Meet 6 lawyers who are also racecar drivers

Cover Photo Illustration by Brenan Sharp, Stephen Webster and Tara Pattengale Photography.

"So I received an $895 race car," Porter says. "Thus began my hobby—obsession, really. It has been a problem of sorts ever since," he says wryly.

Porter is among a crew of attorneys who crave grabbing the wheel of a roadster, cranking its cylinders to 100-plus mph and burning rubber on the raceway. Whether it’s a need for speed, a search for an adrenaline rush, a love of automobiles or simply a passion from childhood, many lawyers relish racing cars in their spare time.

They say racing is a release from work-related tension. “Racing and restoring cars to me is a way to keep yourself sane from the stresses of practicing law,” Porter says. “It also is way cheaper in the end than psychotherapy.”

Yet Porter, among others, also compares car racing to legal practice. “I do see a mental similarity between practicing law and racing cars,” he says. “I race cars differently than other people do. I’ve been racing since the early 1990s, and I’ve never hit anybody and never crashed a car. That’s because I see the whole thing as a chess game. Every move has a consequence—similar to the process of being an effective trial lawyer. I try to plan three to four moves ahead when I race, just as I do when I’m practicing law.”

Retired counsel Jeff Carr also sees common treads between racing and law. “Racing has some profound similarities with the legal profession,” he says. “I came to realize that fighter pilots, race car drivers and lawyers are really a great deal alike. Those in all three professions tend to be intelligent, a bit aggressive, confident, competitive, and generally are ‘individual contributors.’ They can play in the sandbox but only when they lead, but they often prefer to play in zero-sum games alone.”

For his part, Porter always loved cars, something he inherited from his father, whom he calls “a car nut.” Porter used to go up to Lime Rock Park, a track in northeastern Connecticut, to watch the races.

However, his plunge into racing didn’t begin until the client paid his legal bill with the car, eight years after Porter finished law school at American University.

Now he races vintage cars in road races—most of the time in the United States but sometimes overseas.

Watch the video to see how our intrepid photographer, Don Jones, got this amazing shot of attorney Arthur Porter in the driver’s seat. Special thanks goes to the Bob Bondurant School of High Performance Driving and Pikes Peak International Raceway for loaning the car and the track.

After graduating from law school, Porter took a job with the law firm of Fulbright & Jaworski in Washington, D.C. In the early 1980s, he went to a law firm in Colorado Springs. In 1997, he started his own firm in the city. Porter specializes in family law, handles high-end commercial litigation and does some appellate work.

In addition to driving, Porter restores historic BMW race cars under the business name MotoPorter. “I am now involved in my 22nd car restoration,” he says. “It comes in spurts. I enjoy the process of working on the cars, getting them in great shape, learning their history, racing them and then selling them, and moving on to the next project.”

Porter traveled to Germany for a meeting with experts at BMW to help restore a rare BMW 3.5 CSL (coupe sport lightweight), a style built from 1968 to ‘75.

Even though he devotes much of his time to restoring cars, he still competes in at least five races a year. “I think I will probably keep racing until there is a physical issue,” he says. “The physical and mental exercise of restoring cars and racing cars is good for both mind and body.”

Porter credits his spouse’s support of his passion. “My wife is a miraculous woman,” he says. “She not only supports my hobby; she encourages it. She recognizes it is a bucket list-type thing for me.”

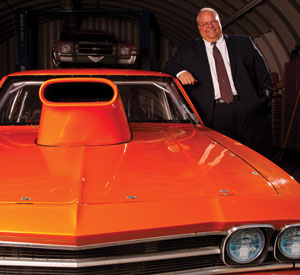

Arthur Porter stands with his own race car, which was torn down for inspection before the impending race season. Photo by Don Jones Photography

BACK TO THE TRACK

Carr, meanwhile, practiced law for 32 years, including as in-house counsel and general counsel. But his two big passions in life are racing cars and reforming the legal profession with regard to access to justice and the cost-effective delivery of legal services.

His passion for cars began a long time ago, as his family owned an auto body shop where he worked from the age of 11 through most of high school. He raced cars some in his late teens and early 20s but left that behind when he went to law school in the District of Columbia.

