Federal judge rules Florida can't require payment of fees before ex-felons can vote

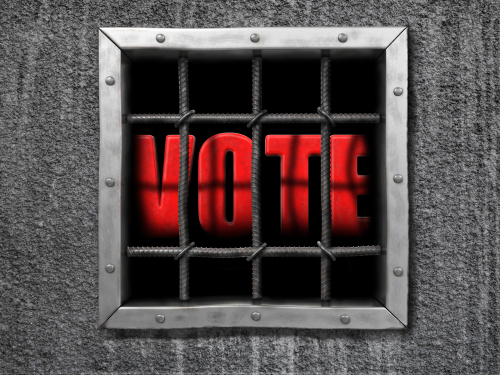

Image from Shutterstock.com.

A federal judge ruled Sunday that it is unconstitutional in some circumstances for Florida to require felons who have completed their sentences to pay legal financial obligations before being allowed to vote.

U.S. District Judge Robert Hinkle of Tallahassee said requiring payment is unconstitutional if the felons can’t afford to pay or if the financial obligation is a fee or fine that was imposed to fund the criminal justice system.

Hinkle’s ruling affects hundreds of thousands of people with past felony convictions in Florida, according to press releases by the American Civil Liberties Union and the Brennan Center for Justice. The New York Times, the Washington Post and the Tampa Bay Times have coverage.

Hinkle ruled after the Atlanta-based 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals found in February that the fees-and-fines requirement would violate the equal protection clause as applied to the indigent plaintiffs who filed suit. The 11th Circuit ruling upheld Hinkle’s preliminary injunction allowing the case plaintiffs to vote.

Hinkle’s Sunday ruling cited the equal protection violation for those unable to pay. He also found a violation of the 24th Amendment’s ban on poll taxes or other taxes as a condition for voting.

Restitution and criminal fines are not taxes, and the 24th Amendment allows Florida to require payment of those obligations before voting, Hinkle said. But fees and fines that are imposed to help fund the criminal justice system do amount to a tax, and former felons can’t be banned from voting for failure to pay them, Hinkle said.

Florida voters had restored voting rights to many former felons in 2018 by approving Amendment 4. The ballot initiative restored voting rights “upon completion of all terms of sentence including parole or probation.”

The Florida legislature passed a bill in May 2019 that barred former felons from registering to vote if they had failed to pay all of their legal financial obligations stemming from the felony conviction. The bill was signed into law in June 2019.

Hinkle’s order pointed out that many felons don’t know the amount of their unpaid legal financial obligations, and some have no way to find out the amount.

In many counties, felons can learn the amount by obtaining a copy of the judgment, but there is often a fee to obtain it. And if a would-be voter does obtain the judgment, it may be difficult to ascertain which of the fees and fines apply to the felony conviction. It is also difficult to learn how much has been paid toward the outstanding amount.

To remedy that problem, Hinkle required the state to provide advisory opinions upon request to felons who are unsure of their eligibility to vote. The opinions would set out the amount of unpaid obligations and determine ability to pay.

An assertion that a person is able to pay will have no effect in four instances, Hinkle said.

The first is when the would-be voter had an appointed lawyer or was granted indigent status in the case that resulted in a felony conviction. The second is when the person submits an affidavit establishing indigency. The third is when the outstanding financial obligations have been converted to civil liens. The fourth is when voting authorities have credible and reliable information that the would-be voter is unable to pay.

If the advisory opinion is not provided in 21 days, the former felons can go forward with registration and voting, Hinkle said.

Hinkle ruled after trying five consolidated cases by videoconference. The plaintiffs were the American Civil Liberties Union; the ACLU of Florida; the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU Law; the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund; the Campaign Legal Center; the Southern Poverty Law Center; and the law firm Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.