Immigrants coming to the U.S. face legal uncertainties along with difficult living conditions and the pain of family separations. Yet a hope that opportunities will outweigh the travails is strong with many new arrivals.

That's something lawyers who help immigrants understand well—including those who are immigrants themselves. Some of them came to the United States with scant resources and developed an understanding of what it's like to be a child moving to a new home dramatically different than the one they left.

They also understand the frustrations. There is a sense that if you don't have experience doing immigration work, the system is almost impossible to understand—even if you are a lawyer. Backlogs in both detention centers and immigration courts are a significant concern, as is access to lawyers. And while the problems are often blamed on the government, one immigration court judge says counsel are sometimes responsible for creating inefficiencies in the process. Part of his job, he says, is to keep things moving.

We've talked to nine lawyers and judges about their experiences with the U.S. immigration system. Here are their stories. —Stephanie Francis Ward

By Danielle Braff

Kwabena Larbi-Siaw had one overriding goal as a child: He wanted to become an American citizen.

"America has done a great marketing job," says the Ghana native, describing the world of overabundance he expected to find once he reached the United States. He had a vision of unlimited food and supermarket choice excess. Now that he's here, he isn't any less amazed by the quantity of food available.

Larbi-Siaw, who goes by Koby, spent his childhood binging American TV shows and cheering on the Chicago Bulls from 5,900 miles away in the city of Accra. His mother worked at an international school in Ghana, which Larbi-Siaw attended, and it brought him face-to-face with other cultures and immigration issues.

"I think that subconsciously, I was working for a life in immigration law," Larbi-Siaw says. "Ghana is pretty much a mix of developed and underdeveloped. Even when you grow up with privilege, you are still seeing the harsh realities of life."

Those harsh realities seem to dissipate in America, which is why Larbi-Siaw was determined to move here—and help others do the same. He started reading the Encyclopædia Britannica to learn more about life outside his bubble, and he memorized the capitals of each country so he would have a conversation starter with people who lived outside Ghana.

"I would meet someone and mention the capital of their country," Larbi-Siaw says of his party trick.

His vision was fulfilled when his father moved the family to the Midwest in 1986 for two years to do an MBA program at the University of Minnesota. In 1998, Larbi-Siaw applied to college there too.

But Beloit College in Wisconsin is where his American food dream was unlocked, confirming to him that America is the best country ever.

"I remember going to the cafeteria to order a sandwich, and she listed off 22 different cheeses. And then she went on to bread," he says. "We had a cereal bar that had about 50 different cereals, and the only ones I knew were Frosted Flakes and Corn Flakes."

He knew he wanted to stay forever, so his next step was DePaul University College of Law. In 2008, he became an attorney, and in 2015, he became an American citizen via naturalization.

Now, Larbi-Siaw is living his American dream with offices in Texas and Chicago. He built his immigration law firm by visiting African churches to offer free information sessions.

"I have well-educated clients who have challenges navigating the paperwork." —Kwabena Larbi-Siaw

He spends the majority of his time helping clients understand how asylum works.

"The process is so complicated," Larbi-Siaw says, explaining that the form and instructions are in English, which is a major obstacle for many immigrants. Plus, the process is not immediately clear, and there aren't enough resources to get all of their questions and issues resolved. Additionally, there's a long waiting period. Larbi-Siaw has some clients who filed administratively and have been waiting in excess of four years for an interview.

"I have well-educated clients who have challenges navigating the paperwork," he says.

When he's not enmeshed in his law practice, Larbi-Siaw loves to spend family time with his wife and their 2-year-old daughter. He also returns frequently to Ghana, where he purchased a coffee farm with a friend from law school.

"In Ghana, you can have a driver and a maid at a low rate," he remarks. "But I can't handle the inefficiencies."

And the portion sizes.

By Anna Stolley Persky

Sonal J. Mehta Verma worries about the backlog in immigration courts—it can take the government a long time to issue work visas and extensions.

"Sometimes the process can take months, even if the need is immediate," says the Rockville, Maryland, lawyer, who helps companies bring in workers.

The immigration system is unpredictable, and it can be unclear why one visa application is approved and another is not, Verma says.