Carr embarked on his legal career, which culminated in his position as general counsel for FMC Technologies, a global supplier of systems and services to the oil and gas industry. The publicly traded company has approximately $7.5 billion in revenue. Carr was hired by FMC Corp. in 1993 as the international counsel for the company’s chemical business based in Philadelphia. In 1997, he moved to Houston to become the associate general counsel for the company’s energy equipment businesses, and in 2001 he became general counsel of FMC Technologies.

Since retiring, Carr has found introducing himself as a race car driver leads to more interesting discussions than saying he was general counsel of a successful company. Photo by Todd Spoth.

He retired as general counsel last August but remains committed to access-to-justice issues. In March, he spoke at the Georgetown University Law Center’s Corporate Counsel Institute on legal industry reform.

“The real crisis in access to justice is that the cost of legal services has simply become too expensive for most individuals as well as small and midsize companies,” Carr says. “There simply had to be a better way to deliver value to customers—and the industry needs to reform and restructure itself or it risks irrelevance.”

Since he placed legal work in the rearview mirror in August 2014, he has increased the amount of time on the track. Several years ago, he had rekindled his passion for racing cars. He attended a three-day open-wheel racing class at Skip Barber Motorsports at Mazda Raceway Laguna Seca in Salinas, California. He obtained his competition license and has been racing ever since.

He now races vintage cars with a group in Texas called CVAR, for Corinthian Vintage Auto Racing. “The cars are ‘classic’—another word for pretty old—and the drivers tend to be pretty mature about it,” he says. “Of course all drivers want to win, but it’s more about driving well and bringing these historic race cars and their drivers home safely.”

He says that introducing himself as a race car driver leads to more interesting discussions than introducing himself as the general counsel of a successful company. “It’s kind of funny, but for the first few months after I retired, I’d meet someone and would introduce myself with something like: ‘I’m retired, but I used to be the general counsel of a Fortune 500 company.’ Now, I simply say, ‘Hi, I’m Jeff Carr and I race cars.’

“Some, of course, think I’m a bit off,” he says.

Photo of Jeff Carr by Todd Spoth

AGELESS ENTHUSIASM

At 79 years old, John Hasty of Gastonia, North Carolina, still practices law and races his 1959 Triumph TR3A in vintage car competitions. He got his start a long time ago when he was a young teen desperate to get into the oval dirt track near his home.

In high school, he built street drag racers and later moved into sports cars in college. “If it has wheels and a motor I’ve always been into it,” he says.

Photo of John Hasty by Randy Piland

He attended Wake Forest University both for his undergraduate and legal studies, graduating from law school in 1960. He soon began competing in cross-country motorcycle endurance races and later competed in motorcycle road races on tracks such as Daytona, Road Atlanta, Mid-Ohio, Summit Point and Road America in Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin.

In his legal career, he represented the North Carolina Motorcycle Dealers Association and served as chairman of the board of the American Motorcyclist Association for about 10 years. He also developed an expertise in defamation law, representing television stations and other media outlets. He still practices as of counsel with the Gastonia law firm Mullen Holland & Cooper.

“I stopped racing in 1984 and started a professional race team with 250 cc Grand Prix motorcycles on the AMA national circuit,” he says, referring to the size of the engine. “My rider won the national championship in 1990.”

About five years ago, the lure of the track brought him back. One day a good friend invited Hasty to a vintage sports car race. He got hooked again. “I had a vintage Triumph TR3A race car within a few months and have been racing it now for about five years.”

Vintage racing differs from the auto racing seen on television. “Bumping into one another on the track is strictly forbidden,” he says. “If you hit someone on the track, you are probably going to be disqualified from the event; and if it is bad enough, your license will probably be suspended.”

“Many of the vintage cars are worth hundreds of thousands of dollars,” he says. “We race for earnest, but you never bump or crash a fellow competitor.” He also enjoys the camaraderie among vintage car racers.

Hasty has no intentions of stopping the practice of law or the racing of his Triumph. “I’ll do both as long as I’m able,” he says.

Photo of John Hasty by Randy Piland

THE AMERICAN DAYDREAM

Richmond, Virginia-based attorney Roman Lifson has been interested in cars as far back as he can remember—even during the first 10 years of his life, which he spent in Moscow. “I remember admiring the few American cars that were there in the 1970s.”

