From Cop to Counsel: Former police officer now serves the homeless as a social worker and attorney

Photo courtesy Jeff Yungman

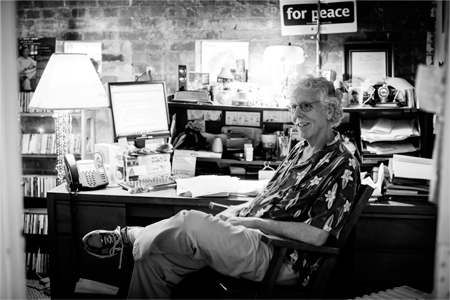

Jeff Yungman’s office is a good place to chill.

There’s a SpongeBob SquarePants lamp on the desk and a Peanuts Christmas clock on the wall. Every hour, a different carol plays. A Woodstock poster signed by Richie Havens and Grace Slick hangs on another wall, and more than 300 CDs jam the bookcases.

There’s always music. Jazz, rock and, of course, the Christmas carols—plus Hawaiian music every Friday.

“People come in frustrated or angry or scared about what their legal issue is, and my office relaxes them,” he says.

The office and the lawyer are both very welcoming, which may be why the Homeless Justice Project at One80 Place in Charleston, South Carolina, is so effective.

Social justice for all

The Homeless Justice Project provides civil legal services to homeless veterans, individuals and families, making One80 Place one of the few shelters in the country that has daily legal assistance on-site.

In his mid-60s, Yungman sees this as the greatest achievement of his life. But it was hardly a straight path to this success.

Yungman started his career as a street cop in New Orleans. He loved the city, and he loved his job. Somewhere along the line, though, he realized that he cared more about social justice than about criminal justice.

So he went back to school. A couple of years later, Yungman graduated from Tulane University with master’s degrees in social work and public health. He focused on child protection and homeless youths before moving to Charleston with his family. Years later, Yungman was clinical director at One80 Place when he heard that a new law school specializing in public law was opening in Charleston. One80 Place provided clients with strong support in social services but had no access to free legal services—something Yungman knew a sizable portion of his clients needed.

At age 52, he began studying at the Charleston School of Law. Then as a 2L, Yungman and the dean of students, Abby Edwards Saunders, opened the school’s first legal clinic—at One80 Place.

After bar admittance, Yungman worked as clinical director at the shelter and provided legal services until 2008, when a grant from the South Carolina Bar Foundation led to the founding of the Homeless Justice Project and Yungman’s full-time employment as a lawyer.

About 3,000 people have wandered into his office since then, seeking legal counsel and finding a lawyer with an unquenched zest for service.

An enthusiastic supporter of homeless courts, Yungman hosted Charleston’s first hearing in May at One80 Place. It went very well, he says.

“Everyone showed up on time—the judge, the public defender, the clerks, the city solicitor—everyone but the client,” Yungman recalls.

Yungman persuaded the court staff to wait while he jumped into his car to fetch the client. “We’re used to going out to find our clients. The people we deal with don’t have the same sense of time as we do.”

When the two returned, the case proceeded. The client, charged with trespassing at the Charleston Visitor Center, had completed his stipulated action plan. The city solicitor spoke so passionately in support of homeless courts that listeners were teary.

“The judge dismissed the charges, shook the client’s hand, and everyone applauded,” Yungman says.

Remembering a street angel

Of course, not all cases have such a satis-factory resolution. Life on the streets is hard, and people often don’t seek attention for the problems they are facing.

“I’ve seen more death than I ever expected here,” Yungman says. “I’ve been to more funerals than I can count. Sometimes, I’m named the next of kin because they have no one else.”

He remembers fondly one of his clients, now deceased.

Everyone called him “Hat” for the yellow plastic construction helmet he wore. But Hat wasn’t a builder. He was a street angel.

A husky military veteran, Hat was an instantly recognizable character on the streets of Charleston. He never missed the free food at the Hot Dog Ministry. Every Tuesday, he showed up at the cement slab under the I-26 bridge overpass. And he always stayed afterward to clean up.

Through a civil legal process, Yungman got Hat off the streets and into a small studio apartment. Then, Hat’s hoarding tendencies went into high gear.

He stuffed bags of blankets and clothes into his room. He piled more bags of water bottles and canned food on top. It got to a point where he couldn’t fit inside his home and had to go back to sleeping on the streets. Hat’s landlord learned of the situation and started the eviction process.

Yungman worked with Hat, gained his trust and finally got his permission to begin removing the bags from his apartment.

“I packed over 100 bags of stuff into my son’s van and stored it in my garage,” he says.

The eviction process was abated, and Hat retained his apartment. He was a kind man, Yungman says. He just couldn’t adjust to society after military service. When he died, the church was packed and the mayor spoke at his funeral.

Behind Yungman’s passion for his work is a simple philosophy for life. It’s best expressed by Kurt Vonnegut, whom Yungman names as one of his heroes: “There’s only one rule that I know of, babies—goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”

“That’s why I do this job,” Yungman says. “We’re not here for ourselves. We’re here to help others.”

This is the first in a new ABA Journal series, Members Who Inspire, where we will profile exceptional ABA members. If you know of members who do unique and important work, you can nominate them for this series by sending a note to [email protected].

This article appeared in the August 2017 issue of the ABA Journal with the headline “From Cop to Counsel: Former police officer now serves the homeless as a social worker and attorney."