What Alfred Hitchcock can teach lawyers about villains and villainy

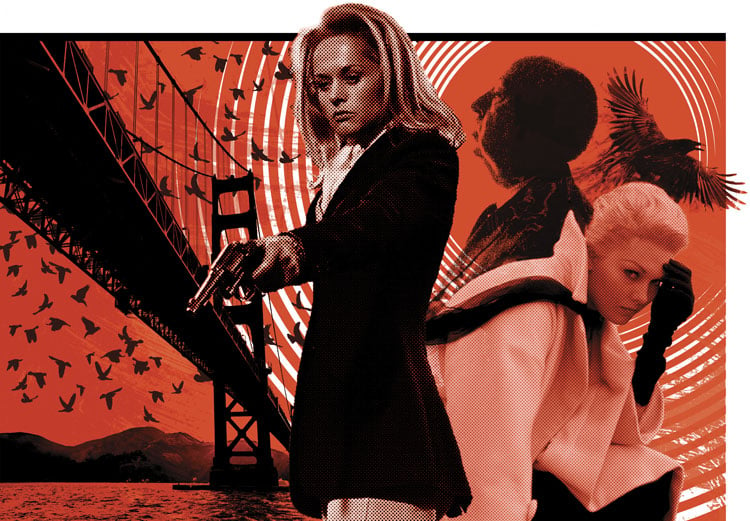

Photo illustration by Brenan Sharp

The more successful the villain, the more powerful the story. —Alfred Hitchcock

I was struck by the comments and wisdom of the experienced trial lawyers who shared their secrets to effective opening statements in the ABA Journal in “The First Word,” February, and “A Second Helping of First Words,” March. There was recognition of the power of effective storytelling—truthful and meticulous storytelling supported by evidence, of course, but storytelling nevertheless—in shaping outcomes at trial.

For example, Philip Beck wrote about structuring opening presentations to supply “a villain and a hero that every good story requires.” Beck provides this illustration: “In a pharmaceutical case, I start with the disease. The villain is the disease. The heroes are people like my client, who labored to defeat the villain. It is heartbreaking that the plaintiff is one of the few people who experienced the medicine’s warned-against side effect, but that is no reason to punish a company that has bettered all our lives.”

Some years ago, I worked as an associate in a firm representing plaintiffs in personal injury cases. Reading Beck’s observations, I intuitively watched a different movie. In my version of the story, the drug company would be cast in the villain’s role, “taking calculated risks with the lives of consumers—and factoring those risks into the costs of doing business and the price of its drugs and the profits from their sales.”

Both our openings are structured to begin with the depiction of a villain who sets the plot into motion. Both stories strive to depict compelling villains who must be stopped by “heroic” interventions. For it is only against the actions of the villain and the quality of the villainy itself that the character of the hero is tested and measured.

The plot thickens

Many trial stories are packaged into genre containers of melodrama. Here, I don’t mean merely the overblown exaggerations of afternoon television soap operas. Rather, melodrama is a classical narrative form that bifurcates the world into good and evil and simultaneously provides clear narrative correlates for both (e.g., the story’s heroes and villains). It is a form well-suited to combative courtroom storytelling, and trial lawyers draw intuitively and purposely upon this genre, empowering a jury or a judge to intervene, “heroically” fulfilling their oath to deliver justice.

In Anatomy of Criticism: Four Essays, Northrop Frye observes that the theme inherent in melodrama is “the triumph of moral virtue over villainy, and the consequent idealizing of the moral views assumed to be held by the audience.” In Telling Stories: Postmodernism and the Invalidation of Traditional Narrative, filmmaker and literary theorist Michael Roemer adds how melodrama “shows us as we are supposed to be and wish to see ourselves” and “permits us at once to believe in evil and to exorcise it by projecting it onto another—one who is unlike us: the outsider or stranger.”

Melodrama provides a secularized version of stories that go back to the Bible. These stories still matter, affirming our shared Western cultural values about right and wrong. Narrative theorist Peter Brooks says in his book The Melodramatic Imagination: Balzac, Henry James, Melodrama and the Mode of Excess, “We do not live in a world completely drained of transcendence and significance. Melodrama daily makes the abyss yield some of its content.”

