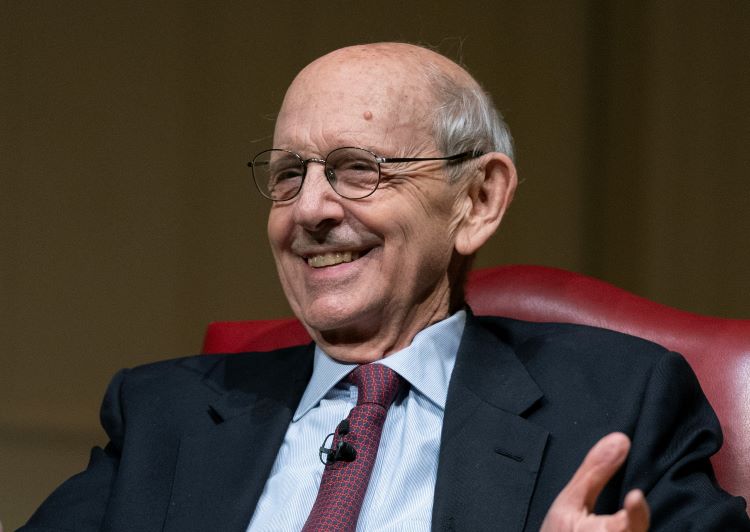

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Photo from Shutterstock.com.

In the wake of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death, a newly reconfigured Supreme Court is expected to consider a raft of hot-button issues from Obamacare to abortion. But it is also set to hear several less widely anticipated criminal justice cases dealing with police accountability, juveniles sentenced to life behind bars and other key issues.

It’s unclear whether the current eight-justice court will rule on these cases—in the event of a 4-4 tie, a lower court’s ruling would stand—or whether President Trump’s (likely very conservative) nominee for Ginsburg’s seat will play a critical role in deciding them.

Below, a roundup of the criminal justice questions the high court is already scheduled to consider this fall, as well as ones that it may take up in coming terms:

If the cops don’t catch you, do you still have rights?

In the upcoming case Torres v. Madrid, which is scheduled to be argued before the Supreme Court on Oct. 14, the question at hand is whether police must succeed at detaining someone in order for the person to be entitled to the constitutional rights that come with being detained.

Confused? Here’s an example from the case: In 2014, two police officers approached Roxanne Torres, who was sitting in her car. It was dark, and she said she thought they were trying to rob her, so she drove off. They shot into the vehicle, injuring her, but she got away.

Torres later filed a civil rights lawsuit against the officers, saying they had used excessive force against her. But a federal court ruled that because they had not actually detained her, she did not have a constitutional right against “unreasonable search and seizure.”

In other words, only if cops have made contact with you—and you submit in some way, which the court has yet to clearly define—do they need probable cause to continue to subdue and detain you. But if they haven’t caught you yet, none of this applies.

Especially with the court leaning in a more tough-on-crime direction without Ginsburg, this logic will likely be upheld, says Lee Kovarsky, a professor at the University of Texas School of Law and an expert on the Supreme Court and Fourth Amendment rights.

Should children sentenced to life in prison without parole get a second chance?

In its landmark 2016 decision Montgomery v. Louisiana, the Supreme Court said that prisoners originally sentenced to life behind bars when they were children deserve an opportunity to prove that their crime resulted from their immaturity—in other words, that they are not irreparably evil. And if they can show this, they should be given a new, shorter sentence and a second chance at life outside of prison.

But that ruling has been interpreted in a whole host of ways in courts across the country. Many judges and prosecutors have claimed to adhere to the Montgomery ruling while simply re-sentencing these formerly juvenile prisoners to a lifetime of confinement all over again, without ever issuing a formal ruling on whether they have been rehabilitated.

The upcoming case Jones v. Mississippi, to be argued before the high court on Nov. 3, is all about what steps a court must take to show that it has seriously considered the question of youth rehabilitation. The defendant, Brett Jones, who was abused as a child and committed a murder at age 15 during a domestic dispute, has since expressed deep remorse and become educated and religious, according to testimony by corrections officials.

He will argue that a judge can’t simply note his rehabilitation before re-sentencing him to life in prison. Rather, the judge must specifically rule on whether or not he is permanently incapable of positive change.

But according to legal experts, as well as youth advocates at the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth, the death of Ginsburg and the addition of conservative justices Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and potentially another Trump appointee, could reverse the Supreme Court’s long-standing liberal approach to questions of how children convicted of crimes can grow and change. (Even a 4-4 split, should a new judge not yet be confirmed, would result in Jones losing his case against the state of Mississippi.)

Should immigrants convicted of minor crimes be deported?

In the case of Pereida v. Barr, an undocumented Mexican man named Clemente Avelino Pereida, who has now been in the United States for 25 years, attempted to get a job in Nebraska by using a fake Social Security card. He was not sentenced to any jail time for this misdemeanor.

