A Jury Rules Against the KKK

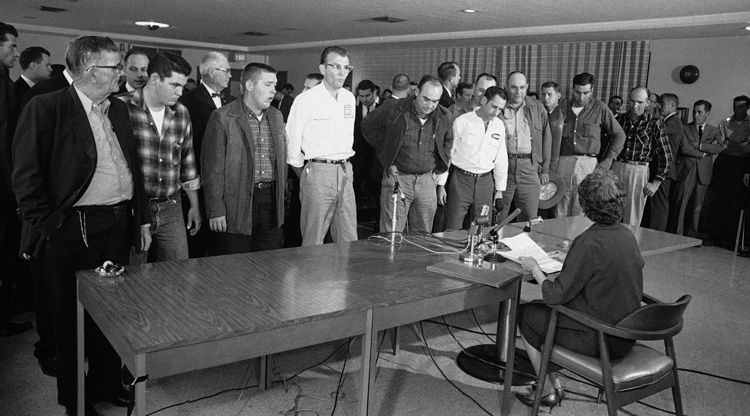

Eighteen defendants at their arraignment in the slaying of three civil rights workers in Mississippi. AP Photo

As an uneasy spring moved toward Freedom Summer in 1964, Mississippi was roiling. Civil rights initiatives were gaining momentum in the heart of Dixie; and the reaction was unsettling as scores of burning crosses forewarned of a reinvigoration of the Ku Klux Klan.

In Neshoba County, a voter registration initiative aimed to build black political participation and end a county legacy of violence and Jim Crow obstruction. The Council of Federated Organizations canvassed for volunteers at local churches, drawing the ire of Klansmen.

Michael Schwerner, a college student from New York City, had been highly visible in the registration effort; and the fact that he was Jewish drew special attention. On June 16, hearing that Schwerner might be at Mt. Zion United Methodist Church in the Longdale community, Klan members swooped in. But Schwerner was elsewhere, and they beat churchgoers and set fire to the building.

Foiled by circumstance, the Klan plot became more elaborate. On June 21, Schwerner and two others—volunteer and fellow New Yorker Andrew Goodman and James Chaney, a local African-American resident trainee—drove to Longdale to view the damage. On the way back, they were stopped in Philadelphia for an alleged traffic infraction. But it was a pretext to hold the three in jail while Klansmen—including members of the police and sheriff’s departments—gathered in darkness and in force.

Upon release, the three were heading toward Meridian on Mississippi Highway 19 when they were stopped again, shoved into a sheriff’s vehicle, carried to a desolated country road and shot dead. Their bodies were carted to the Old Jolly Farm and bulldozed into an earthen dam.

Local law enforcement declined to pursue the case, and the FBI moved in. After a burned-out COFO vehicle was found covered by brush, some 200 agents converged on Philadelphia. By the end of July, a search—tagged Operation MIBURN, short for Mississippi Burning—had not found the volunteers. They did, however, discover the bodies of eight African-Americans, including those of two students who had disappeared that May.

It was a tip that led the FBI to the Old Jolly burial site. And when local prosecutors again declined to pursue the case, a federal grand jury was convened.

In January 1965, the grand jury returned two indictments against 18 defendants, including three law enforcement officers—among them the sheriff of Neshoba County. One felony conspiracy indictment charged the men with violating the constitutional rights of Schwerner and the others under the Reconstruction-era Civil Rights Act. The other, a misdemeanor indictment, accused them of doing so under the color of law.

District Judge William Harold Cox, a Kennedy appointee and avowed segregationist who once derided black defense witnesses as “a bunch of chimpanzees,” dismissed the misdemeanor indictment against all but the three law enforcement officers. He dismissed the felony indictment entirely, arguing that the victims’ rights under the 14th Amendment did not apply. Federal prosecutors appealed. And in a unanimous March 1966 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed and remanded the case back to Cox, declaring his interpretation of the Civil Rights Act “bewildering.”

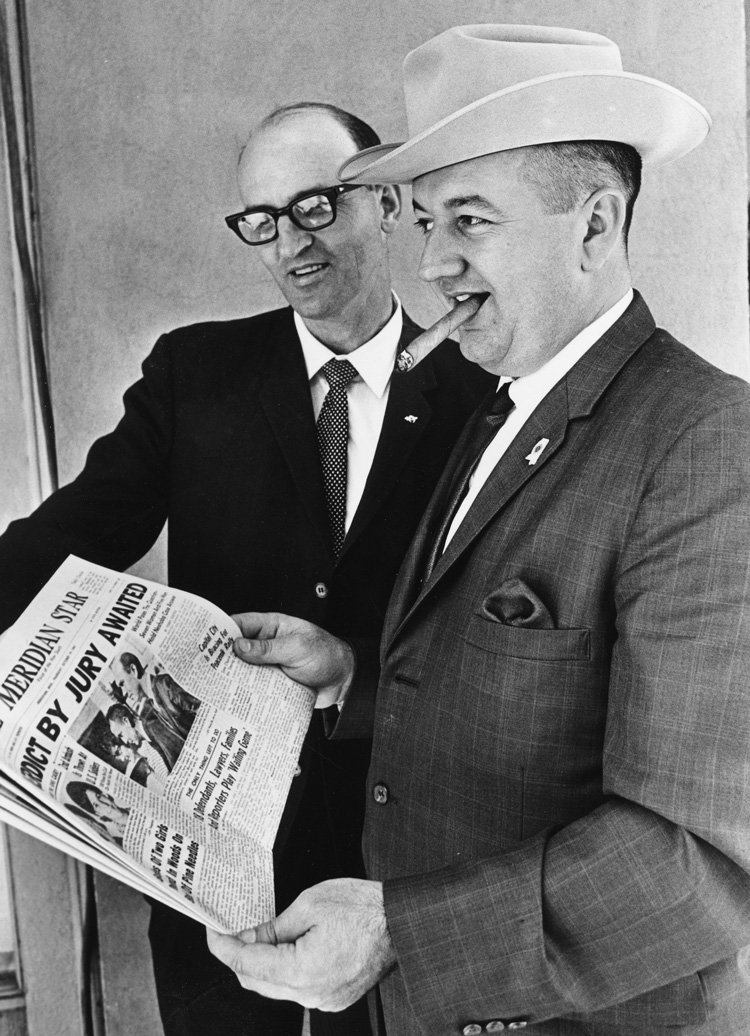

On Oct. 20, 1967, a federal jury convicted seven of the 18, including Cecil Price, the deputy sheriff who had been key to the abduction, and Samuel Bowers, the imperial wizard of the Mississippi White Knights of the KKK. They received sentences ranging from three to 10 years.

One of the key conspirators—Edgar Ray “Preacher” Killen—was released when a juror refused to convict him because he was a Baptist minister. However, Killen was retried and convicted in 2005 when new accounts emerged detailing his part in the conspiracy.

Co-conspirators Edgar Ray Killen and Cecil Price await the verdict. AP Photo