Does 'Making a Murderer Part 2' live up to its predecessor?

Steven Avery’s attorney Kathleen Zellner addresses a crowd of reporters in Making a Murderer Part 2. Photos courtesy of Netflix.

Back in 2015, my wife and I were on vacation looking for something to watch while we fell asleep. She’d heard good things about the newly released Netflix series Making a Murderer and thought it would be great fodder for slumber. We both imagined a dull documentary with a steady voice that could lull the mind and shut down the eyes.

We decided to give the first episode a try. Instead of lulling us to sleep, it was riveting. We finished the entire series before returning home.

Making a Murderer took the country by storm. It permeated social media. Everyone had their own opinion for better or worse. Coworkers were discussing it. People would ask me about it when they learned I’m a criminal defense attorney. For whatever reason, it struck a chord with the general viewing audience. Consequently, it was only a matter of time before the series’ success was extended.

THE BACKGROUND

For those unfamiliar with the original Making a Murderer (let’s refer to it as “season one”), the series follows Steven Avery and his (at the time) 16-year-old nephew Brendan Dassey as they fight to prove their innocence. Both were charged with the murder of 25-year-old Teresa Halbach. Both were tried by jury. Both were convicted and given life sentences.

At the heart of the documentary is the claim that Avery was railroaded by law enforcement officers and prosecutors seeking to end a vendetta … a vendetta involving Avery’s $36 million wrongful-conviction lawsuit against Manitowoc County, the sheriff whose office arrested him, and the county district attorney who prosecuted him.

Some believe Avery is “guilty as hell”—others argue that new evidence will lead a judge to vacate his sentence. But, no matter which side of the fence you stand on, it’s obvious the prosecution and law enforcement didn’t handle things in a manner necessary to achieve a rock-solid conviction.

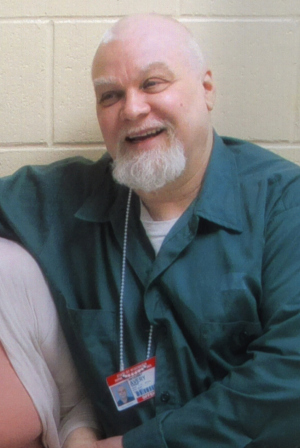

Steven Avery

Steven AveryBut first, let’s get one thing clear: Steven Avery is no angel. When he was 18 years old, he was convicted of burglary. By the age of 20, he was convicted again—this time for animal cruelty after he poured gasoline on a cat and threw it into a fire.

When he was 23, he was convicted of endangering the safety of another person after he ran his cousin off the road at gunpoint. His cousin, the wife of a Manitowoc County sheriff’s deputy, says the incident was retaliation for her reporting that Avery exposed himself to her. In that case, he was sentenced to six years in prison.

In 1985, the same year he was convicted of assaulting his cousin, Avery was convicted of false imprisonment, first degree sexual assault, and attempted murder in the kidnapping and rape of Penny Beernsten. Beernsten was forcibly raped while jogging near her home, and she identified Avery as her attacker in a police lineup. Avery, who maintained his innocence, was convicted and sentenced to 32 years in prison.

His protestations of innocence caught the attention of the Wisconsin Innocence Project, who intervened on his behalf. Some 18 years after he went to prison for Beernsten’s assault, Avery was exonerated by DNA evidence—evidence matched to Gregory Allen, a man serving 60 months in prison for another sexual assault that occurred after Beernsten was attacked. The Innocence Project noted Allen bore a “striking resemblance” to Avery.

After he was exonerated, Beernsten says Avery contacted her asking for money. He also filed that $36 million lawsuit against the county.

Only days after the first deposition in the lawsuit, Avery was arrested again—this time for the murder of Teresa Halbach, a photographer whose car and charred remains were found at the salvage yard owned by the Avery family. Teresa Halbach had disappeared on October 31, 2005, after being scheduled to meet Avery at the salvage yard to take pictures of a minivan for sale in Auto Trader Magazine.

Again, Avery claimed his innocence, and his supporters were left wondering if wrongful-conviction lightning could strike twice in the same place. However, his young nephew Brendan Dassey confessed to the murder while also inculpating Avery during an interrogation. As one can imagine, the “confession” went a long way towards the ultimate convictions. The two have been appealing those convictions ever since.

Enter the recently released Making a Murderer Part 2.

A PLAYBOOK FOR POST-CONVICTION PRACTICE

Because Dassey and Avery were convicted in season one, the second season naturally focuses on the appellate processes they pursue. Detailed explanations are given for the method and means both employ to attack their convictions. Not only are the procedures explained at length, but rules, requirements, burdens, and precedent are fully explored in surprising depth.

When Making a Murderer Part 2 begins, both Dassey and Avery have new counsel. Laura Nirider and her co-counsel work to overturn Dassey’s conviction through federal habeas corpus. Dassey’s attorneys are fighting to show his confession was involuntary. They argue his statements were coerced in violation of his 5th Amendment rights. They also claim he was deprived of his 6th Amendment right to effective counsel due to his pretrial attorney’s antics.