"These are people's lives we are talking about, and uniformity and predictability are needed in processing cases," she says.

When Verma's parents came to the United States from India in the 1970s, they were able to complete their own forms for lawful permanent residence and settle in Baltimore.

"Now the immigration process is more convoluted and less straightforward," she says. "Much of that has to do with fraud, misuse and a gaming of the process, but a lot of that also has to do with a governmental agency that cannot seem to train up and maintain a workforce of their own that cares about the cases they process."

Regardless of the challenges, Verma says, "I love what I do."

"Being a first-generation American gives me empathy for my clients and their situations." —Sonal J. Mehta Verma

She graduated from the University of Baltimore School of Law in 1998 and initially started working on asylum cases, often for victims of female genital mutilation. While she found that work inspiring, Verma ended up finding her calling by helping international businesses get H-1B visas for individuals from all over the world.

The program allows employers to hire foreign nationals in specialty occupations that require a bachelor's degree or higher. Verma has helped companies bring in software engineers, lawyers, architects and preschool directors, among others.

She also has clients petitioning to work in the U.S. as individuals recognized as outstanding in their field.

Some people think Verma's work is boring. She rebuts that and says it requires a lot of analysis to ensure each case is presented in the best manner to ensure approval. Most days are spent juggling multiple cases—and often putting out fires when visa requests encounter resistance.

Sometimes she helps obtain green cards for individuals who built lives in the U.S. and want to stay. But getting a green card can be difficult and take years, even decades. Verma says individuals from China, India, Mexico and the Philippines have especially long waits.

"Being a first-generation American gives me empathy for my clients and their situations," Verma says. "I want to help them get here to work here, and if they want to stay, make that process easier so that when it is finally done, and they have that green card in hand, they can finally breathe."

By Danielle Braff

Yolanda "Crystal" Felix always knew that while her immigration status was safe, her family could be deported at any time.

Felix was born in the United States and has some family in Mexico—some legally in the country and some here with no status.

"I grew up recognizing that some folks grew up in fear, knowing that they didn't have status," says the San Diego native, who serves as the managing attorney at the ABA Immigration Justice Project.

"We would go on camping trips and road trips, and knowing there would be checkpoints, we knew we couldn't invite everyone," she adds.

Growing up, Felix routinely spotted immigration arrests, witnessed families being torn apart and heard the screams as children were removed from their parents. No one in Felix's family had been to law school, so she thought that being a teacher would be a more attainable goal. But after spending a few years teaching English to middle school students in rural Japan, Felix gained enough confidence to give law school a shot.

Three years later, with a degree from Temple University Beasley School of Law, she was ready to help keep families together, focusing on expanding representation for immigrants detained at the Otay Mesa Detention Center, a federal facility near the San Diego-Mexico border.

Immigrants' biggest current need, Felix says, is access to counsel and resources. According to a 2022 American Civil Liberties Union report, at more than 40 Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention centers that were contacted, either no one answered the phone or the person who answered was unwilling or unable to answer the researchers' questions. Yet those who manage to obtain legal representation are 10 times more likely to have successful immigration cases, and almost seven times more likely to be released from custody than those without an attorney, the report states.

"We need more resources," Felix says. "They are fleeing their home countries, and they have legitimate fears, and they're being put in detention centers despite the majority not committing offenses. How are we going to ensure success, ensure they will get their bearings?"

By Julianne Hill

As a boy in Kansas, Sebastian Patti collected stamps. He had dozens. One was a little purple stamp with a picture of Queen Wilhelmina from the Netherlands, while others had images from places such as South Africa and Chile, piquing his interest in the world.

