Can true-crime documentaries do more harm than good?

Image from Shutterstock.

When done correctly, the true-crime genre produces digital page-turners, cliffhangers and whodunnits allowing viewers to play detective. While the best ones of the breed are engaging, informative and entertaining, it's the entertainment aspect that ultimately worries me.

Even though true crime does an admirable service to the legal community by giving the general public insight into the operation of law, does it also present potential negative consequences for the public’s perception and actual innocence claims as well?

THE CLIFFSNOTES VERSION

Image from Netflix.

Image from Netflix.While working for the NBC affiliate in Green Bay, Wisconsin, Jesse Wells reported on the original Steven Avery and Brendan Dassey trials examined in Netflix’s Making a Murderer documentaries. He covered dozens of court hearings and hundreds of hours of testimony in both cases—from the initial hearings to trial.

He was not a fan of the documentaries’ portrayal of the facts. He pointed out the bleach on Dassey’s jeans. He mentioned the numerous encounters Avery had with Teresa Halbach before her death and subsequent discovery of her remains on his property. He discussed testimony recounting Avery’s call to Halbach’s employers specifically requesting her to photograph automobiles at his home the day she disappeared. None of that was discussed in the documentary.

Due to his extensive knowledge of the cases, Wells equated debating them with individuals who had only seen the documentaries to discussing Shakespeare with someone who had merely read the CliffsNotes.

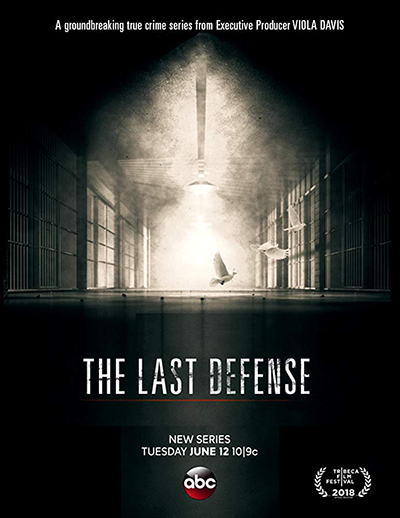

But as Aida Leisenring explained to me, there is only so much you can fit into a three hourlong episodes. Leisenring is a criminal defense attorney and one of the executive producers for the ABC anthology series The Last Defense, which, in part, chronicled the death penalty trial of Julius Jones. As part of the production team, she had a say in what information made the final cut. She says time constraints meant they could not include all of the exculpatory evidence.

I worry that if exculpatory facts must be cut due to time constraints, then the same probably holds true for damning evidence as well. The decision on what to use ultimately comes down to the team behind the documentary and the narrative they want to convey.

THE ‘AGENDA ISSUE’

As a result, I’ve heard multiple complaints about true-crime filmmakers’ “agendas.” An attorney associated with a recently televised case spoke with me on the condition of anonymity. A major network contacted him for the documentary, but he declined to participate because he felt the production team had an agenda from the outset. His remarks made me question to what extent filmmakers in this genre might allow their passion to pervade their editorial judgment.

If anyone wanted to speak about the potential for bias or agendas in true-crime documentaries, I thought it would be Ken Kratz. He is the much-maligned prosecutor from the Making a Murderer installments. According to Wells, the individuals creating the documentary consistently showed up to court with Avery’s family or his defense team. I had hoped Kratz could supplement Wells discussion about the allegedly obvious agenda behind the Making a Murderer team, but after some back and forth, he never answered the final questions I emailed him.

The agenda issue isn’t hard to fathom. It’s human nature. I’d venture there is a goal or purpose behind any creative endeavor, and true-crime documentaries shouldn’t be any different. If a narrative is involved, a film will be goal-driven toward establishing and furthering that narrative. That’s all fine and well as long as the facts are fairly presented for better or worse.

As Leisenring noted, “Every innocent person who is wrongfully convicted [will have] evidence against them.” While this is true, so is the flipside: Every guilty person who is correctly convicted will have evidence against them as well. That reality makes it difficult to know whether a true-crime documentary necessarily presents a frank depiction of both the positive and negative facts in a case.

After all, as David McKenzie—an attorney interviewed for The Last Defense—explained to me: “In order to tell a compelling story of innocence, you have to leave out the overwhelming proof of guilt.”

Image from ABC.

Image from ABC.“Proof” can come in many forms though. Maybe all it takes is a racially charged jury primed and ready to convict a black man in the Heartland. Perhaps for that jury, the “proof’ showed Julius Jones guilty from the get-go. McKenzie added that although The Last Defense discussed the racial aspect of the case, there is no substitute for actually fighting the stigma in court in real time. That uphill battle doesn’t totally translate through a television screen.

THE EFFECT ON ACTUAL INNOCENCE CLAIMS

Consequently, true crime can lead to false expectations for those seeking assistance with actual innocence claims. Moreover, it can potentially lead to negative blowback from the public in some circumstances as well.

One of the critical issues from The Last Defense was a bandana allegedly found in Jones’ home and placed into evidence in 1999 (the shooter in Julius’ case allegedly wore a bandana). However, no one tested the recovered bandana for DNA. Jones’ appellate attorneys pushed to have the bandana tested, and his storyline left off with the uncertainty as to whether it would be.

After The Last Defense aired, the bandana was finally tested. The results showed the presence of Jones’ DNA along with two other profiles.

Amani Martin, the director of The Last Defense, discussed the test results with me. Martin reiterated all of the issues surrounding the search for the bandana and the eyewitness account that made the bandana relevant in the first place. He reminded me that Jones’ was convicted largely through the testimony of informants involved in the underlying carjacking. He correctly noted that Jones’ DNA could have simply been contact DNA.

Regardless, we agreed that the DNA results from the bandana negatively affected Jones’ case in some form or another. According to Martin, “without a doubt, the finding of the DNA on the bandana damaged Julius’ case for appeal and the growing public sentiment that Julius had been wrongfully convicted.”

On April 1, the U.S. Supreme Court denied Jones’ petition for writ of certiorari. I worry that these disheartening developments in Jones’ defense might prejudice others claiming actual innocence. Jones’ case gained a great deal of national attention, only to fall flat in many regards subsequent to the documentary airing.

Nevertheless, everyone I discussed this column with spoke highly regarding the benefits true crime can provide the public. As Wells put it, “[true-crime documentaries] do a good job of exposing the warts of the system.” Martin agreed, explaining that “the films can educate the public about the shortcomings of the legal system by telling rich human stories in historical context.” I share the same sentiment.

PERMANENT FIXTURE OR PASSING FIXATION?

A gentleman called me in July about an article he was writing for a major publication regarding the true-crime genre. When I informed him that I believe the style will continue to permeate pop culture, he retorted that most of his interviewees thought otherwise. I found the exact opposite while writing this piece.

Despite its potential problems, I don’t think the genre is going to lose popularity anytime soon. The genre can be traced back to essays written in the late 1800s. Any literary or cinematic style that can last that long on its own will only grow and foster with the aid of the internet and streaming media.

What do you think? Do the pros of the true crime genre outweigh the negatives? Is true crime here to stay, or will we eventually move on down the never-ending list of instantly available entertainment?

Adam Banner

Adam R. Banner is the founder and lead attorney at the Law Offices of Adam R. Banner, a criminal defense law firm in Oklahoma City. His practice focuses solely on state and federal criminal defense. He represents the accused against allegations of sex crimes, violent crimes, drug crimes and white collar crimes.

The study of law isn’t for everyone, yet its practice and procedure seem to permeate pop culture at an increasing rate. This column is about the intersection of law and pop culture in an attempt to separate the real from the ridiculous.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.