U.S. Lawyers Go for the Gold!

Illustration by iStockPhoto.com

See related story “Best Be Behavin’ in Beijing.”

Kelly Crabb made his first Olympics at the 2002 Salt Lake City winter games. Now he’s a member of the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics team. And though he has no shot at making Vancouver in 2010, he’s pushing to be a part of the Youth Olympic Games in Singapore in 2010 and the London summer team in 2012.

But Crabb isn’t an athlete.

“I wish I was,” laughs the Los Angeles-based partner at Morrison & Foerster. Crabb and his Beijing-based partner, Steven Toronto, act as international counsel to the Beijing Organizing Committee for the Olympic Games. In that capacity, Crabb and Toronto oversee legal work at Morrison & Foerster offices around the globe on issues such as venue construction, ticketing, broadcasting and intellectual property protection.

“We were engaged in the fall of 2002 and have worked with BOCOG ever since,” Crabb says. “It takes six years to get ready for the games. It’s quite an endeavor.”

Joining Crabb on the Beijing Olympics legal team are attorneys throughout the world. Some have worked in the Olympic movement for years; others are new to the games. Some were semiprofessional athletes—even Olympians—themselves. Whatever their background, they say Olympics work is challenging because of the breadth and complexity of the issues.

And, wording their responses carefully, they contend that Chinese culture—not its politics—has created issues they hadn’t anticipated.

Kelly Crabb.

Photo by Max Dolberg

SCHOOL CHUMS

Crabb’s Olympic journey began when he landed work for the Salt Lake City Organizing Committee, which handled the 2002 winter games. “My classmate at Columbia Law School was general counsel of SLOC,” explains Crabb. “He had a question about an agreement and called me, and I did that and several other projects for SLOC.”

That pinch-hit engagement served as an introduction to the Beijing gig. While at the Salt Lake City games, Crabb made a presentation to the Beijing Olympics legal team, which he believes was instrumental in getting the BOCOG contract.

“One of the big moments for us was when we were given the opportunity to host a member of BOCOG’s legal department,” Crabb says. “He didn’t see us doing a lot of work at the games, but we did our very best to impress him. We arranged meetings with our client, the SLOC, which rolled out the red carpet and hosted seminars. One seminar by SLOC was ‘things we wish we’d have known when we were in your shoes.’ That made a lasting impression because it came from people who’d just gone through the experience.”

(Crabb says he would have to get permission from his client before naming the Beijing representative to whom they pitched.)

Still, Crabb’s firm had to “apply” for the BOCOG duties, detailing its expertise in matters relevant to the games. “We had to go through a very involved process,” he explains. “But we thought we had a good shot. The one advantage we had was that we had done work on the Salt Lake City games, plus we had an office in Beijing. But if I recall correctly, there were more than 100 law firms that wanted to do this work on the international side. Our competitors were from the United States, the United Kingdom, China and Hong Kong.”

About nine months after submitting its application, Morrison & Foerster clinched the BOCOG deal.

Heading BOCOG’s domestic team in China is Wang Rui, a partner in the Beijing offices of King & Wood. Her firm, which also has an office in San Jose, Calif., competed with about 70 China-based and foreign firms for the work, Wang states. (She requested that questions be sent in advance via e-mail and sought permission from her client to be interviewed for this article.) Since being awarded the business, more than 100 of the firm’s attorneys have worked on Olympics matters; 30 are still doing regular Olympics work.

“Far in advance to the pitch, we conducted extensive research on hosting the Olympic Games and the corresponding legal issues,” says Wang, who is also a sports agent in China. “Based on this, the pitch documents prepared by the firm provided a detailed blueprint of the legal services that BOCOG may require.”

Other pluses, according to Wang, were the language skills of attorneys at her firm and the firm’s experience representing large-scale state-owned corporations such as Bank of China and People’s Insurance Co. of China, as well as foreign firms like AT&T and Wal-Mart.

Thousands of miles away in Lausanne, Switzerland, is Howard Stupp, director of legal affairs for the International Olympic Committee.