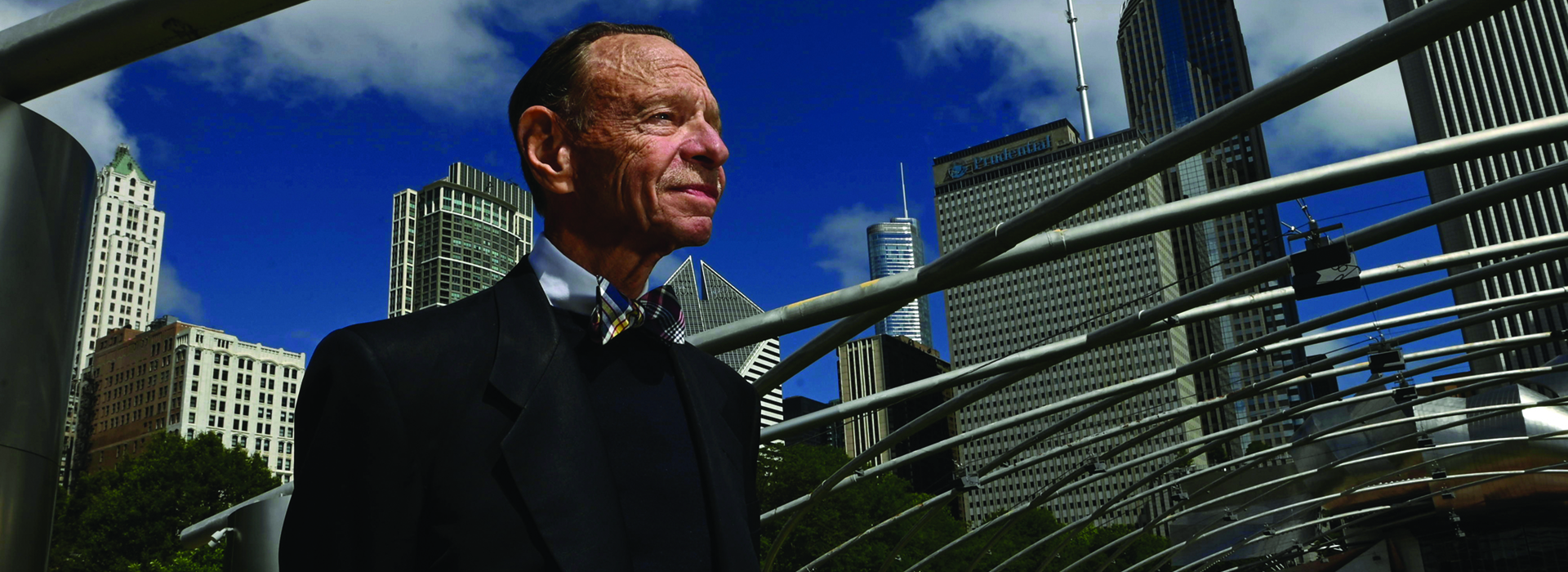

Decades later, he explores the globe by hearing cases in his courtroom at the Department of Justice Executive Office for Immigration Review in Chicago.

"When I review my cases for the week, Tuesday has an asylum case from Bangladesh, and Wednesday we go to San Salvador for a domestic violence case. Then we return to Haiti on Thursday and end up in the Ukraine on Friday," Patti says. "I have found it so educational."

The University of Kansas School of Law graduate's journey to the immigration court came after nearly 24 years as a judge—two on the Illinois Appellate Court—and many years as a member of the executive committee of the Circuit Court of Cook County in Illinois.

In late 2017, Patti felt he should consider retirement. But instead, he decided what he really wanted was a new challenge and to live in a warmer climate.

"The possibility of applying for an immigration judge position occurred to me, and I threw my toupee into the ring," he says. A year later, he accepted a job as a U.S. immigration judge in Los Angeles.

"Honestly, the first six months, I was not sure whether my lack of immigration law experience would dictate my future," Patti says. "It is not for the faint of heart."

The sheer number of immigration cases can be daunting. Typically, he hears three cases in one day—one in the morning and two in the afternoon. "I am mindful of the fact that there are another 45 who are waiting for me to put their case on my calendar," he adds.

"After 25 years on the bench, I became good at judicial economy." —Sebastian Patti

Patti thinks his time on the Illinois circuit court set him up for success. "After 25 years on the bench, I became good at judicial economy—how to narrow issues, move things along, ensure that a long-winded attorney or respondent gets to the point more efficiently," he adds.

But he was surprised to find that 90% of the applicants in nondetained immigration hearings have a lawyer. With attorneys on both sides, increased tension—and inefficiency—can result, Patti says. His best weapon to fight that situation? "A smile. It is simultaneously disarming and engaging."

