Youth tackle football faces litigation over head injuries, along with proposals to ban the sport altogether

Pop Warner teams in Florida. Photo by John Panella/Shutterstock.com

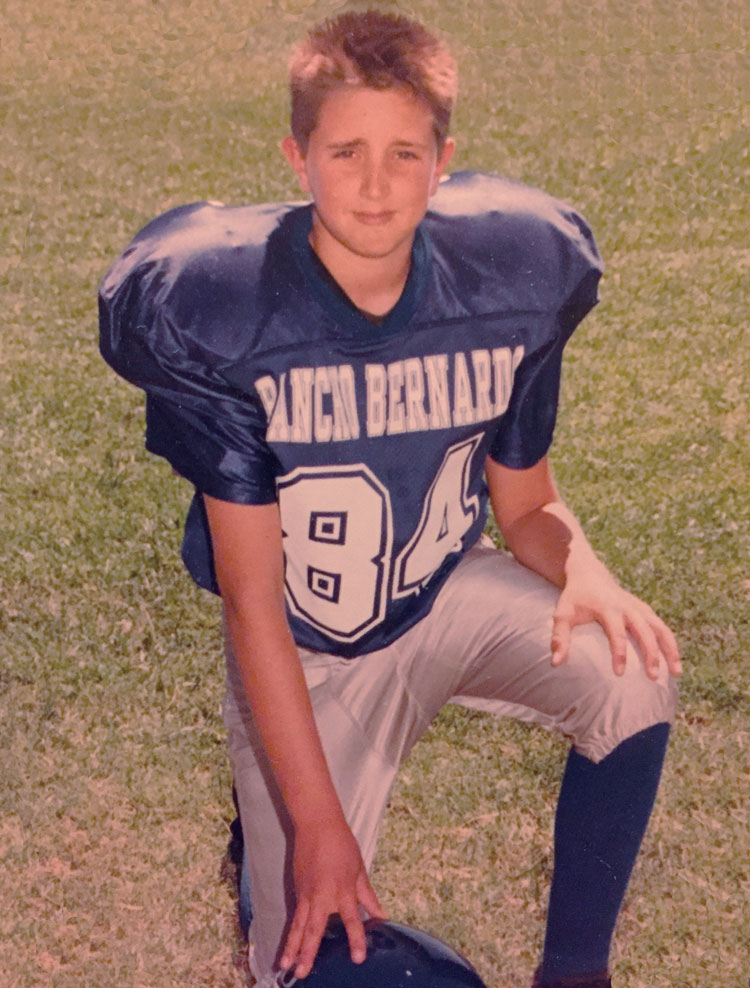

When he was 8 years old, Tyler Cornell proudly put on shoulder pads and a big helmet for the first time as he joined the Pop Warner Little Scholars football team in Rancho Bernardo, California.

For the next 10 seasons, his mother, Jo Cornell, spent hours on the sidelines watching her only child play peewee tackle football organized by Pop Warner, the largest U.S. youth football league. Her son loved the game and all that came with it— the friendship, the teamwork, the adrenaline rush.

Photo of Tyler Cornell courtesy of Jo Cornell.

He played for the Pop Warner team until he switched to the high school team, where he played on the line, taking down countless opponents, enduring countless hits to the head. Right before leaving for the University of California at Santa Barbara, Tyler Cornell changed.

He started struggling with depression and anxiety. He became impulsive and moody. He’d start a semester only to be hospitalized for mental health issues. Eventually, he transferred to the University of California at San Diego, which was closer to home.

But on April 3, 2014, after seven years of struggles, 25-year-old Tyler died by suicide.

Like most football fans in Southern California, Tyler’s mother knew the story of San Diego Chargers linebacker Tiaina Baul Seau Jr., better known as “Junior Seau”—how the linebacker had years of erratic behavior and how after the Hall of Famer’s suicide researchers at Boston University discovered he had chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a brain disease caused by repeated blows to the head.

Cornell knew Seau’s family was among the more than 4,500 litigants in a federal class action against the National Football League over concussion-related brain injuries.

In her grieving, she wondered: Could her son have had CTE, too, as a result of playing tackle as a child? Signs of CTE include depression, apathy, substance abuse, difficulty thinking, dementia, impulsive behavior and suicidality.