This isn’t Stupp’s first Olympic Games. That was in 1976, when the Canadian and two-time Pan American Games champion competed in both freestyle and Greco-Roman wrestling for Canada at the Montreal games—after suffering a bout of appendicitis only two months before. “I didn’t do well,” he admits. “My first match was against the eventual gold medalist, and he thumped me.”

Stupp again made Canada’s team four years later, but the country boycotted the 1980 Moscow games to protest the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979.

“I remember thinking that if me not going could save one life, I shouldn’t go,” explains Stupp. “I was very altruistic.”

But Stupp’s athletic efforts did lead to a different sort of win. It was through his wrestling contacts that he learned of an opening in the IOC’s legal department. “I thought I’d be here two to four years and then I’d go back to Canada,” he says. “Now I’ve been here 24 years.”

SPORTS FRANCHISE

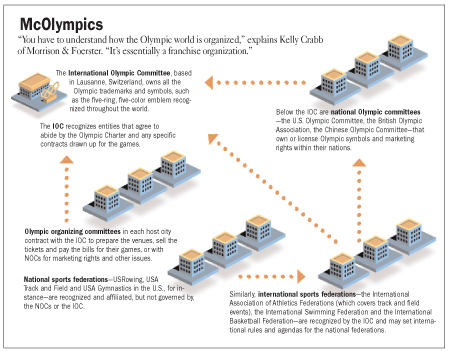

In addition to the Beijing organizing committee for the Olympic Games and the International Olympic Committee, other Olympic entities have been fielding their own legal issues. “You have to understand how the Olympic world is organized,” says Crabb. “It’s essentially a franchise organization.”

Heading the franchise is the IOC, which owns all the Olympic trademarks and symbols, including the five-ring, five-color emblem recognized throughout the world. “All rights extend from the IOC,” Crabb says.

Growing off the IOC like arms on an octopus are the city organizing committees and the national Olympic committees from 205 nations, territories, commonwealths, protectorates and geographical areas. The IOC also recognizes international and national federations for each sport in the games. (See chart, titled “McOlympics.”)

All those Olympic-related organizations have distinct functions, making the potential for legal work for each Olympic Games mind-boggling, and the complexity of each issue even more so.

For example, the creation of each Olympic Games logo is straightforward enough. However, once created, the logo must be registered and protected in more than 200 legal jurisdictions, and some of that work Crabb has helped oversee.

“There are certain centralized filing procedures, such as the Madrid Protocol, which will allow for the registration in more than one country,” he says. “These registrations, starting with Beijing, are done by the IOC. As a firm we answered questions and provided our analysis, but the filings were actually prosecuted by a Swiss law firm hired by the IOC.”

“The IOC has been taking more and more of the registrations in-house,” says Crabb. “In the future, the IOC might just do it all.”

And here’s another deceptively complex issue:

“You’d think the tickets would be fairly simple, but they’re not,” says Crabb. “There’s a master contract with the worldwide ticket sales organization, and there are lots of issues—like when you create a database of private information of the people who buy tickets, you have to comply with government mandates on privacy, and that’s a lot of work. There are 200 nations, and they all have different laws.”

Because attorneys in Morrison & Foerster’s New York City office have grappled with those issues for other clients, including banks and credit card companies, Crabb leaned on their expertise. “Work related to equestrian events has been done out of our Hong Kong office,” he says. “Construction work was done out of our Tokyo office. It would be very difficult for a small firm to do this work.”

All told, about 35 lawyers from Morrison & Foerster have done BOCOG-related work in the last six years. “As many as nine of our 18 offices were involved,” says Crabb, though he declined to disclose the amount of fees his firm has collected from its Beijing Olympics engagement.

Rana Dershowitz.

Photo by Allison Earnest

NEW PLAYER

Back stateside, Rana Dershowitz is an Olympic team rookie. In 2007, she joined the U.S. Olympic Committee and is now general counsel and chief of legal and governmental affairs at the Colorado Springs, Colo., organization. A former college skier and now a triathlete, she will attend her first Olympic Games in Beijing.