At the start of Patti's career as an immigration judge, he and his husband moved to California. Patti enjoyed his newfound focus on immigration law, but the ideal of living in the Golden State wilted with the pandemic. In March 2022, the couple returned to Chicago, where Patti now hears cases.

Back in Illinois, his work continues in this fast-moving area of law.

"There are cases before the U.S. Supreme Court all the time," he says. "As immigration judges, we need to be completely familiar with and cognizant of the law as it evolves and develops."

Each day, Patti aims to live up to his oath of office.

"I have to instill in the litigants a sense that I listened carefully, I understood their position, and I rendered a decision based upon what I heard and what I read," he says. "If I can, then I've done my job."

By Anna Stolley Persky

Homero López Jr., who until recently practiced immigration law in New Orleans, said most people don't know the immigration system is quasi-judicial. Even lawyers are sometimes unaware that there's no right to counsel during the immigration process, he said.

"People don't understand that the of proof is flipped from the government to the immigrant to prove they are good immigrants," López said. "Instead of defending a client's rights, a lawyer can end up asking and then pleading and kind of begging."

López has since moved on to become an judge on the Board of Immigration Appeals. [Editor's note: After this issue went to print, the Executive Office for Immigration Review requested to include language emphasizing Lopez is expressing his own views and opinions, and does not represent the position of the EOIR, the U.S. Department of Justice, the Office of the Attorney General or the U.S. government.] When he was interviewed in March, before he started the new job, López declined to discuss his pending appointment. But he was open to sharing his experiences as an attorney.

In 2018, López co-founded a nonprofit focused on representing individuals held at immigration detention centers throughout Louisiana. Immigration Services and Legal Advocacy is based in New Orleans. The nonprofit has five attorneys and two supporting staff members. According to López, many of ISLA's clients are seeking asylum.

Louisiana's detained immigrant population has increased over the years as detainees are moved from other areas into the Bayou State, he said. The immigrants ISLA helps come from a variety of countries, including China and West Africa, although the majority tend to be from Central and South America. About half the clients are detained on or near the border, López said, and the other half come from internal transfers, such as individuals who have been accused of committing crimes or individuals who overstayed their visas.

"We have a constant flow of people needing our help and reaching out to us. Getting clients is not the hard part of this work in any way," López said in March.

Attorneys at ISLA tend to handle about 10 to 15 active cases at one time, López said. The work involves collecting evidence to help support each client's case, drafting motions, visiting clients in detention, attending hearings either virtually or in person and talking about the cases to family members. Until recently, López was a member of the ABA Commission on Immigration.

Before co-founding ISLA, López was the managing attorney at Catholic Charities Archdiocese of New Orleans, where he focused on representing unaccompanied children and immigrant victims of crime. Before that, he was a staff lawyer and later a supervising attorney at Catholic Charities Diocese of Baton Rouge. López was born in Texas and moved around a lot in his childhood because his mother was a migrant worker. He graduated from Southern Methodist University in Dallas and Tulane University School of Law.

By Anna Stolley Persky

Yifei He, a New York City-based attorney, works in "crimmigration" law, as he describes it. His clients are often immigrants who have been charged with or convicted of a crime.

He helps individuals at various stages of their immigration process, from people without documentation to those desperately trying to hold on to their green cards. The crimes his clients are accused of committing also vary—from shoplifting, drug possession and domestic violence to rape and other serious felonies.

"Everyone has a unique set of circumstances that led them to need my help," says He, the founder and owner of the Law Office of Yifei He. "I am deeply invested in each case. Immigration law can be complicated, so I have to go deeply into each client's issues and think through the potential consequences of making a particular move or argument."

He tends to handle about 10 to 15 active cases at one time. Crimes considered grounds for deportation include aggravated felonies, drug offenses, firearms offenses and crimes of moral turpitude, which can include prostitution or endangering the welfare of a child.

"Everybody is a human, and everybody can make a mistake." —Yifei He

At the age of 6, He emigrated from China to the U.S. with his parents.

"My background as an immigrant with immigrant parents influenced my passion for helping my clients," says He, who has an economics degree from McGill University in Montreal. He then went to the University of Connecticut School of Law, graduating in 2013.