But here is the curious rub for lawyers: As compelling as melodrama seems as a narrative form well-fitted to the courtroom, it seldom reveals the world outside the courtroom. Instead, it imposes a convenient shell and suggests a familiar and persuasive plot structure that works.

Simply put, villains as the embodiment of pure evil who purposefully propel the plot forward are pretty hard to come by these days. Perhaps that is why we still love our melodramatic movies so much.

For illustrations of archetypal villains, revisit Darth Vader’s deep-voiced hypermasculine superrationality beneath his black death mask in Star Wars. Or enjoy Heath Ledger’s masterful performance and his anarchic and compelling verbal mania within the tortured psyche of the Joker in Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight.

In contrast, Beck’s harmful disease is, honestly, not really a villain—it possesses no unified character or intentionality structured to test the will of heroic medical professionals. Likewise, the pharmaceutical corporation (aka “drug company”) in my plaintiff’s version of the same story does not embody evil—or even sinfulness—in a clever calculus of intentional choices apparently motivated by greed or deceit.

Nevertheless, trial lawyers often rely upon the conventions of melodrama—ascribing complex human motivations and intentionality to nonhuman actors (a disease, a corporation) by casting them as the villain. Popular movies provide helpful templates for lawyers attempting to better understand how, in turn, to shape evidence into compelling stories.

mastering villainy

Hitchcock was masterful at depicting villains, and capturing the imagination of his audience at different historical moments required various depictions of villainy. In his earlier melodramas, villains were “flat” characters—typically male, powerful and highly verbal, and from the upper classes—whose words concealed nefarious conspiracies and spawned plots testing the will of heroic protagonists.

Take for example, Hitchcock’s wartime melodramas The 39 Steps and Saboteur. Hitchcock redacted evil in plot-driven melodramatic and escapist entertainments. He provided diversion from the horrors of war and from truthful confrontation with the often unfathomable and consumptive totality of wartime atrocities that could readily overwhelm the audience. He manufactured calculated fright and surprise within clever, closed-ended plots, stocked with two-dimensional villains, depicting villainy that could be ascertained and defeated before the audience left the safety of the theater.

But it is Hitchcock’s later movies that provide narrative templates especially instructive for lawyers these days. For example, lawyers retelling Beck’s proposed defense-framing story, about the disease as a villain who must be stopped by the heroic interventions of doctors and pharma companies, might benefit from revisiting Hitchcock’s The Birds. Like that movie, Beck’s trial story must evoke our fear that nature can turn against us and embody our own darkest natures in malignant forces that grow evermore powerful. Risks must be taken. Heroic interventions are necessary to stop dark forces that have tipped the natural landscape out of balance. Of course, there are the costs of these interventions, sometimes there are “side effects,” and sometimes the innocent suffer. But the costs of inaction are intolerable.

Beyond Melodrama

My counterstory for the “villainy” of the pharma company might be modeled upon various narrative templates. Obviously, there is the villainy in Hitchcock’s early melodramas. The deceitful, powerful, highly verbal male villain, whose rhetoric purposefully conceals nefarious plotting, suggests the characterization of a defendant-corporation that thinks in and speaks the language of money and values profits over people. But an alternative counterstory may be suggested by two of Hitchcock’s psychological thrillers: Vertigo and Marnie.

Here, the villainy is within the compelling and complex characters at the center of both stories: Judy in Vertigo initially assumes the identity of Carlotta, as an accomplice to the criminal mastermind covering up his wife’s murder. She falls in love with the protagonist-hero, and her own identity intertwines with the character she has constructed. Marnie, a thief and compulsive liar, is cold-blooded and unable to feel. She refuses to confront the consequences of her actions. Both spin their stories and characters into elaborate self-deceptions. These stories may suggest a template for a plaintiff’s argument for punitive damages in Beck’s case—a counternarrative about a drug company pretending to be what it is not, unwilling to come clean and reveal the true motivations for its actions.

Whether we are aware of it or not, or admit it or not, litigation attorneys are storytellers who shape evidence into courtroom stories fitting genre conventions embedded in jurors’ imaginations. And we have much to learn from masterful popular storytellers, such as Hitchcock, who also do this work so artfully and so well.

Philip N. Meyer, a professor at Vermont Law School, is the author of Storytelling for Lawyers. This article appeared in the October 2017 issue of the