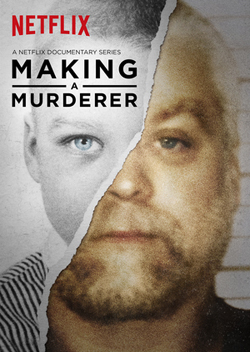

Conviction tossed for one 'Making a Murderer' suspect; lawyer's conduct 'inexcusable,' judge says

A federal magistrate judge is citing interrogators’ coercive techniques in overturning the conviction of a Wisconsin man convicted of helping his uncle kill a woman in a murder case examined in the “Making a Murderer” Netflix series.

U.S. Magistrate Judge William Duffin of Milwaukee overturned the conviction of Brendan Dassey on Friday and gave prosecutors 90 days to initiate proceedings to retry him, report the Chicago Tribune and the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. The opinion is here.

Duffin also said the conduct of Dassey’s initial defense lawyer, Leonard Kachinsky, was “inexcusable both tactically and ethically.” But Dassey’s lawyers had not pressed a claim of ineffective assistance on the initial appeal, Duffin said, and he could not overturn the conviction on that ground.

Dassey’s uncle, Steven Avery, was convicted of murder in the slaying of photographer Teresa Halbach. Dassey was convicted of homicide, second-degree sexual assault, and mutilation of a corpse. Avery had previously spent 18 years in prison after being wrongfully convicted of rape. Avery had a wrongful conviction case pending at the time of Halbach’s murder, and defense lawyers have argued evidence was planted in retaliation for the case.

Duffin said investigators had disclosed unknown facts and used leading questions in their questioning of Dassey. “It is clear how the investigators’ actions amounted to deceptive interrogation tactics that overbore Dassey’s free will,” Duffin said.

Repeated false promises made during interrogations of Dassey, “when considered in conjunction with all relevant factors, most especially Dassey’s age, intellectual deficits, and the absence of a supportive adult, rendered Dassey’s confession involuntary under the Fifth and 14th amendments,” Duffin wrote.

Investigators questioned 16-year-old Dassey after his cousin told police that he had recently lost 40 pounds and had been “acting up lately”—staring into space and crying uncontrollably.

Investigators told Dassey they were on his side and already knew details of the crime, but wanted information from him. “I will not [leave] you high and dry,” one investigator said. “I’ll stand behind you.” When the investigators asked Dassey what was bothering him, he said, “Trying to find a girlfriend.”

Duffin discussed the allegations against Kachinsky that were explored in a post-conviction hearing. According to Duffin, Kachinsky “was excited to be involved in Dassey’s case because by then it had garnered significant local and national attention.”

Dassey told Kachinsky that the allegations against him weren’t true and he wanted to take a lie detector to prove his innocence, Duffin said. Kachinsky told local media, however, that Dassey was sad, remorseful and overwhelmed, and he blamed Avery for leading him down the criminal path, according the media accounts. He also said a plea deal had not been ruled out.

Kachinsky later said he spoke with the media to get Dassey and his family accustomed to the idea of a plea deal. On the Nancy Grace TV show, Kachinsky said that if Dassey’s recorded statement was accurate and admissible, “there is, quite frankly, no defense.” He also referred to interrogators’ techniques as “pretty standard” and “quite legitimate.”

“Over the roughly three weeks following his appointment,” Duffin wrote, “Kachinsky spent about one hour with Dassey and at least 10 hours communicating with the press.” The results of the polygraph were inclusive, yet the examiner referred to Dassey as “a kid without a conscience,” or something similar. Kachinsky did file a motion to suppress the confession, but it was denied. He also hired the polygraph examiner as an investigator, and the examiner falsely told Dassey that his polygraph indicated deception. The examiner questioned Dassey again, telling him he couldn’t help him unless he was sorry.

The examiner told Kachinsky he believed Dassey was on board with a plea deal. Kachinsky allowed state investigators to question Dassey without his presence, drawing a letter of protest from the state public defender. The trial court removed Kachinsky as Dassey’s lawyer.

“Although it probably does not need to be stated, it will be: Kachinsky’s conduct was inexcusable both tactically and ethically,” Duffin wrote. “It is one thing for an attorney to point out to a client how deep of a hole the client is in. But to assist the prosecution in digging that hole deeper is an affront to the principles of justice that underlie a defense attorney’s vital role in the adversarial system. “

On appeal, lawyers for Dassey had argued Kachinsky had a conflict of interest, rather than arguing his representation violated the right to effective counsel. As a result, Duffin said, he could not reconstrue Dassey’s claim as a claim for ineffective counsel.

The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel interviewed Kachinsky in January. The newspaper said Kachinsky was semiretired and battling leukemia “and doesn’t seem to want to expend what time and energy he has left responding to his now many critics.”

He told the newspaper he considered suing Making a Murderer for slander, “but those suits tend to eat up time and put money in lawyers’ pockets.” He also said he agreed to take additional training and to meet other conditions for a year as an alternative to discipline stemming from the case.

Kachinsky issued a statement on the overturned conviction, Bustle reports in a story noted by Above the Law.

“Magistrate Judge Duffin reversed Dassey’s conviction on the suppression issue I litigated before leaving the case,” Kachinsky said. “I preserved that issue for appeal so that his future attorneys might raise it like they did. Even though Dassey and I parted ways on how he should proceed, I did my job and enabled Dassey’s future attorneys to do theirs. The next step will probably be up to the 7th Circuit as the state will likely appeal.”

Updated on Aug. 16 to include statement by Kachinsky.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.