In the mornings, He usually works on criminal cases, some of them court-appointed. Afternoons are often filled with visiting detention centers and prisons; representing clients at asylum, removal and other types of hearings; and meeting potential clients or updating current ones about the progress of their cases.

One of the most challenging aspects of his job is watching his clients wait, sometimes for years, in legal limbo—some of them stuck in immigration custody.

Part of the problem, He says, is the backlog in both the criminal justice and immigration systems. Another challenge occurs for clients who have committed a crime, but their home country won't take them back. Those clients, He says, can be held in immigration detention for years and years without any resolutions to their cases or any ability to restart their lives.

He believes in second chances.

"Everybody is a human, and everybody can make a mistake," He says. "My clients are people who came to this country to seek opportunities. If they have made a mistake in the past, that shouldn't mean we can't forgive them, and it doesn't mean they can't contribute something positive to our society."

By Danielle Braff

Luis Rios, a supervising attorney with the ABA South Texas Pro Bono Asylum Representation Project, never wanted to be an immigration attorney.

Baseball was his real dream, but it was also his pathway to a legal career.

Rios started playing baseball at the age of 5 and received a scholarship to play at Huntington University in Indiana. It was there that the Puerto Rico native received some life-changing advice from his history professor: Apply for law school.

The thought hadn't crossed Rios' mind. He envisioned himself hitting home runs for a major league team—or if not that, then maybe he could see himself focusing on a business career. But it occurred to Rios he could be a sports law attorney, and this revelation sealed the deal.

"I was in love with my future of being a sports law attorney," Rios says, speaking by phone from his apartment in Harlingen, Texas. He also has a home in Puerto Rico, and he is effusive about anything that interests him, from baseball to music—he used to play the trumpet—or his wife and family.

When Rios decided that the law was what he wanted to pursue, he was all in. He switched schools and enrolled in a pre-law program at the University of Puerto Rico for his senior year of college.

It wasn't baseball, but there was a connection.

"I learned from baseball that people were underrepresented, and players were steamrolled by teams and organizations," Rios says. "At that moment, I was into contract law, and I thought my knowledge and experience in baseball could be helpful."

He tried putting that knowledge to good use, but he couldn't find a job as a sports contract lawyer. Again, Rios shifted gears and decided to become a prosecutor, investigating public corruption in Puerto Rico. He later switched to become a defense attorney.

But again, he was sidelined by baseball. Rios' son was a baseball player as well, and he was recruited by a high school in Indiana. So he and his son moved to the Hoosier State, and Rios took a break from law practice for three years.

When he returned to work, he finally landed on a legal career that was close to his heart: immigration law.

"I fell in love with immigration," Rios says, explaining that it is very similar to criminal law. "The first thing that the judge does is read your allegation, your charges," he says. "People can tell me otherwise, but it's an allegation. I like that."

Of his clients, 90% are Venezuelans who entered legally with a visa and asked for asylum while they wait. Most of the people coming to the United States don't understand the process and don't know what's going to happen, Rios says. That's what makes legal immigration work so satisfying.

"I just want to help them understand what's going on," he says.

By Danielle Braff

César Magaña Linares' earliest memory dates to when he was 2 and screaming in terror on a plane.

He and his mother were en route to the United States from El Salvador to escape the natural disasters and extreme violence of his home country. They left his older brother and sister behind in the Central American country but hoped to be reunited with them in a few years. His father was already in Marshall, Missouri, trying to build a better life.

As soon as they got off the plane, the toddler learned his first English phrase from the detention officers: "How are you doing?

The answer: He was scared, but he would manage. The government let Magaña Linares and his mother join his father, and several months later, the United States designated El Salvador for temporary protected status. They were later joined by Magaña Linares' older siblings.

It wasn't smooth sailing. Two years later, the family moved to Nebraska, where they encountered racism and the ongoing fear that their temporary protected status could expire at any time. Magaña Linares' parents weren't English speakers, but he learned English quickly. By the time Magaña Linares was in kindergarten, he was the sole translator for the family. That included reading federal notices about their immigration status.

