Three Strikes: Litigation Section Drops Proposal for Guidelines on Dealing with Expert Witnesses

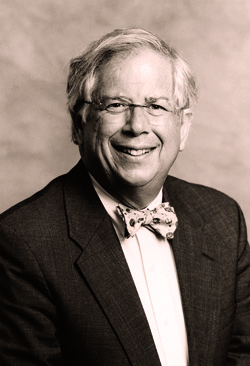

Lawrence Fox: “Nothing in the guidelines requires anyone to do anything. These are practical, commonsense, logical guidelines—nothing more, nothing less.”

It looks like the Section of Litigation’s idea for developing uniform guidelines that would apply to the retention and employment of experts in contested legal matters has struck out in the ABA’s policymaking House of Delegates.

In August, the ABA Guidelines for Retention of Experts by Lawyers failed to pass the House for the third time in just a year even though the section made significant changes in the format and scope of the guidelines.

After the latest debate on the proposed guidelines, it was apparent that not enough members of the House agreed with the Litigation Section that there is a need for standards—even voluntary ones—to address issues that arise when lawyers retain experts on behalf of their clients in cases that are litigated or otherwise contested.

“It’s a solution in search of a problem, and one that would create more problems than it would solve,” said Dwight L. Smith, a delegate for the Solo, Small Firm and General Practice Division, during the House deliberations at the 2012 ABA Annual Meeting in Chicago (where the House approved that new name for what formerly had been the General Practice, Solo and Small Firm Division).

In particular, Smith, a sole practitioner in Tulsa, Okla., cited concerns that the guidelines would add another layer of “pseudo-regulations” on lawyers already burdened by such things in other areas of their practices.

The odyssey that ended in Chicago began in 2010, when the Litigation Section created the Task Force on Expert Witness Code of Ethics to explore the possibility of creating a code of ethics for expert witnesses. The result was the proposed ABA Standards of Conduct for Experts Retained by Lawyers, which the section recommended to the House for adoption at the 2011 annual meeting in Toronto.

The proposed standards—which covered everything from integrity and professionalism to competence, confidentiality, conflicts of interest and contingency fees—were, the section said, an effort to create a uniform statement of what the relationship should be between experts and the lawyers who retain them on behalf of clients.

PHILOSOPHICAL AND SUBSTANTIVE OPPOSITION

In its report to the House, the section noted that, while many experts have ethics codes that apply to their professions, there are no uniform standards covering the retention and employment of experts by lawyers. As a result, the report stated, there were inconsistent expectations about the conduct of experts, unnecessary surprises that negatively affected the lawyer/client relationship, and disqualification motions challenging the conduct of certain experts.

If the standards were adopted by the House, the section planned to publish and disseminate them in the legal community. That way, lawyers could refer to the standards in their discussions with experts—and perhaps even incorporate them into their retention letters—in hopes of creating a common understanding between the expert, lawyer and client of what was expected from the expert in a case.

The proposed standards stated that experts should act with integrity and in a professional manner throughout an engagement, should not undertake an engagement unless they are competent to do so, and should treat any work product created or information received in the course of an engagement as confidential. The standards also said an expert should not accept an engagement that would create a conflict of interest without the client’s informed consent, and should not accept compensation that is contingent on the outcome of a case.

But the section’s proposal encountered heavy opposition in the House. On a philosophical level, opponents questioned whether the ABA should be in the business of setting standards that apply to other professions. And on a substantive level, opponents found fault with the format of the standards (which, with their black-letter statements and supporting comments, closely resembled the ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct) and their scope—which applied to all litigated matters, civil and criminal, including alternative dispute proceedings, commercial transactions and internal investigations.

In the face of that opposition, the Litigation Section withdrew its resolution. And over the next six months, the proposal was redrafted—at least in one key way. In the revised proposal, which came back to the House in February at the midyear meeting in New Orleans, the proposed standards had been changed to guidelines—but the guidelines themselves were virtually unchanged.

The new version picked up some support, primarily from the Tort Trial and Insurance Practice Section, which signed on as a co-sponsor. But opponents said the renamed guidelines still resembled the Model Rules. Critics also said that, while the guidelines purported to assist lawyers in dealing with experts, too many provisions focused on what experts should or should not do. The Litigation Section withdrew its resolution once again.

The section brought its third version of the proposal (PDF) before the House in August. This time, the scope of the guidelines had been narrowed to cover only litigated or contested matters in the United States or under U.S. law. Commercial transactions and criminal matters were excluded. The guidelines themselves were directed at the lawyer, not the expert. And explicit references to construing the guidelines with flexibility, common sense and a rule of reason were added in an effort to ensure that the wording didn’t cause unintended problems.

But when the matter came up on the first day of the session, it was quickly tabled for friendly amendments. The key change further limited the guidelines’ applicability to cover only testifying experts.

RISKS AND CONFUSION

When the matter came back before the House the next morning, Lawrence J. Fox, one of the Litigation Section’s delegates, tried his best to win over the opposition. He said the guidelines were essentially a set of best practices that lawyers would be free to follow or ignore as they see fit. “Nothing in the guidelines requires anyone to do anything,” said Fox, a partner at Drinker Biddle & Reath in Philadelphia. “These are practical, commonsense, logical guidelines—nothing more, nothing less.”

Fox’s views were echoed by Robert S. Peck, a delegate representing the Tort Trial and Insurance Practice Section. “These are simply a reference point” for lawyers who want to follow them, said Peck, who is president of the Center for Constitutional Litigation in Washington, D.C. “I’ve yet to hear anyone say that in an ideal world, they would not follow these guidelines.”

Leading the opposition was Ellen J. Flannery, a delegate representing the Section of Science & Technology Law. After ticking off a number of specific objections, Flannery, a partner at Covington & Burling in Washington, D.C., said, “In sum, we believe that these guidelines will provide little benefit but significant risks and points of confusion.”

Under his right to close, Fox expressed bewilderment at how strongly some opponents felt about the standards and cautioned against overreaction to them. Borrowing an image from the Cold War era, Fox said, “What we have here, I think, is a communist under every bed.”

But despite the entreaties of Fox and other supporters, the standards were defeated in a voice vote of the House that was confirmed by an informal head count. In the three times that the proposal came before the House, this was the only actual vote.

Afterward, Fox said the Litigation Section has no plans to bring the matter back before the House. But he said he still thinks that the guidelines could serve as a useful checklist for lawyers looking to hire an expert for a client matter, and that they might still be published in a section publication simply as “two people’s opinion”—meaning his and that of Jeffrey J. Greenbaum, a member of Sills Cummis & Gross in Newark, N.J., who chaired the task force that came up with the guidelines.