Which law firm is the oldest in the United States?

The Denver Gavel—originally a carpenter’s mallet bought for 17 cents in 1878 by Francis Rawle, one of the founders of the American Bar Association—served in the hands of ABA presidents until 1946. Photo by Tyllie Barbosa.

Guinness World Records may be the pop culture authority on the world’s oldest person. But when it comes to figuring out which is the oldest law firm in the United States, Guinness is silent—but the Internet isn’t.

The title belongs to Rawle & Henderson, the venerable firm begun in Philadelphia—home of Independence Hall and Ben Franklin—just seven years after the nation was born.

Another firm, Howard, Kohn, Sprague & FitzGerald of Hartford, Conn., describes itself on its website as “the oldest law firm in continuous practice in the United States.” But by its own claim, it was founded in 1786 as the law firm of one Enoch Perkins. That makes it a mere 228 to Rawle & Henderson’s 231.

Thomas A. Kuzmick, a Rawle & Henderson partner, says he wrote to Howard Kohn a couple of years ago, congratulating the firm on its longevity and asking about its claim to be the oldest, but got no response. The Howard Kohn site does not refer to Rawle & Henderson, and the Hartford firm did not respond to ABA Journal requests for an interview about its website declaration.

That is a far different response, Kuzmick says, than Rawle & Henderson got from Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft, which at one time also claimed to be the oldest law firm in the United States. The white-shoe megafirm backed off after “a friendly reminder,” Kuzmick says. Cadwalader now calls itself “one of the nation’s oldest law firms (and the oldest continuing Wall Street law practice in the United States),” a claim no one disputes. Its birth date, 1792, makes it a mere infant compared to Rawle & Henderson.

John McMeekin, Timothy Abeel and Thomas Kuzmick are members of Rawle & Henderson’s executive committee. Photo by Gene Smirnov.

FRIEND TO FRANKLIN

The Philadelphia firm’s founder, William Rawle, knew Franklin, who as the U.S. ambassador to France helped Rawle return to America after law school abroad. Rawle also rubbed shoulders with George Washington, who appointed him the U.S. attorney for Pennsylvania.

Rawle was, among other things, a litigator—no doubt sending legal documents long before anyone drafted the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure or published Purdon’s Pennsylvania Statutes Annotated. The Westlaw database includes a case from 1786, Kunckel v. Baker, in which Rawle represented the defendant/appellant in the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. It was an interlocutory appeal on a procedural issue. (Sound familiar?) But he also had 18th-century substantive victories. In 1795, in Lloyd’s Lessee v. Taylor, the Pennsylvania high court ruled for Rawle’s plaintiff client in a dispute over executors’ power to sell land when a will directed the sale but failed to specify who should carry it out.

There were five generations of Rawles at the firm up until 1930—ending with Francis, one of the founders of the American Bar Association. As the lawyers gathered in Saratoga Springs, N.Y., for their initial meeting in August 1878, it was Francis who discovered they forgot to bring a gavel and hustled off to a hardware store to buy a carpenter’s mallet. That mallet, now decorated in silver and gold, perseveres as the symbol of the ABA.

In 1913 Francis Rawle brought into the firm Joseph Henderson, who later became an ABA president.

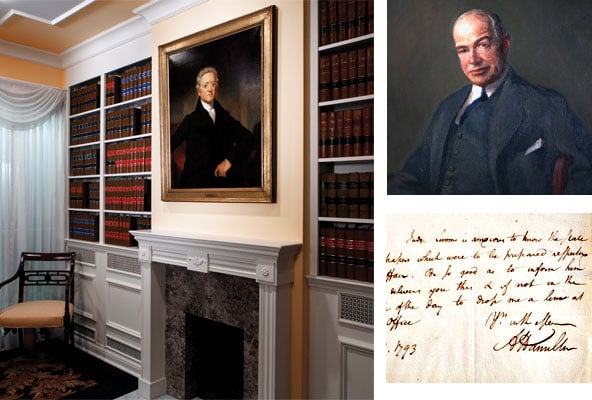

Inside the oldest law firm’s hallowed halls is founder Rawle’s portrait (left) by Henry Inman as well as founder Joseph Henderson’s portrait (above right) by Russell Recchion and a framed letter penned by none other than Alexander Hamilton in 1793 (bottom right). Photos by Gene Smirnov.