"I'm a lot more disillusioned now." —César Magaña Linares

By the 2010s, the family's problems were exacerbated by its members' mixed statuses: Magaña Linares' father had a pending asylum application; he and his mother had temporary protected status; his older brother and sister were Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals recipients; and his little brother, born in 2005, was a U.S. citizen.

In 2018, then-President Donald Trump's administration declared temporary protected status for Salvadorans would end. Magaña Linares heard the news on his way to work as a legal assistant for an Omaha immigration attorney. His thoughts flew back to El Salvador, where he would be living in a rainforest between two volcanoes.

"If I had to go back to El Salvador, what would I do?" he asks. Magaña Linares immediately got engaged in pro- "Dreamer" activism. Eventually, the government was sued, litigation stalled when a federal court enjoined the Trump administration's attempt on due process grounds, Joe Biden became president, and the temporary protected status termination was rescinded.

Magaña Linares now is an asylum lawyer with the Refugee Empowerment Center in Omaha and represents many unaccompanied children. He can relate to them, speaking their language and understanding their journey. But this cognizance makes his job harder. "One of us is living life, and the other isn't. I'm a lot more disillusioned now," Magaña Linares says.

His day-to-day life is determinedly American. Magaña Linares gets up early and writes out a to-do-list. He meets with his clients, goes to the gym, heads home to eat dinner with his wife and then binge-watches mindless TV. They're currently obsessed with Gordon Ramsay's Hell's Kitchen.

After work, he tries not to think so much about clients but often fails. A significant concern of his is people overestimating the maturity of immigrant teens.

"They see a 16- or 17-year-old boy who has been roughed up by the cruel realities of life, or a 15-year-old girl with an expressive attitude, and they seem to think they should not be treated as children," Magaña Linares says.

By Anna Stolley Persky

In July 2023, Stacey Rubin Silver, a Chicago lawyer, learned migrants were being taken in buses from Texas and dropped off in her city. She'd heard that many were from Venezuela and being left at police stations. She had to do something to help.

She baked some bread to bring as a welcome gift and drove to a police station.

"I looked around the police station, and I can never unsee what I saw," says Stacey, who owns Silver Law Office with her husband, Warren Silver. Families were camped out in the police station—exhausted, hungry, confused and lacking the basic necessities, including sufficient clothing. "I saw human misery," says Stacey, who practices real estate and zoning law.

The mother of four grew increasingly committed to making the lives of the people she met a little easier. She started a blanket and clothing drive, collecting bags and bags of items, including a fur coat and several pairs of Ferragamo shoes. Stacey also transported individuals and families when needed from a center with showers back to the police station. She and other volunteers put together hygiene kits.

The Silvers befriended a family originally from Venezuela. Both couples have a set of twins, which quickly connected them. Stacey studied Spanish in junior high, high school and college, and Warren took classes in high school. According to their family, the couple's Spanish skills have improved since they met the Venezuelan couple.

"I would encourage other lawyers to remember that they don't need to do legal services to do pro bono work." —Warren Silver

And by helping the family, who besides the infant twins have a little girl, the Silvers got a close-up view into the maze of a legal system migrants must navigate to try and stay in this country.

The night before their hearing, the Silvers looked up the court address on their friends' paperwork and figured out it was the wrong one. "Other people had to scurry around in downtown Chicago to get to the right place," Stacey says.

Besides helping the family connect with a lawyer to handle their asylum petition, the Silvers tried in other ways to ensure they are able to survive and, hopefully, thrive in the U.S.

When the Silvers met the family, both twins had been diagnosed with influenza. Stacey successfully pushed to get a room for the family at a shelter so the babies could get better and not create an epidemic by spreading the illness to others.

"I just stayed in touch with them and tried to make things easier," Stacey says. "I can't even tell you how much I love those children."

She helped them find an apartment near her home. In the fall, the Biden administration declared that people seeking asylum from Venezuela were eligible for temporary protected status and work permits. Stacey drove them to an immigration clinic where they could file the paperwork to start that process. She also drives them to doctor's appointments.

"I would encourage other lawyers to remember that they don't need to do legal services to do pro bono work," says Warren, who practices business and real estate law. "They can just help on a human level."