Avery, on the other hand, is represented by Kathleen Zellner. Zellner has the distinction of assisting 17 inmates in overturning their convictions (that’s more than any other private attorney in the US). She takes Avery’s case pro bono and begins to work her way towards filing his state-level post-conviction petition (you can view documents in the case here).

For those interested in the innerworkings of the appellate landscape, the distinctions between the two defendants’ procedural postures is intriguing. I was extremely impressed by the depth of the discussions regarding the interplay between state and federal court systems. I was equally surprised by the step-by-step explanations of the paths these attacks must follow.

Still, it’s possible my interest stems from a close connection to the content. I try criminal cases to juries. I do appellate work. So obviously, I have an interest in these topics, and I appreciate the descriptive detail the documentary delivers. Others who are unfamiliar with the area of law will either be happily informed or bogged-down by the density of the subject matter.

Brendan Dassey (center) and his mother, Barb Tadych, and step-father, Scott Tadych.

Brendan Dassey (center) and his mother, Barb Tadych, and step-father, Scott Tadych.

Admittedly though, Dassey’s habeas corpus sections move much more slowly than Avery’s pursuit of post-conviction relief. In the habeas portions, the audience is mostly limited to a somewhat repetitive narrative revolving around the involuntary nature of Dassey’s confession. And because the case is at the habeas level, there are no surprise discoveries—the federal judges are only interested in whether the evidence in the record reflects a violation of Dassey’s constitutional rights.

The segments involving Avery’s post-conviction process are a bit livelier. Part of that is due to Zellner’s powerful presence. Since she is representing Avery at the state-court level, she is still in the process of gathering new evidence to supplement the record. This process gives her and her team the opportunity to pick the prosecution’s case apart piece by piece using some of the top experts and techniques available. Throughout the 10-episode season, she utilizes bloodstain analysis, accident reconstruction, forensic testing, and even “brain fingerprinting” to bolster her claim that Avery is innocent of the charges.

THE FUTURE OF THE FRANCHISE

With its focus on the appellate system, Making a Murderer Part 2 ultimately runs the risk of boring those fans who reveled in the suspense of season one’s jury trial settings. It makes sense. The appellate process is not glamorous. It’s not sexy. As the documentary notes, there often aren’t deadlines for judges to decide post-conviction issues and subsequent appeals. It is a long, drawn-out process that moves at a snail’s pace in most instances.

The most recent season drags on to a certain extent simply because the creative team made the decision to delve into the specifics of a very specialized area of law—one that many practicing attorneys are even confused by. Post-conviction cases are difficult. Making a Murderer Part 2 gives an extensive and thorough treatment to each appellate procedure employed by the attorneys.

However, there aren’t a ton of new developments or “Aha!” moments, and at times it feels like the series is simply employing filler in order to reach ten episodes again—even though there was plenty of subject matter to work with. Dassey’s coerced confession is one example. I’ve written about false confessions in my column before. It’s an interesting phenomenon, and the topic as a whole could have been explored in more detail.

Regardless of the slower pace and sometimes dense subject matter, there are still plenty of interesting aspects that differentiate this season from its predecessor. Most of that is attributed to Zellner. The length to which she and her team go to discover new evidence and reassess that which already exists is impressive. Few attorneys have the resources to front the funds on a pro bono basis. Sadly, very few defendants have the funds to devote to experts as well.

According to Zellner, the claims she made on behalf of Avery have led to an open investigation. She plans on filing Avery’s newest appeal on December 20, 2018.

Only time will tell the fate of Brendan Dassey and Steven Avery. However, even if both convictions are ultimately vacated, that does not necessarily mean Dassey and Avery are innocent…nor does it mean they will go free. It is quite possible that they are both the victims of a miscarriage of justice and the perpetrators of a horrible crime.

Hindsight is 20/20, and Making a Murderer Part 2 gives the prosecution and those who stand by Avery’s guilt the ability to criticize and critique season one. As is the case with many true crime documentaries, there are allegations the directors left out information that was damning to Dassey and Avery’s claims of innocence. With this series (and every other participant in the genre), one has to wonder how much artistic liberty is taken with the facts and circumstances of the underlying case. As David Harsanyi wrote in The Federalist subsequent to season one:

“I was convinced the criminal justice system and Manitowoc County were likely corrupt, and that many people in that office wanted to see Avery end up back in jail. I was convinced that I was being manipulated by directors Laura Ricciardi and Moira Demos. … I was definitely convinced that Avery was guilty of the murder. And, believe it or not, a viewer could believe all those things simultaneously.”

Regardless, the right to a fair trial is a constitutional right. When misconduct arises, it must be exposed. However, as Making a Murderer Part 2 makes painfully clear, exposing these issues is not the end-all. It’s just the beginning.

Adam Banner

Adam R. Banner is the founder and lead attorney at The Law Offices of Adam R. Banner, a criminal defense law firm in Oklahoma City. His practice focuses solely on state and federal criminal defense. He represents the accused against allegations of sex crimes, violent crimes, drug crimes and white collar crimes.

The study of law isn’t for everyone, yet its practice and procedure seems to permeate pop culture at an increasing rate. This column is about the intersection of law and pop culture in an attempt to separate the real from the ridiculous.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.