Chemerinsky: Partisan gerrymandering has returned to the Supreme Court

Erwin Chemerinsky. Photo by Jim Block.

On Tuesday, the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments in what could be the two most important cases of the term—both involving the question of whether federal courts can hear challenges to partisan gerrymandering and, if so, when the practice violates the Constitution.

In Rucho v. Common Cause and Lamone v. Benisek, the court returns to one of the most significant issues confronting American democracy: Can the political party that controls the legislature draw election districts to maximize safe seats for itself?

Partisan gerrymandering is nothing new. In fact, the practice is named after Massachusetts Gov. Elbridge Gerry, who in 1812 signed a bill that redrew the state senate election districts to benefit his Democratic-Republican party. But what has changed are the sophisticated computer programs and other techniques that make partisan gerrymandering far more effective than ever before.

History in the making

In Davis v. Bandemer (1986), the high court held that federal courts could hear challenges to partisan gerrymandering. The court said that “the issue is one of representation, and we decline to hold that such claims are never justiciable.” The plurality opinion by Justice Byron White said for a group to prove a violation of equal protection, it must prove “both intentional discrimination against an identifiable political group and an actual discriminatory effect on that group.” The plurality concluded that “unconstitutional discrimination occurs only when the electoral system is arranged in a manner that will consistently degrade a voter’s or a group of voters’ influence on the political process as a whole.”

But the court gave a very fragmented opinion. Six justices found that challenges to gerrymandering are justiciable. Seven justices voted to uphold the districts used in Indiana, four by finding no constitutional violation and three by concluding that the case was not justiciable. Davis did not answer the question of what would be sufficient to prove that gerrymandering constitutes an effective denial to a minority of voters of a fair chance to influence the political process.

Eighteen years later, in Vieth v. Jubelirer (2004), the court effectively overruled Davis and dismissed a challenge to partisan gerrymandering as being a nonjusticiable political question. The plurality opinion, written by Justice Antonin Scalia, concluded that challenges to partisan gerrymandering are nonjusticiable political questions. Justice Scalia, joined by Chief Justice William Rehnquist and Justices Sandra Day O’Connor and Clarence Thomas, said there are no judicially discoverable or manageable standards and no basis for courts to decide when partisan gerrymandering offends the Constitution.

Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, concurring in the judgment, provided the fifth vote for the majority. He agreed to dismiss the case because of the lack of judicially discoverable or manageable standards. But he said that he thought such standards might be developed in the future. Thus, he disagreed with the majority opinion that challenges to partisan gerrymandering are always political questions. He said when standards are developed, such cases can be heard.

Two years after Vieth, in League of United Latin American Citizens v. Perry (2006), the Supreme Court again without a majority opinion refused to address the constitutionality of partisan gerrymandering—this time in Texas. Kennedy announced the judgment for the court and found that there was not sufficient evidence to show vote dilution. Scalia and Thomas would have dismissed on justiciability grounds, concluding that challenges to partisan gerrymandering inherently present a political question. Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. and Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. said the plaintiffs did not present a standard for determining when gerrymandering violates equal protection. They said they took no position as to whether a standard might be developed, but they agreed that the case should be dismissed as nonjusticiable for failure to state a claim.

Last term, the court had the opportunity in Gill v. Whitford to again consider whether federal courts may hear challenges to partisan gerrymandering and, if so, when it violates the Constitution. But the court found that the plaintiffs failed to prove they were personally injured and, thus, did not meet the requirement for standing to sue in federal court.

A three-judge federal court panel found that the partisan gerrymandering of the Wisconsin legislature was unconstitutional. But the Supreme Court unanimously reversed and remanded. Roberts wrote the opinion for the court and held that the plaintiffs failed to prove that they lived in districts that had been subjected to gerrymandering and, thus, did not show the personal injury required for standing.