But the Department of Homeland Security tried to deport Pereida based on his crime. Under federal law, he could only fight back against the deportation order if the offense did not involve “moral turpitude,” a term that Congress and the courts have never clearly defined.

The question now before the Supreme Court is who should have to prove whether the crime in question was morally significant enough to merit removal from the United States: the person about to be deported or the government?

“It’s a seemingly technical issue of immigration law but it actually affects thousands of people every year,” said César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández, a law professor at the University of Denver and an expert on the nexus between immigration and criminal law.

García Hernández says the most common type of case is when ICE detains an immigrant who has been here for years or even decades, who faced a low-level drug charge in the distant past. Records of the criminal case may never have been made, or may have been destroyed, or otherwise may be difficult or impossible for the person to obtain. That means he or she will have trouble proving it was just an arrest for possession of a single joint, for example, in order to argue that it was not a crime of moral turpitude.

The immediate consequence of losing Ginsburg is that the case may end up in a 4-4 split, experts say. Lower court decisions would prevail, and more immigrants convicted of minor offenses in many parts of the country would be deported.

Issues that may come before the court soon:

Do incarcerated people have a right to be protected from the pandemic?

Given the crowded indoor conditions, limited access to cleaning supplies and notoriously poor health care, people in prisons and jails have faced a devastating toll from COVID-19, with infections and death rates in more than a dozen state prison systems and in the federal system outpacing the general population. In recent months, prisoners around the country have brought lawsuits arguing that states and counties have violated their constitutional rights “by failing to provide them with reasonably safe living conditions as the pandemic rages,” according to one ruling.

The bar is high for prisoners to prevail in cases like this, and generally “courts are reluctant, in a time of crisis, to tell officials how to behave,” says Margo Schlanger, a University of Michigan law professor and an expert on prisoners’ rights litigation. “It makes them a little anxious to tell sheriffs and [corrections departments] to do things that are very hard to do.” But the issue is pressing enough—and there are enough of these cases—that Schlanger says she’s watching closely to see if the high court gets involved.

However, given its ideological fault lines even before Ginsburg’s death, if the Supreme Court does step in, it may be to give jailers even more flexibility to manage the pandemic.

This has already happened once: When a federal judge in California ordered the Orange County Jail to take some basic precautions to prevent the spread of COVID-19, the court voted to undo the order and allow jail officials to decide how to handle the virus. The four liberal justices—including Ginsburg—dissented.

Should police officers be shielded from the consequences of their misconduct?

The national spotlight on police misconduct and brutality has made a previously obscure legal doctrine into the stuff of kitchen table conversations. Qualified immunity, its critics argue, allows police to literally get away with murder. And court-watchers say that if Congress doesn’t act to reform it, the Supreme Court may well do so.

Police have Tased a pregnant woman who refused to sign a traffic ticket; stolen over $225,000 worth of property; destroyed a woman’s empty house with tear gas grenades, rendering her homeless; and forced a man to live, naked, in a cell in which every surface was covered with “massive amounts” of feces, for six days. In all of those cases—and many more—judges have found that the officers clearly behaved unethically, and, in some cases, illegally, but they could not be sued for wrongdoing because it was not “clearly established” by past cases that their actions violated the person’s rights.

Last term, critics of qualified immunity were confident the Supreme Court was going to reconsider it when the justices seemed to express a serious interest in several cases challenging the doctrine. But they ultimately declined to do so. “The court was obviously aware that after George Floyd, police reform was getting a lot of attention in Congress,” said Jay Schweikert, a policy analyst with the conservative-leaning Cato Institute’s project on criminal justice. “They may have thought, ‘Thank God Congress can fix this for us.’ If the court can avoid deciding difficult questions, it often takes that opportunity.

”If Congress does not act, watch for whether the Supreme Court takes this up. In a widely discussed decision this summer, a federal judge in Mississippi all but dared the court to ignore the issue. District Judge Carlton Reeves granted qualified immunity to a police officer while lambasting the legal precedent he said forced him to do so.

This is one area where Ginsburg’s absence might not torpedo chances for reform. When the court declined to take up the qualified immunity cases last term, the only justice who wanted to pursue the issue was Clarence Thomas; the Constitution does not shield public officials from being sued, so originalists like Thomas are skeptical of what they see as a judge-invented rule. And liberals such as Sonia Sotomayor—who along with Ginsberg dissented in a closely watched 2018 case—tend to agree from a perspective of seeking police accountability. “I don’t think it’s one of the issues that would have led to a traditional 5-4 split,” Schweikert said.

This article was originally published by the Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization covering the U.S. criminal justice system. Sign up for the newsletter, or follow the Marshall Project on Facebook or Twitter.