Before that, however, she’s got her hands full with legal issues related to the U.S. Olympic team. Her workload “varies depending on the day,” she says, in part because the USOC is charged not only with overseeing the country’s involvement in each Olympic Games, but also with its involvement in the U.S. Paralympics and the Pan American Games.

A common issue for Dershowitz is team selection. “We’re charged with overseeing selection procedures by which athletes are chosen,” she explains. “We’re not the subject matter experts on how to best select a team or individual in any particular sport, but we make sure sports federations’ guidelines are clear. If disputes arise, we have a role in resolving them before they go to arbitration.”

In one case, an athlete whose name the USOC has kept private, disputed the process for choosing crews on the U.S. rowing team, arguing that a subjective process based on a combination of factors was improper, and that the selection process should have been based strictly on speed.

“USRowing believes that you need coordination among the athletes and that it could figure out who the best four athletes were through its selection camp,” explains Dershowitz. “The athlete challenged that process, arguing the only way to pick team members was in a race-off.” In March, a ruling by the American Arbitration Association upheld the USRowing selection process.

“The USOC isn’t usually involved in arbitration over athlete selection procedures,” she says. “In this case, we were a party because the athlete claimed the selection camps were inappropriate, and we felt very strongly there needed to be recognition that there may be times that subjective criteria are important to selecting a team.”

Other than team selection, the USOC’s role in the Olympic Games is preparatory, says Dershowitz. “It’s to have a foundation in place should something happen and to ensure our athletes are educated on the rules at the games, how things will play out and what will be expected of them on and off the field, so they’re prepared for the spotlight they’ll find themselves in,” she says. “A lot [of the work] isn’t legal, but it’s where legal and business planning come together.”

Once she gets to Beijing, Dershowitz expects to be troubleshooting on-site. “If there are concerns about the contracts we’ve entered into, we’ll need to address those on the ground,” she says. “It’s really about being prepared for any and all contingencies, but not expecting them.”

CULTURE CLASH

But months before the opening ceremonies on Aug. 8, attorneys working on the Beijing games say they’ve run into challenges they’ve never before encountered. Some are the result of Chinese law; others are due to matters of Chinese culture.

The most complex, and most lucrative, legal issue in any Olympics may be broadcasting. “The broadcasting agreements are the single largest source of revenue for the games, and it took about two years to negotiate a draft,” says Crabb.“There are about 22 official broadcasters worldwide, and the largest is the United States—which is NBC this time. So that contract is probably the most important.

“There’s competition among the broadcasters for various things, such as whether they can have their own footage and what they can and can’t broadcast,” explains Crabb. “There’s also a facilities component. Every games has to have a broadcasting center that houses press and broadcasters. In Beijing, BOCOG anticipates serving 17,000 in that facility. For 17 days, it’ll be the largest broadcasting center in the world.”

One particularly thorny point required a workaround of Chinese law barring foreigners from owning broadcasting entities. Many nations, including the United States, have similar laws.

“Manolo Romero has been responsible for the broadcast of the last 15 games,” says Crabb. President of International Sports Broadcasting, Romero is a television executive who oversees the Olympic broadcast feeds to the world. “Everybody wants him to be in charge because he really knows what he’s doing, including the IOC and the rights holders who pay for the broadcast rights. But he’s a Spaniard.” After some legal maneuvering, Romero will now head the broadcast through a Chinese-foreign joint venture called Beijing Olympic Broadcasting.

Partnership and sponsorship agreements are also creating tensions before the Beijing games. The Olympic Partner Program allows companies to be worldwide exclusive partners with the IOC; Olympic partners have a more prominent marketing position and are distinct from BOCOG partners, Olympic sponsors and exclusive suppliers. They typically contract for four or eight years, covering two Olympics—the winter and summer games—or four Olympics. The cost of such partnerships is confidential.

