Chemerinsky: Gorsuch wrote his 'most important opinion' in SCOTUS ruling protecting LGBTQ workers

Erwin Chemerinsky. Photo by Jim Block.

There are many important implications to the U.S. Supreme Court's stunning decision June 15 that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act prohibits employment discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity.

In Bostock v. Clayton County, the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 that Title VII’s prohibition of employment discrimination “because of sex” protects gay, lesbian and transgender individuals.

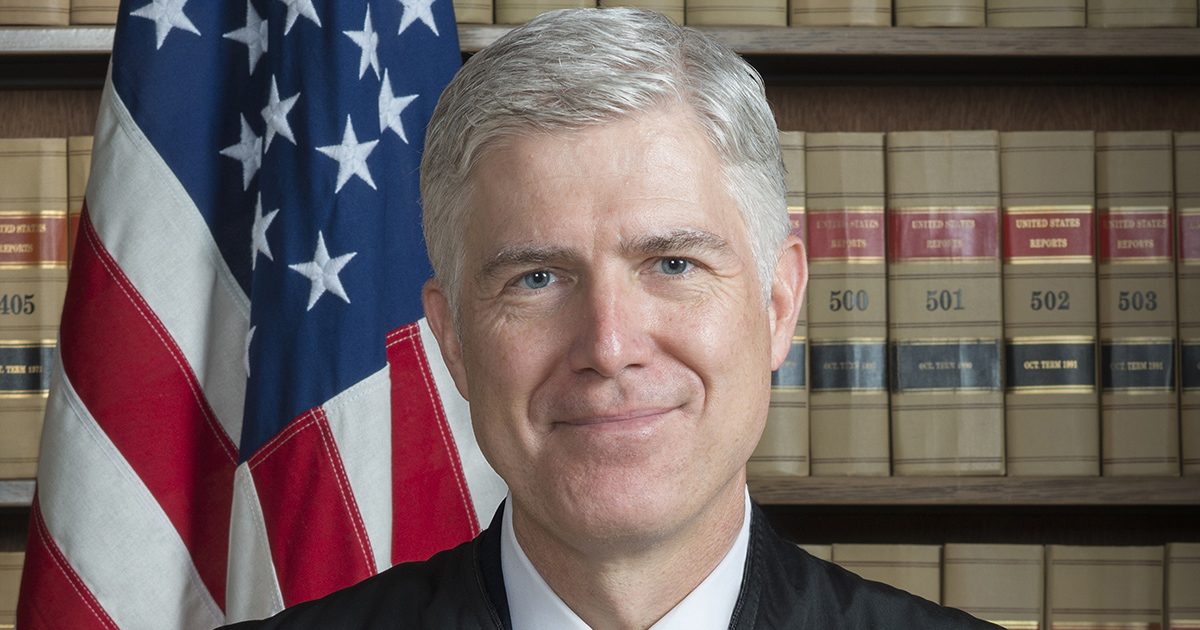

Justice Neil M. Gorsuch wrote for the court, joined by Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. and Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen G. Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan.

The decision

Actually, there were three cases before the court, though all were decided in one opinion. Bostock and Altitude Express v. Zarda involved men who were fired for being gay. R.G. & G.R. Harris Funeral Homes v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission involved Aimee Stephens, a funeral home director, who was fired for being a transgender woman.

The court’s holding was clear and emphatic. The court declared: “In Title VII, Congress adopted broad language making it illegal for an employer to rely on an employee’s sex when deciding to fire that employee. We do not hesitate to recognize today a necessary consequence of that legislative choice: An employer who fires an individual merely for being gay or transgender defies the law.”

Gorsuch’s majority opinion stressed the plain meaning of the prohibition of discrimination “because of sex” in Title VII. A simple example illustrates the basis for this conclusion.

Imagine an employee named Chris who never has met the employer. Chris and the employer communicate by text and email but never have met in person or talked by phone. Chris often has referred to a husband in discussing evening or weekend plans. When Chris and the employer meet, the employer is surprised that Chris is a man. The employer fires Chris, saying he does not want to employ gay people. If Chris was a woman, Chris would still have the job. That, by definition, is employment discrimination because of sex.

Likewise, Gorsuch said Stephens would have continued to have the position as a funeral director at R.G. & G.R. Harris Funeral Homes if she hadn’t transitioned. But she lost the job for being a trans woman. That, too, is employment discrimination because of sex.

Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. wrote a lengthy dissent, joined by Justice Clarence Thomas. Alito took a different view of the plain meaning of Title VII. He said discrimination based on sex, sexual orientation and gender identity have different meanings, and Title VII forbids only the former. Also, he argued, as did Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh in a separate dissent, that this should be for Congress to accomplish by amending Title VII, not for the judiciary to do.

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Neil M. Gorsuch.

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Neil M. Gorsuch.

The implications

First, and most obviously, employment discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity is now illegal in the United States. Only about half the states have laws that prohibit such discrimination.

In other words, prior to this decision, in about half the country, gay, lesbian and transgender individuals had no protection from employment discrimination. This is thus a huge change in the law providing protection from discrimination for millions of people.

Second, this decision likely means that other federal laws that prohibit discrimination because of sex also apply to forbid discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity. There are over 100 federal laws that prohibit sex discrimination in many contexts, according to Alito in the Supreme Court decision. The Obama administration adopted rules and guidance letters saying that they should be interpreted to also outlaw discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity. The Trump administration has rescinded most of these.

For example, Title IX of the Civil Rights Act prohibits educational institutions receiving federal funds from discriminating on the basis of sex. During the Obama administration, the assistant attorney general for civil rights and the assistant secretary of education for civil rights sent out a guidance letter to schools that Title IX applied to gender identity and required that schools allow students to use restrooms and locker rooms that correspond to their gender identity. The Trump administration has rescinded this.

Now, there is a strong argument based on Bostock that the statute must be interpreted to protect gay, lesbian and transgender students from discrimination.

Third, the court’s decision is likely to lead to litigation over the ability of employers to discriminate based on their religious beliefs. Title VII has a very narrow exception that permits employment discrimination on account of religion.

Employers who wish to discriminate based on sexual orientation and gender identity are likely to invoke the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. Also, they may raise free exercise of religion claims under the First Amendment.

Image from Shutterstock.com.

Image from Shutterstock.com.

Finally, Bostock has interesting implications for the level of scrutiny to be used for sexual orientation and gender identity discrimination under equal protection.

The Supreme Court has used intermediate scrutiny for sex discrimination since Craig v. Boren in 1976. Under intermediate scrutiny, a law is upheld if it is substantially related to an important government purpose. In 1996, in United States v. Virginia, the court also said sex discrimination would be allowed only if there is an “exceedingly persuasive justification.”

Only once has the high court articulated a level of scrutiny for sexual orientation discrimination. In Romer v. Evans, in 1996, the court expressly used rational basis review in striking down a Colorado initiative that repealed all laws protecting gay and lesbian people from discrimination and that prohibited the enactment of any new laws forbidding such discrimination.

In the cases involving marriage equality—United States v. Windsor in 2013 and Obergefell v. Hodges in 2015—the court found violations of equal protection but did not say what level of scrutiny was being used.

If discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity are seen as sex discrimination, then it would seem that intermediate scrutiny should be used under the Constitution when there is a challenge to government discrimination against gay, lesbian and transgender individuals.

It is possible that the court will say Bostock was just about interpreting the language of Title VII, and that it is different under equal protection. But there seems to be little basis for such a distinction once the court held that a prohibition against sex discrimination includes outlawing discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity.

By any measure, Bostock is an enormously important case. It certainly is the most important opinion written by Gorsuch since coming on to the court three years ago. It is a huge step to protecting gay, lesbian and transgender individuals from discrimination.

See also:

ABAJournal.com: “ABA amicus brief supports LGBTQ employees in Title VII discrimination cases”

ABAJournal.com: “EEOC doesn’t sign US brief telling Supreme Court that transgender discrimination is legal”

ABA Journal: “Supreme Court taking on big issues that have been percolating for a while”

ABAJournal.com: “Chemerinsky: It’s likely to be an amazing year in the Supreme Court”

ABAJournal.com: “Transgender woman in pending SCOTUS case dies at 59”

ABAJournal.com: “Job bias law doesn’t cover sexual orientation, Justice Department tells appeals court”

Erwin Chemerinsky is dean of the University of California at Berkeley School of Law. He is an expert in constitutional law, federal practice, civil rights and civil liberties, and appellate litigation. He’s the author of several books, including The Case Against the Supreme Court (Viking, 2014). His latest book, We the People: A Progressive Reading of the Constitution for the Twenty-First Century, was published in 2018.