Financial fraud enforcer rips crypto culture for letting compliance slide

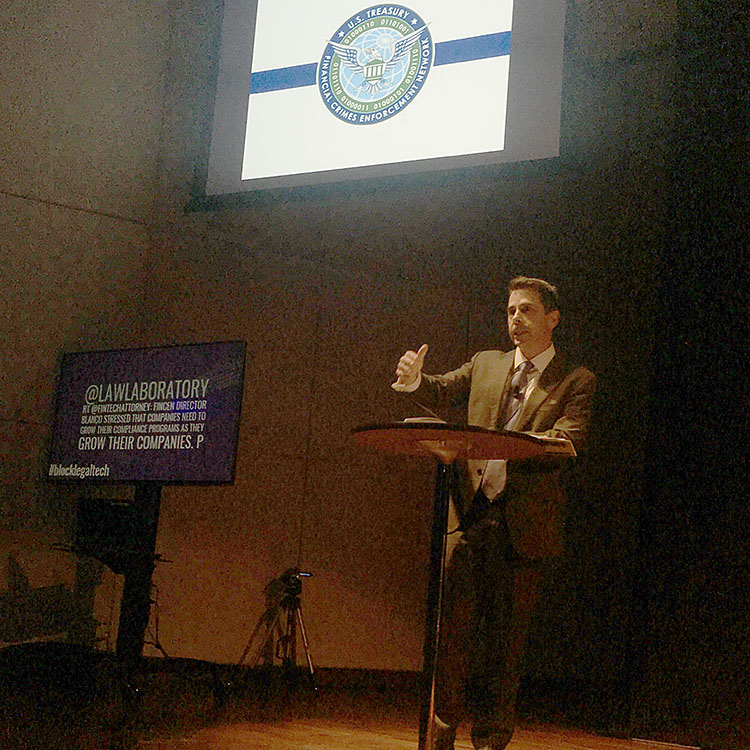

Kenneth A. Blanco, director of the U.S. Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, addresses a blockchain conference Aug. 9 at Chicago-Kent College of Law. ABA Journal/Stephen Rynkiewicz.

Financial crimes enforcers are watching cryptocurrency practitioners—and they don’t like what they see.

The Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network and the Internal Revenue Service “have examined over 30 percent of all registered virtual currency exchangers and administrators since 2014,” said Kenneth A. Blanco, FinCEN’s director, in an Aug. 9 speech to the Block (Legal) Tech conference at Chicago-Kent College of Law. “And there is no question we have noticed some compliance shortcomings.”

Specifically, Blanco maintains that adequate money laundering controls are not put in place until a trading platform or peer-to-peer exchanger gets an investigation notice.

“Let this message go out clearly today: This does not constitute compliance,” he said. “Compliance does not begin because you may get caught, or because you are about to be discovered. That is not a culture that protects our national security, our country, and our families. It is not a culture we will tolerate.”

The government receives more than 1,500 suspicious activity reports a month involving virtual currency, Blanco said. In levying a $110 million fine last year against the online currency exchange BTC-e, Blanco said, the reports gave investigators information on exchange activities and beneficial owners, along with jurisdiction and banking leads.

Noting the role of cryptocurrencies in the illicit opioid trade, Blanco went beyond his prepared remarks to urge compliance with reporting on currency transactions. “All you have to do, folks, is talk to a father or a mother who lost a child to opioids,” he said, “so that you understand how important it is that this information get out to us. And all of you are the first lines of defense.”

Fielding audience questions, Blanco questioned the argument of Bitcoin and other crypto proponents that blockchain transactions are open and therefore less risky.

“How many of you think they actually see everything on a blockchain?” Blanco said. “Let’s not kid ourselves. Being a lawyer, words matter. The meaning of those words matter and the consequences of those words matter. So when we say that everything is on the blockchain, I’m not so sure that’s true.”

The Treasury enforcer noted that foreign operations have U.S. reporting obligations. Cryptocurrency businesses may have to register with multiple agencies, including state regulators, the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission.

Jess Cheng of the International Monetary Fund (left) and Amy Hartman of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. ABA Journal/Stephen Rynkiewicz.

The remarks echoed those of Amy Hartman, assistant director of the SEC’s cyber unit. Hartman cited the opportunities for fraud posed by virtual currencies that span international borders. Hartman advised companies planning an initial coin offering to “engage competent securities counsel” on registration requirements, even if they’re not U.S. based.

“When you’re making that consideration it’s not sufficient to say, well, we don’t intend to offer it to U.S. investors,” Hartman said. “If you hear from us, we’re going to say, what steps did you take to insure that U.S. investors cannot be part of this offering?”

Jess Cheng, International Monetary Fund counsel, also noted that the speed and efficiency of blockchain transactions creates new openings for bad actors.

“You can’t really say with a straight face that criminals haven’t benefitted from crypto assets,” Cheng said. “You don’t have to worry about shipping a duffel bag of cash. It’s as easy to transfer crypto assets to the other side of the world as it could be sending crypto assets to the person sitting next to you.”