Underreporting makes notario fraud difficult to fight

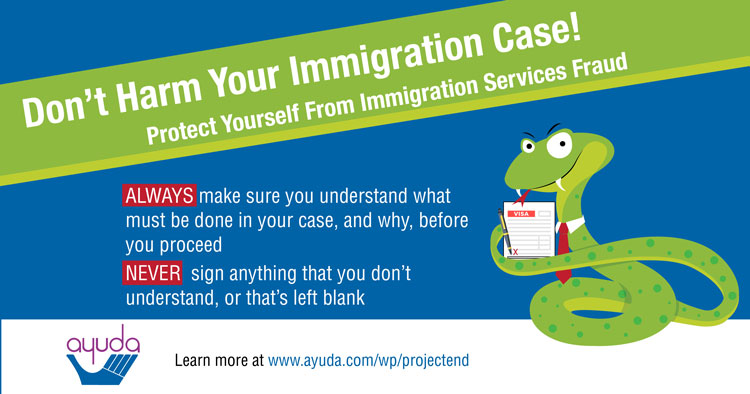

Photograph courtesy of Ayuda.com

If you need to understand a problem in order to solve it, lawyers who fight immigration legal-services fraud are in trouble. Accurate data is impossible to get, they say, because it’s extremely underreported.

There are lots of reasons for that. Because immigration law is complex and slow-moving, it can take victims months or years to realize they were cheated. When they do, they are often too embarrassed to come forward. When there’s no way to fix the damage caused by false lawyers, immigrants may not see the point of complaining. Those who end up in deportation because of a scam might have bigger problems.

And for people without legal immigration status, there’s also fear of being deported if they come forward, which advocates say is well-founded.

Though many police departments won’t share immigration information with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, reporting provides no legal immunity to deportation. The Trump administration removed an informal protection when it canceled an Obama-era policy against deporting immigrants who are exercising their legal rights.

See also: Increased enforcement of immigration laws has raised the risk of scams

As a result, Washington, D.C.-based immigration nonprofit Ayuda says there could be as many as 100 victims for every one who steps forward. In one case prosecuted by the Federal Trade Commission in 2011, authorities recovered 2,785 case files—but only 99 consumer complaints. That’s a reporting rate of 3.55 percent.

Tanisha Bowens-McCatty, associate director of the ABA’s Commission on Immigration, has been studying this problem, which she calls “the elephant in the room.”

In October, she led a panel on collecting fraud data at the ABA’s UPL School, a conference on fighting the unauthorized practice of law.

She says bar leaders there told her that immigration-related complaints have actually gone down—but nobody in the room thought it was because the problem has disappeared.

“You know, what’s the benefit for the victim?” she says. “In this current immigration climate, a big part of it is people are afraid to come forward.”

Photograph of Juan Manuel Pedroza courtesy of the World Justice Project

That’s why she’s working on finding a better way to collect that data. Nothing is ready yet, but she hopes to eventually develop better information or even a toolkit for immigrant advocates. That could help quantify the problem of immigration legal-services fraud and support her commission’s Fight Notario Fraud program’s mission of being a resource for advocates.

One potential solution: making victims of immigration legal-services fraud more comfortable coming forward.

Juan Manuel Pedroza, a PhD student in sociology at Stanford University, has studied what conditions might be helpful there.

After analyzing FTC complaints from different areas, he concluded that complaints tend to be higher where people have greater access to legal aid, as well as places where more Hispanic families receive food stamps. By contrast, he found that areas with more deportations and greater local support for Republican candidates had fewer complaints.

Most likely, he says, neither finding reflects actual rates of fraud. Rather, they likely show different levels of trust in government.

“What we do know is ‘Where is the tip of the iceberg feeling comfortable showing itself?’ ” he says.