Tracking down the ‘Craigslist Killer’

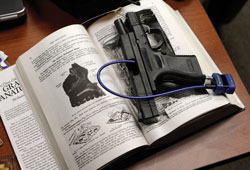

Philip Markoff hid the 9mm semi-automatic pistol used to murder Julissa Brisman in a hollowed-out copy of “Gray’s Anatomy.” AP Photo/Steven Senne

When police responded to the April 14, 2009, murder of a young woman in an upscale Boston hotel, they had little to go on. The victim was found face down in the doorway of her room, her hands bound with plastic ties, with three 9mm bullet wounds to the hip, lung and heart. They also found blood on the carpet, a spent bullet casing, a cellphone and a Gucci bag containing the identification of a 26-year-old New York woman named Julissa Brisman.

Within a week, though, police had their man: a 23-year-old second-year Boston University medical school student named Philip Markoff, who would soon become known as the “Craigslist Killer.”

The story of how they cracked the case, through a combination of lucky breaks, dogged police work, and a trail of traditional and digital forensic evidence, was told to a spellbound audience attending the ABA Techshow plenary session program “On the Trail of the Craigslist Killer: A Case Study in Digital Forensics.”

The co-presenters were Sharon Nelson and John Simek, president and vice president, respectively, of Sensei Enterprises, a digital forensics, information security and technology firm in Fairfax, Va. They walked the audience through the case step by step, from the discovery of Brisman’s body to Markoff’s suicide in jail while awaiting trial in August 2010.

It is a tale, Nelson said, of murder, bondage, robbery, betrayal and suicide that perfectly illustrates the interplay between digital and forensic evidence at the heart of a modern police investigation. And as Nelson spun out the tale, Simek slipped in lessons for lawyers who might seek similar access to the digital information—and for anyone concerned about just how much data is gathered on individuals, and how easy it might be for someone to get it.

Or as Nelson put it: “Whatever privacy we have is because of the sheer volume of electronic data. If you come to the attention of the government, from that moment on you have no privacy.”

SOLVING THE PUZZLE

Investigators got their first big break in the Brisman case when they turned on her phone, which was unlocked, and found a missed call from her friend Beth in Denver, who later told police she arranged trysts for Brisman, who was working as a masseuse for men she met through Craigslist ads. Beth said Brisman had a 10 p.m. appointment with a man going by the name Andy M. She gave police his phone number and email address.

Detectives caught another break when they secured hotel surveillance photos of a young man in a black leather jacket and a New York Yankees cap entering and leaving the hotel around the time of the murder. They showed the photos to another masseuse who had been robbed at gunpoint and bound with plastic ties at a nearby hotel by a man she met through a Craigslist ad four days earlier. She positively identified the man in the photos as the same one who had attacked her.

Within a few hours of Brisman’s murder, police found the Craigslist ads for both women. Before long (and with some FBI assistance), they learned that the phone numbers the man had used to communicate with the two women belonged to two prepaid, disposable phones that had been bought at an area store, and that the IP address for the email account he used to arrange his liaison with Brisman was registered to a man named Philip Markoff in suburban Quincy, Mass.

Two days after Brisman was killed, a woman working as an exotic dancer was attacked at a Holiday Inn Express in Warwick, R.I., by a man who had responded to an ad she had placed on Craigslist. Police identified photos of a man caught on the hotel’s security camera as the same man they were looking for in the Brisman murder.

Once they had the man’s name, police turned to Facebook, where they came across a wedding page created by Markoff’s fiancee, Megan McAllister, about their pending nuptials. Everything suddenly fell into place.

Police set up a stakeout of the couple’s apartment. And when Markoff went to a nearby grocery store, they followed—dusting everything he touched, including the handle of his grocery cart, to compare fingerprints with the one good print they recovered at the scene of the first attack.

On April 20, six days after Brisman was killed, police pulled over the couple’s car as they drove to a casino in Connecticut and arrested Markoff. Though McAllister kept insisting that Markoff was innocent, a search of the couple’s apartment turned up a treasure trove of evidence, including a 9mm semi-automatic handgun hidden in a hollowed-out copy of Gray’s Anatomy, a New York driver’s license in the name of Andrew Miller, bullets matching those used to kill Brisman taped to the back of a dryer, plastic ties, a stash of women’s underwear, a black leather jacket, a New York Yankees cap and a pair of brown leather shoes with Brisman’s blood on them.

Sixteen months later, on what would have been the first anniversary of his wedding, Markoff succeeded in his fourth attempt to commit suicide in jail by slashing the arteries in his neck and legs with a homemade scalpel he had fashioned from a pen and by stuffing toilet paper down his throat so he couldn’t be resuscitated if he was found alive. He had written McAllister’s name in blood on the wall of his cell.