He remembers Moscow vividly, “including long lines for food, pillows, toilet paper and everything else you can imagine.” His parents immigrated to the United States “because Soviet Russia was an oppressive place to live and I would be facing military service,” most likely in Afghanistan. His father was a neurosurgeon and his mother an interpreter.

He got into racing in 2006 after a friend invited him to a track event at Virginia International Raceway, one of the premier road racing courses in the country. “I was hooked immediately,” he says. “For the next 18 months or so, I attended many more high-performance driver education events in my BMW M5.”

However, he began to believe that reaching speeds in excess of 160 mph in his family sedan was not the safest course of action. “I acquired a BMW M3 and built it out strictly for track use with the needed safety equipment—roll cage, harnesses, head restraint seat, HANS device and fire system.” His BMW M3 model was produced from 1995 through 1999 and is more performance-oriented than more standard models.

Photo of Roman Lifson by Tara Pattengale Photography

He later enrolled in race school through the BMW Car Club of America. For the last six years, he has been involved in wheel-to-wheel racing on road courses, including the Virginia International Raceway, Road Atlanta, Sebring International and Roebling Road.

He has had some harrowing moments on the courses. “I did have a brake failure at nearly 140 mph, which caused me to go off track and eventually impact a tire wall,” he recalls. “Although the car went into the tires up to the doors, I sustained no injury.”

Lifson is a partner in the litigation department of the Richmond-based law firm Christian & Barton. He has an active motorsports law practice, representing race track operators, track event organizers, race teams and individuals. “My motorsports practice is primarily in the road racing arena,” he says. “I represent several major road courses, which do host NASCAR-related events. That work involves contract matters for track rental, sponsorship, … risk management, critical incident handling and, when necessary, litigation.”

Lifson excels in litigation. “Litigation is a problem-solving business,” he explains. “It is also one that requires the lawyer to solve a riddle: What happened, how and why? The challenge of solving that riddle, and then presenting it to a jury when the opposition is trying to tell its own story, always appealed to me. Trial work is the culmination of extensive preparation.”

But he especially enjoys the community spirit of fellow racers at the BMW Club. “Many of us are close friends and competitors frequently help each other in the paddock when something needs repaired, which happens very often.”

His family supports his passion. “My wife understands how much I enjoy it and knows that I take all feasible precautions,” Lifson says. “My teenage children are likewise supportive and come to the track when their schedules allow. It was particularly fun to have my son—11 years old at the time—on the radio with me during a race.”

Photo of Richard Sebastian by David Mudd Photography

Nashville, Tennessee-based attorney Richard Sebastian serves as the managing partner at Ortale, Kelley, Herbert & Crawford, where he specializes in real estate and other commercial transactional work.

But since he was a toddler he has loved motor sports, automobiles and speed. “I was working on go-carts when I was 8 years old and drag racing in high school—the legal kind,” he recalls.

Drag racing presents its own set of dangers—just as in any type of motorsports. Once Sebastian had an engine that ran on alcohol explode. He could have been en-gulfed in flames that initially are difficult to detect. But Sebastian managed to extricate himself from danger and exit the vehicle.

“I suffered no injuries, but anyone knowledgeable of motor sports knows that bad things can happen quickly. You have to be prepared to face challenges.”

Sebastian participated in hundreds of drag races over many years, reaching speeds as high as 175 mph. Though he stopped drag racing when he entered law school, he has maintained an active presence with the mechanics of race cars.

Sebastian still owns a couple of dragsters, and he works on not only those but also oval-track race cars at his full-service auto repair shop and custom car business.

“I love the challenge of trying to make something perform better,” Sebastian says. “Whether it is taking a vehicle with 500 horsepower and upgrading it to 520 horsepower or rebuilding an engine for other specifications, I enjoy the process.”

Sebastian has applied the same no-holds-barred, all-effort approach to the practice of law, overcoming obstacles with a vigorous work ethic. He began working at Ortale Kelley as a runner and now serves as managing partner. “It takes perseverance and hard work to accomplish things in life,” he says. “Nothing ever gets better without hard work.”

Photo courtesy of Roman Lifson

SPEEDY RELIEF

For many lawyer-drivers, racing is a speedy sport, but it also helps lower their blood pressure. “For me it is a great outlet and it helps you forget all your problems and is good, relaxing relief,” Hasty says.

“It is all about relaxation,” says Sebastian. “It is my golf game. It is just what I like to do to relax.”