BRIGHT TO DARK TO BRIGHT

In the 20th century the firm was regarded in Philadelphia and the mid-Atlantic area “as a highly qualified firm of trial attorneys,” according to Kuzmick, a senior member of the firm’s executive committee.

“In the late 1980s and early ’90s,” he recalls, there was “a movement afoot in the legal profession that in order to succeed, everybody had to be full service.” His firm expanded into other areas, including tax and bankruptcy, but “it didn’t work out.” The firm then shrank from 72 lawyers to 27.

But despite the “dark years” in the mid-90s, the firm’s senior members believed fervently that they could not let two centuries of history die, Kuzmick says. “No way in hell we’re going to allow Rawle & Henderson to close on our watch,” he says. And in 1997, “we embarked on creating what you see today—120 attorneys spread over five states.”

The firm has three offices in Pennsylvania (the Philadelphia home office, Pittsburgh and Harrisburg), along with offices in Delaware, New Jersey, New York and West Virginia.

In the home office, modern in almost every sense, there is a letter from Alexander Hamilton to William Rawle on display. It was sent in 1793, while Hamilton was U.S. secretary of the Treasury, and reads: “Judge Simms is anxious to know the state of the papers which were to be prepared respecting his affairs. Be so good as to inform him if he delivers you this note; if not, in the course of the day drop me a line at my office.”

The late George M. Brodhead, a Rawle & Henderson chairman, once interpreted the missive for the Philadelphia Inquirer: “What we have here is a seemingly innocuous note that actually is one lawyer advising another to get a move on.”

IN THE NICHE

Rawle & Henderson has thrived on the opposite of being all things to all clients. “You need to be thought of first by your clients or potential clients as being in a niche,” Kuzmick says. “Our niche has been being trial lawyers on the defense side.”

On its 225th anniversary in 2008, Arlen Specter introduced a resolution in the U.S. Senate honoring Rawle & Henderson as the nation’s oldest law firm and hailing it as “a firm of national distinction whose reputation is based on the noble accomplishments of its founders and its commitment to providing quality legal services.”

The resolution was referred to the Senate Judiciary Committee and then, not unlike some legislation in present-day Washington, was apparently never voted on by the full Senate. There is no record of a roll call on the resolution, according to the U.S. Congress website.

That doesn’t seem to matter, especially to Rawle & Henderson today. The legacy is in the law books—and in the forefront of the partners’ minds.

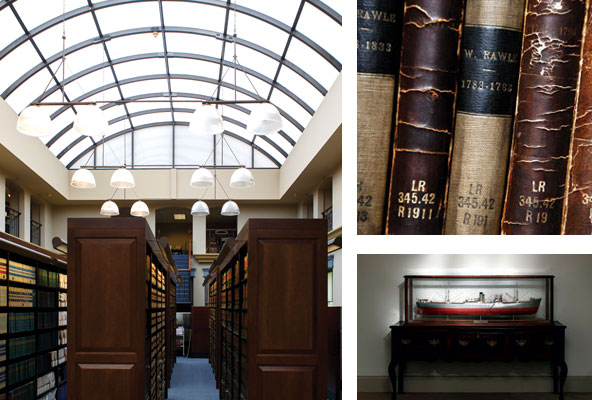

Rawle & Henderson’s Philadelphia office includes a model of the Nailsea Meadow (below right) and a bevy of law books—some of which were written by their very own founder, William Rawle (above right). Photos by Gene Smirnov.

This article originally appeared in the February 2014 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “The Old One: Philly firm’s history dates back to Ben Franklin.”

Charles DeLaFuente is a lawyer and freelance journalist in New City, N.Y.