Clemency project recipient gets a smartphone—and hope

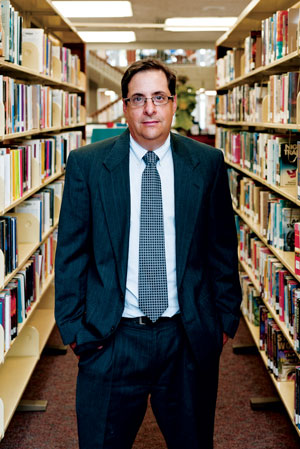

James Ledford. Photo illustration by Wayne Slezak

James Ledford got his first smartphone in June. It has a bit of a learning curve.

“Everybody in society, they kind of evolved into this technology,” says Ledford, who left prison in late June. “It was just thrown in my hand ten days ago, you know?”

After 15 years in federal prison, there’s a lot that Ledford, 48, is catching up with. Ledford is one of the hundreds of beneficiaries of the Clemency Project 2014, the Obama administration’s attempt to commute long federal sentences handed down to nonviolent drug offenders. As part of the CP14, as it’s known, the government solicited pro bono help for the prisoners from attorneys around the nation. The ABA’s Criminal Justice Section was one of five legal organizations that helped organize that pro bono effort. Ledford was the subject of the ABA Journal’s story on CP14, published in July of 2015.

Ledford was released to a halfway house in Tampa, Florida, in late June. He says life in the halfway house is busy: He has responsibilities around the house itself; group and individual counseling; meetings with a case manager. He’s in the process of looking for a job, and he recently had his driver’s license reinstated. He’s also had to get passes to leave the halfway house for a few essentials he didn’t have when he left prison, like clothes.

And he’s reacquainting himself with life on the outside. The smartphone may be unfamiliar, but Ledford says he loves it.

“I’m in touch with my family. I’ve got pictures of my grandchildren on there,” he says. “The Google thing is really nice.”

He’s already used Google to learn more about some of the jobs he’s applying for. And he wants to get back in touch with some more distant relatives he couldn’t keep up with on the inside. His immediate family came and met him on the day he was released from prison, which he says was fantastic and surreal.

“I didn’t know if I was ever going to get to hug [my father] again, you know, outside of a prison fence,” Ledford says.

Ledford expects to be at the halfway house, or possibly on home confinement, until April of 2019. After that, he hopes to move in with his brother’s family in Alabama and work with his brother in the railroad industry. (He had an auto shop with his father before addiction and prison, but he says the technology passed him by during his time in prison.)

Adam Allen, assistant federal public defender. ABA file photo by Alicia Katherine Johnson.

For years, Ledford was not expecting to be released at all. He received a life sentence in 2003 for possession of methamphetamine with intent to distribute. He told the ABA Journal in 2015 that he was an addict in 2003, selling “enough drugs to stay high.” He had four prior convictions, all related to drugs in some way, when he was pulled over in Lake Alfred, Florida with a pound of meth in his trunk. He immediately claimed the drugs, he says, in order to protect his wife from criminal charges. Ultimately, he pleaded guilty to a charge he knew carried a life sentence.

In prison, Ledford got clean and behaved so well that he was eventually put in the minimum-security part of the Florida prison complex where he served his time.

“I suspect a lot of people would be like ‘I got life in prison—what freaking difference does it make?’ But he’s really taken advantage of every possible opportunity in prison to improve himself,” Ledford’s former public defender, Adam Allen of the Middle District of Florida, told the ABA Journal in 2015.

When it came time to apply to CP14, he had help from Allen as well as CP14 organizer and former Criminal Justice Section co-chair James Felman. Nonetheless, a sentence commutation was not a sure thing. The Obama administration announced multiple clemency grants before the August 2016 announcement that included Ledford.

“I’m extremely gratified that the president granted his commutation,” Felman told the ABA Journal right after the announcement. “He was extremely deserving, and it’s very gratifying to be able to help someone get the relief they deserve.”

In all, CP14 helped 894 federal prisoners win sentence commutations, out of the 1,705 commutations granted during the Obama administration’s effort. It may have been the largest pro bono effort in American history.