That’s not to say that racing cars is stress-free. Traveling at more than 100 mph can cause indigestion and requires the utmost concentration.

“Racing is definitely a terrific diversion from the practice of law,” Lifson says. “I would not describe it as a stress relief because racing itself is stressful, as is getting the car ready for each race weekend, traveling to the event, managing the work and family responsibilities during that absence.”

However, the benefits outweigh the burdens. “Racing is a tremendous outlet in that it provides a grossly engaging, demanding and challenging hobby that is very different from the daily work environment.”

“But when it’s all said and done, you get a great feeling of satisfaction in having engaged in something that you love to do,” Hasty says.

Racing also provides another type of boost. “I’d be lying if I didn’t admit that there’s an adrenaline rush,” says Carr. “I can’t be a fighter pilot, but I do race cars, scuba dive, and I love roller coasters.”

But it’s not just the danger that is intriguing. “Of course there’s something about the danger—but for me, it’s more about the discipline, the intense focus, the training, the consistency and the technical excellence. That way, when something does happen with the car or on the track, you’re ready to react and deal with the situation.”

Photo of Roman Lifson by Tara Pattengale Photography.

Describing the connection to lawyering, Sebastian notes that both attorneys and racers love competition.”As lawyers, everything is competition—and the same thing for racers,” he says. “In transactional work, you do everything you can to get the project completed. You know there will be pitfalls and you find different ways to solve the problem. A similar process takes place when dealing with the mechanics of race cars. We push these cars to the extreme, so we know there are going to be problems.”

“Both require precision, planning and execution,” says Lifson. “Both penalize heavily for mistakes. Both leave much that is outside of our control. In law, we have little or no control over the judge, opposing counsel and often witnesses. In racing, we have no control over the other competitors, weather, unexpected hazards on the track and mechanical problems. Both require the ability to react to the unexpected and to overcome nerves, and both offer tremendous satisfaction when those abilities are realized and goals achieved.”

Hasty also identifies several similarities. “It takes extreme concentration and skill to operate a race car,” he says. “It is not something one should undertake without having researched and learned all aspects of what is involved and then applying that knowledge in the best way possible. It’s basically the same approach I take with my law practice.”

This article originally appeared in the July 2015 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “Zeal Behind the Wheel: Lawyers at top speed.”

Sidebar

Photo of Lisa Vaughn Lumley by Danny Duran

In a Male-Dominated Sport, She Keeps Pace

Being female has not kept Fort Worth, Texas-based attorney Lisa Vaughn Lumley from following her passion for racing. She competes in BMW road races and also in events by the National Auto Sport Association."This is very much a male-dominated sport," Lumley says. "In fact, I'm almost always the only female at different races. When they call roll, I almost never have to answer, as I'm the only woman. But, especially in this region, I've earned the respect of the other drivers. I'm a good racer—I race hard and I race clean."

Since catching the racing bug after attending a track event in 2006, Lumley earned her competition license a couple years later, traded in her street car for two older cars—including a 1995 BMW M3 that became her racing car—began competing and became the BMW 2013 regional champ in her class.

Like the other racers interviewed, Lumley sees many parallels between racing cars and litigation. "The simple desire to win and to work hard to get there is an aspect of both racing and law," says the partner at Shannon, Gracey, Ratliff and Miller. "There is also the aspect of gathering huge amounts of information and making split-second decisions. You have to do that on the race track and also in the courtroom."

She finds both racing and law deal with solving problems. "With the car, you constantly are trying to find out and fix problems. It often involves logic problems, much in the same way I face as an attorney. As a lawyer, I often have to ask: 'How do I solve that problem? Does the law help; do the facts help?' "

Photo of Lisa Vaughn Lumley by Danny Duran

"Car nuts tend to hang out with other car nuts," she says. "One person told another who had a legal problem: 'I know a lawyer who is a car nut, and she may be able to help you.'"

Lumley wants to keep racing, hoping to join in more than the four to six regional races she currently competes in. "I sure would love to win a national championship in racing."

Given her track record for success, it's a fair bet that she will capture a national title.

"I do enjoy the adrenaline rush," she says. "I think what I find so fascinating is how on top of your game you have to be."

David L. Hudson Jr. is the director of academic affairs at the Nashville School of Law and has authored or co-authored seven books on sports.