ABA president calls for restructuring of immigration courts to increase independence

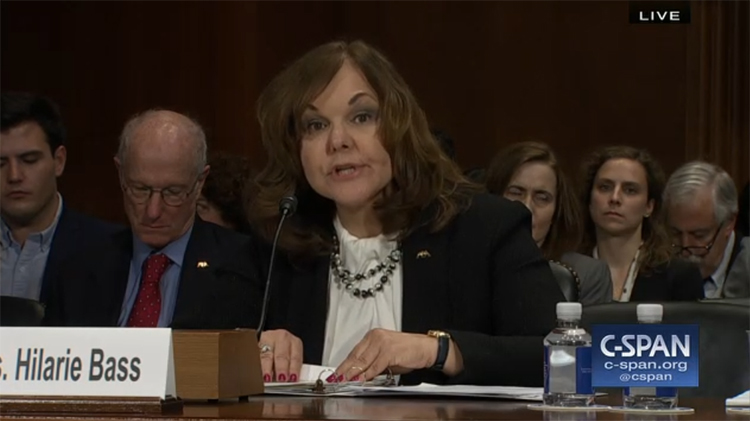

Screenshot of Hilarie Bass testifying before the Senate Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Border Security and Immigration.

ABA President Hilarie Bass called for an overhaul of the immigration court system in testimony Wednesday afternoon before a Senate subcommittee.

‘”We believe fundamental change is needed,” Bass said in her testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Border Security and Immigration.

Bass outlined the ABA proposal in a prepared statement submitted to the subcommittee. In the statement, Bass said immigration courts should be restructured as independent Article I courts, and immigrants should be given increased access to counsel and legal information. An ABA press release has a summary.

“The immigration courts issue life-altering decisions each day,” Bass says in the statement. “Yet, this system lacks the basic structural and procedural safeguards that we take for granted in other areas of our justice system.”

The ABA has long backed an independent Article I immigration court, but the association’s position has taken on “renewed urgency” in light of recent developments, Bass said in the statement.

The Justice Department announced April 2 that immigration judges’ job performance will be evaluated according to how quickly they close cases. According to Bass, production quotas can interfere with judicial independence, hamper the quality of decision-making, and lead to more appeals of decisions.

Immigration courts currently exist within the Justice Department, and their personnel and operations are subject to direct control of the attorney general. Immigration judges are career attorneys in the DOJ, and who can be removed and transferred without cause. That structure “is a fatal flaw to the reality—and perception—of independence,” Bass says in the statement.

Congress has created Article I courts, also known as “legislative” courts, even though Article I doesn’t specifically authorize the courts and they don’t legislate in the traditional sense of the word, according to this summary by the Federal Judicial Center.

Existing Article I courts include the U.S. Tax Court, the U.S. Bankruptcy Court, the U.S. Court of Federal Claims, and the Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims. Independence on an immigration Article I court could be bolstered by providing for set terms for judges, along with protections against removal without cause, Bass says.

Such immigration courts would likely attract more highly qualified candidates and increase perceptions of fairness, leading to greater acceptance of decisions, Bass said. That perception would likely lead to fewer appeals, and when appeals are taken, more articulable decisions that would make the reviewing tribunal more efficient. That should also lead to fewer appeals to the federal courts, she added.

Access to counsel and legal information are critical in ensuring fairness and efficiency in the immigration system, Bass says. Yet recent statistics show that only about 37 percent of those in removal proceedings—and 14 percent of those detained—are represented by counsel.

The ABA supports the right to appointed counsel for vulnerable populations in immigration proceedings, such as unaccompanied children, mentally ill and disabled individuals, and indigent immigrants. Because budgetary challenges make this unlikely in the near future, it is important that services to increase access to information be maintained and expanded, Bass said.

One particularly successful program is the Legal Orientation Program, which contracts with nonprofits to educate immigrant detainees about the law and the removal process, Bass said. The ABA provides these services in California and Texas “and we can unequivocally attest to the value of the program to the detainees and the courts,” Bass said in the statement.

Given the program’s benefits, the ABA was “dismayed and baffled” by a recent decision to suspend the program pending completion of a new cost-benefit analysis, Bass said.

Screenshot of James McHenry.

Bass testified after the director of the Executive Office for Immigration Review, James McHenry, defended using case completion numbers in evaluations of immigration judges and maintained that the immigration court system should remain within the Justice Department.

Immigration judges exercise independent judgment and discretion, zealously safeguard the court process, and advise the immigrants of their rights, he said.

McHenry spoke about issues contributing to case backlogs, and said his office is trying to address the problems. Currently there are 334 current immigration judges for about 700,000 pending cases, and there is authorization for 484 judges. McHenry said his hope is to shorten the hiring process, and to implement an e-filing system to increase efficiency.

McHenry said the Legal Orientation Program is being “paused” for further review, but he saw no reason why it wouldn’t be restored if it is found to be beneficial. The last study that found the program to be cost-effective was conducted in 2012 “under some unorthodox circumstances,” he said.

Bass countered that the 2012 study showed the Legal Orientation Program increased efficiency because it reduced the time for adjudications by 20 percent. Many people who are informed of their options conclude they don’t have a case and “self-deport,” she said. The ABA understands the desire to re-evaluate the program, she said, “but there is absolutely no reason” the program should be suspended during the analysis.

Immigration judges do inform immigrants of their rights, but that “hardly is sufficient compared to an hour-long program” of education delivered through the Legal Orientation Program, Bass said.

Updated at 4:20 p.m. to include hearing testimony.