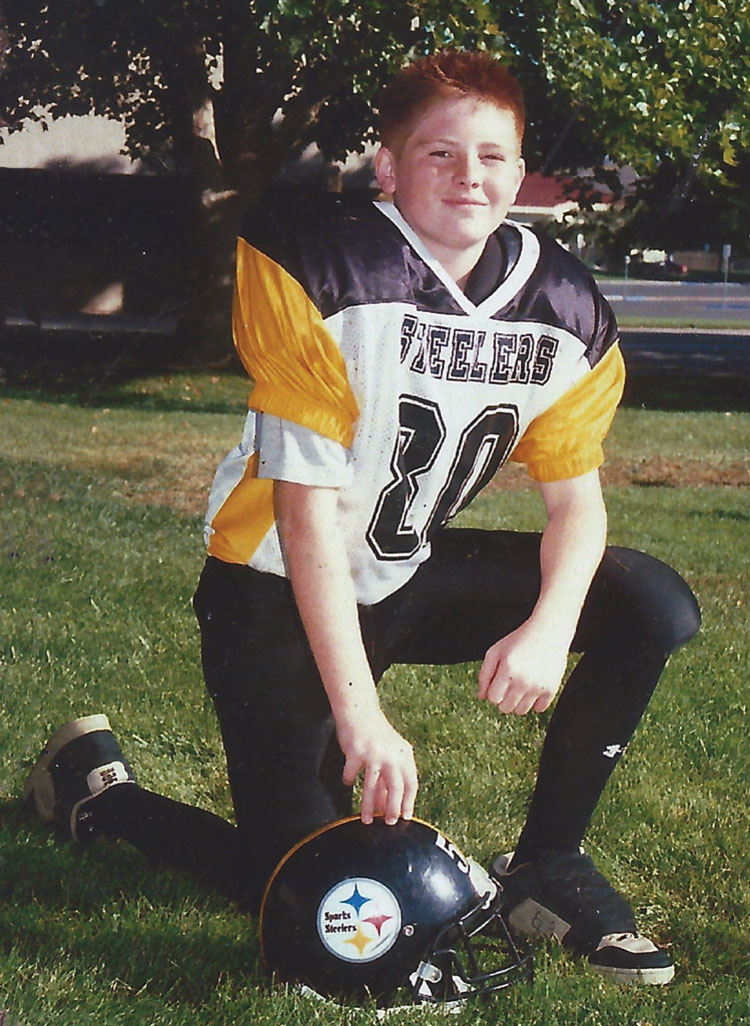

A few months later, she met Kimberly Archie, who lost her 24-year-old son Paul Bright Jr. after he recklessly drove a motorcycle and crashed just months after Tyler died. Like Tyler, Paul also played for years on a Pop Warner team through middle school.

Photo of Paul Bright courtesy of Kimberly Archie.

Both played in high school but not in college. Both struggled with erratic behavior and depression. Both mothers sent their sons’ brains to the Boston University researchers.

And both brains were found to have stage 1 CTE, making Tyler and Paul among the youngest players to be diagnosed with the disease.

Rethinking youth football

Parents such as Cornell and Archie have had enough and are seeking damage awards, as well as calling for bans on youth tackle football across the country. Several states already have considered such bans.

A class action suit against the Pop Warner youth football league filed by the mothers stands to be the first lawsuit to go to trial. The Langhorne, Pennsylvania-based organization, which is a unit of USA Football funded by the NFL, was named after football coach Glenn Scobey “Pop” Warner.

For the past decade, as the list of former NFL players coming forward with dementia and depression grows, professional tackle football has increasingly been under fire. Those flames grew after a well-publicized 2017 study by Boston University discovered evidence of CTE in 110 of the 111 brains that had been donated by families of deceased NFL players.

The backdraft is now moving toward youth tackle football, played by nearly 1 million kids. Another 2017 study by BU researchers fueled that fire, finding that children who played football before age 12 had more than twice the risk of problems with behavioral regulation, apathy and executive functioning—and more than triple the risk of clinically elevated depression scores.

“Football is a brutal sport,” says Robert Finnerty, a partner at Girardi Keese, the Los Angeles firm representing Tyler’s and Paul’s survivors in the civil suit. “The NFL cases brought forth the idea that trauma to the brain can result in serious consequences. This is just a continuation.”

Since January, five states—California, Illinois, Maryland, New Jersey and New York —have discussed laws banning tackle football for kids before reaching their teen years.

“I don’t hate football,” says Illinois state Rep. Carol Sente, D-Vernon Hills, who sponsored that state’s bill. “But can’t you just wait while the child’s brain is in a more developmentally stable state before you play tackle?”

This article was published in the August 2018 ABA Journal magazine with the title "Hard Hitting: Youth tackle football faces litigation over head injuries, along with proposals to ban the sport altogether."