Beijing Olympic partners include Coca-Cola, McDonald’s and Omega, none of which responded to repeated requests for contact for this article; Johnson & Johnson, which declined to be interviewed, stating that it has been involved in little legal work surrounding its partnership; and Kodak, Samsung and Visa, which also declined to be interviewed.

Chart Illustration by Jeff Dionise

AMBUSH MARKETING

Meanwhile, keeping a lid on ambush marketing—in which companies attempt to capitalize on the Olympics in ways they haven’t paid for—is a job overseen by Stupp, his four-lawyer staff and three lawyers at the IOC Television and Marketing Services SA in Atlanta, a wholly owned subsidiary that’s responsible for all IOC revenue-generating activity.

“We’re seeing a fairly higher than normal level of ambush marketing, not just by third parties but also by sponsors,” says Adam Mersereau, senior marketing counsel and head of business affairs at IOC Television and Marketing Services.

For example, if a bank sponsor were to use its Olympic marketing rights to promote its payment cards, whether they’re credit or debit cards, the bank would be committing sponsor-on-sponsor ambush marketing against another payment card sponsor that has purchased those rights.

“Sponsor-on-sponsor ambush is more common right now than in any games,” says Mersereau. It hasn’t been such a problem in the past because sponsors usually stay in their lanes.”

This will be Mersereau’s third Olympic Games, and he fell into Olympics work by chance when he was a fifth-year associate. “I got a call out of the blue from a guy who worked for the IOC who used to work at the law firm where my wife worked,” he says. “He was looking for someone he could trust to teach the strange Olympic framework to. I couldn’t resist the temptation. That was in 2003, right before the Athens games.”

Mersereau spends time educating sponsors on their rights. “When you get to technology companies like Lenovo and Samsung, that sector can get crowded, and we help them define the categories they can sell and how to run their [advertising] program.”

That, however, hasn’t kept sponsors from swerving into others’ paths. “You might have a sponsor who’s been sold the rights to one category of products also selling products in another category that’s been sold to another sponsor,” he says.

And resolving the problem has been more difficult than in past games. “Although the Chinese have shown sophistication in Western contract procedures, there’s still a higher level of relational engagement that’s required to solve problems,” says Mersereau. “With a Western company, you could quickly write a letter, quote the contract, send an example of the marketing, and it would stop. We’re noticing that there are usually high-level meetings and negotiations required to stop even something that seems completely clear-cut to us.”

Mersereau, however, is careful not to overstate the problem. “Most people have predicted chaos when it comes to intellectual property rights in China,” he says.

“That’s not been the case. The Chinese have shown an ability and a desire to learn and conform to the normal sponsorship and IP rights process. There are still frustrations, and sponsors are facing them regularly, but they haven’t materially detracted from the value of the sponsorship. Given the fact that China is a developing country in many ways and has had a bad history with IP rights, it’s going better than I’d have thought.”

Stupp agrees that these games have required personal and formal interactions. “Personal relationships can play an important role in contracts in Asia,” he says.

“The wording in contracts is, of course, very important, but sometimes there’s a certain bureaucracy that has to be respected. I’ve found my counterparts in BOCOG extremely helpful and very open, but when it comes to formalities, they have a certain process they wish to respect. You have to be sensitive to who at which level of the IOC is writing to whom at BOCOG. Sometimes it may take a little longer, but the job gets done.”

None of the attorneys report Chinese government control or interference in their activities. In fact, Stupp says the games may be pushing the nation’s leadership toward more flexibility.

“The Chinese government has been a little more open with, for example, freedom of the press, with respect to the reporting and broadcasting of the games,” he says. “I’d like to think having the games in China has helped matters progress in a way that there’s less bureaucracy.”

As for human rights concerns, attorneys say they respect people’s right to protest the China games, but that not all criticism is fair. “Most of [the Olympic partners] enter long-term sponsorship agreements, and a majority of them were committed to the 2008 Olympic Games before China was even selected,” says Mersereau. “They don’t choose to support the games because of where they are. They chose to support the Olympic movement as a whole.”

