Lawyer who suggested 'Breaking Bad' method to launder cash has conviction upheld by appeals court

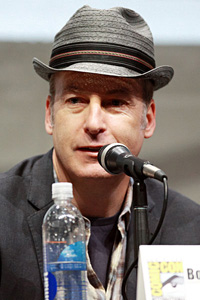

Actor Bob Odenkirk, who played lawyer Saul Goodman on “Breaking Bad”/WikimediaCommons

A federal appeals court has upheld the money-laundering conviction of a Cleveland criminal defense lawyer who suggested a technique employed by fictional lawyer Saul Goodman on the television show Breaking Bad.

Following Goodman’s lead, lawyer Matthew King suggested setting up a sham corporation to launder drug proceeds, according to the Cincinnati-based 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. “This did not end well,” Judge Jeffrey Sutton wrote (PDF).

King was convicted of two counts of money laundering and one count of attempted money laundering. He was sentenced to 44 months in prison.

King had fallen on hard times when he approached Marcus Terry, a man he believed to be a drug dealer, and offered to launder money for him, Sutton wrote. “As fortune would have it,” Sutton wrote, “Terry was posing as a drug dealer (he was a confidential informant in truth), and he told police about King’s offer.”

In meetings arranged by police, Terry wore a wire. King said he could set up a sham corporation, as he had seen on Breaking Bad, or he could launder money through his IOLTA account by providing fictitious legal services for Terry. They decided on the IOLTA approach.

Sutton began his opinion this way: “A sting operation blends fiction with non-fiction. The undercover officer feigns an offer to commit a crime and the individual accepts the offer, converting an offer to commit a crime based on untruths into a crime based on a true desire to violate the law. Sometimes, as it happens, the resulting crime blends nonfiction with fiction. In this instance, Matthew King, a lawyer, agreed to commit a real crime (by laundering the supposed proceeds of nonexistent drug sales) and offered to do so on the basis of a money-laundering technique observed on a fictional TV show (by imitating Saul Goodman, a lawyer character on Breaking Bad, who set up a sham corporation to launder drug proceeds).”

King had claimed introduction of the taped conversations violated the confrontation clause, and the trial judge improperly allowed the prosecution to ask about a prior arrest for cocaine possession.

The appeals court found no confrontation clause violation because the recordings were introduced to show that the laundered money was represented to be unlawful drug proceeds, rather than to prove that the statements were true.

The appeals court agreed the court should not have allowed the evidence of King’s prior cocaine arrest, but said the error was harmless.

Hat tip to How Appealing and Law360.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.