The court concluded: “We therefore remand the case to the district court so that the plaintiffs may have an opportunity to prove concrete and particularized injuries using evidence—unlike the bulk of the evidence presented thus far—that would tend to demonstrate a burden on their individual votes.”

Justice Elena Kagan wrote a concurring opinion, joined by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen G. Breyer and Sonia Sotomayor. Kagan strongly condemned partisan gerrymandering and wrote: “Partisan gerrymandering, as this court has recognized, is ‘incompatible with democratic principles.’ More effectively every day, that practice enables politicians to entrench themselves in power against the people’s will.” She encouraged the plaintiffs on remand to prove that they have been harmed by partisan gerrymandering and also to present their claim based on “an infringement of their First Amendment right of association.”

Back in business

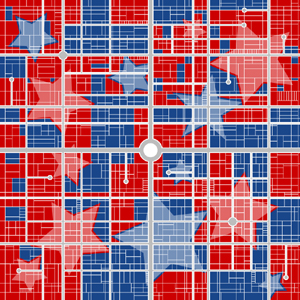

Rucho arose in North Carolina, essentially a purple state, leaning red. President Barack Obama carried it in 2008. But Utah Sen. Mitt Romney won it in 2012, and President Donald Trump did in 2016. Each election was decided by a narrow margin. Republicans got a slight majority of the votes cast for the North Carolina state legislature and drew election districts to give themselves a supermajority of both houses.

Republicans then drew congressional districts using what they called “partisan advantage” criteria. They stated that their goal was to draw districts for the congressional delegation from North Carolina so that there would be 10 Republicans and three Democrats. They succeeded. In 2016, the statewide vote for members of Congress was nearly tied, but Republicans won 10 of 13 races.

Lamone, which arose in Maryland, involves a Democratically controlled state legislature drawing a district for a congressional seat to elect a Democrat. Like in Rucho, a three-judge federal district court panel found this to be unconstitutional.

Many issues are presented in these cases.

• First, who has standing to challenge partisan gerrymandering?

• Second, can federal courts hear challenges to partisan gerrymandering, or are such suits inherently nonjusticiable political questions?

• Third, if federal courts can hear such challenges, does partisan gerrymandering violate the First Amendment because it is discrimination against voters because of their political party affiliation or deny equal protection as a form of vote dilution?

One the one side, challengers argue that partisan gerrymandering is “incompatible with democratic principles.” It allows a political party to entrench itself in power. It is supposed to be the voters who choose their elected officials; partisan gerrymandering means that elected officials are choosing their voters. As Kagan expressed last year, “only the courts can do anything to remedy the problem because gerrymanders benefit those who control the political branches.”

On the other hand, the states and their amici argue that the federal courts should stay out of this and leave the matter to the political process. They raise the concern that the court constantly would be enmeshed in districting disputes all over the country. The argue that the court got it right in Vieth: Challenges to partisan gerrymandering should be dismissed as political questions.

Roberts, Thomas and Alito have joined opinions rejecting federal court involvement in the issue of partisan gerrymandering. Just last term, Kagan, joined by Ginsburg, Breyer and Sotomayor, expressed the view that partisan gerrymandering is unconstitutional. The outcome therefore likely will depend on the two newest justices: Neil M. Gorsuch and Brett M. Kavanaugh. The decisions will have an enormous effect on our political system and on how districting is done after the 2020 census.

See also:

ABAJournal.com: “Chemerinsky: Racial gerrymandering can no longer be justified as proxy for party affiliation”

ABAJournal.com: “55 years after first SCOTUS appearance, lawyer is back for second redistricting case”

ABAJournal.com: “Supreme Court will consider racial gerrymandering case; could standing issue affect health law?”

ABA Journal: “Feb. 11, 1812: Gerrymander’s first sighting”

ABAJournal.com: “Partisan gerrymander in Maryland violates First Amendment right to political association, court says”

ABAJournal.com: “Supreme Court to hear two partisan gerrymandering cases after previous sidestep”