Stupp is disappointed in the way some protesters have expressed their opposition. “I understand people have issues with China, and the IOC appreciates and fully accepts that these people can make their points,” he says. “The torch relay provided a good platform for some of them to make their points. Where they went too far was when they forcibly interfered with the running of the torch. I saw one scene when they attacked a woman holding the torch in a wheelchair. That was a bit shameful.”

“We’re certainly aware of the human rights issues, and we understand the concerns addressed,” adds Dershowitz. “But it’s important to remember that the Olympic movement isn’t just about sports. It really is about bringing the world together and understanding and respecting cross-cultural viewpoints. That’s got lost in the press, and I hope we’ll get back to those issues.”

Now that he’s in the final stretch, Crabb is trying to leverage his experience on the Beijing Olympics into future work.

“In 2005, London was awarded the 2012 games, and I’d like to get some of that business,” he says. “It’s very political, and there are lots of great lawyers in the United Kingdom, but we have a London office and a lot of experience. I’m optimistic they might tap us on the shoulder.”

Howard Stupp.

Photo by AP Images/Rhoumela Cabanban

BEYOND BEIJING

The 2010 Vancouver Olympic Committee has already said it won’t hire non-Canadian firms, so Crabb has moved on to the first-ever Youth Olympic Games, which are set for Singapore in 2010. “They only have two years to prepare, where everybody else gets six,” he says. “The point we’re trying to make is that they need somebody to hit the ground running.”

Crabb has also been contacted about the 2010 Commonwealth Games. “We’ve been invited to join an Indian law firm to go through a tender process,” he says.

“The games will be in New Delhi in 2010, and organizers are just getting around to hiring international lawyers. I’m always looking for opportunities to get my name in front of other organizing committees.”

Looking at Crabb’s itinerary, you might think that one sweet perk of work in this area is the ability to travel the world and to witness—in person—athletes making history. But many attorneys involved in the games either don’t get perks, or are rather subdued about those they do receive.

“It’s a great honor for the firm to be granted the unique opportunity of providing legal services to BOCOG as its only Chinese legal counsel,” says Wang. “However, the firm is not regarded as an official sponsor for the Beijing 2008 Olympic Games, thus it is not entitled to any privileges or rights enjoyed by such sponsors. Attorneys who wish to attend the games will have to follow the ticketing procedures and rules made by BOCOG to the general public.”

Adam Mersereau.

Photo by Christopher Martin

Morrison & Foerster attorneys don’t get any special privileges, either. “They don’t have any expectations of getting anything,” explains Crabb, and that’s fine with him. “I go to Beijing about five times a year, and I’ve been to Lausanne. Don’t worry about me. I’ve been around.”

As for the games themselves, he adds: “I’m probably going to be at the games, but I’m not sure. If I’m required to be there, I’ll be there, but my work is related to the preparation of the games—and I have no delusions that the best seat is in front of your TV.”

Mersereau is excited but knows he’ll be working hard in China. “I’m at every Olympics for the entire time,” he says. “We’ll be in China for a month, and we can take our families. It’s quite an experience.”

The first two to three weeks are hectic with early morning to late-night work schedules, but then the craziness subsides, leaving Mersereau more time to soak up the Olympic experience.

“In many ways, it’s been a dream job,” he says. “It’s got travel, a unique subject matter, and the size and scope of the deals is large. There aren’t many jobs like it. I’m very grateful. I almost can’t believe it sometimes.”

Dershowitz is also enthusiastic about heading to the games: “I get to go—as in I get to—but I’m also there because if there’s a dispute about a medal or an issue that arises, we need to be prepared to respond.”

“From a personal perspective,” she says, “it’s been amazing to participate in, even just the lead-up. I don’t think I appreciated prior to joining the USOC how much of a peace movement the Olympics is and how it brings change and brings people together. I’m very excited to be a part of it.”

G.M. Filisko is a lawyer and freelance journalist in Chicago.