These lawyers battle in the boxing ring as well as the courtroom

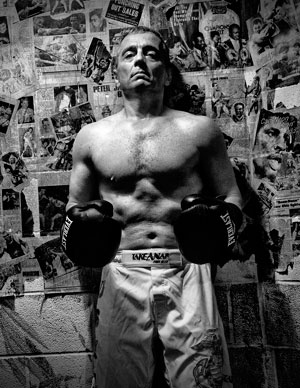

Manhattan assistant district attorney Matthew Bogdanos. Photograph by Len Irish.

So, too, has Manhattan assistant district attorney Matthew Bogdanos. “Boxing is like chess with 16-ounce gloves, ballet with headgear, and poetry with a left hook,” says Bogdanos, who has laced up the gloves as an amateur boxer and won all but three of his bouts.

To others, the lure of the sweet science instead bears the bitter taste of taking one right in the kisser. “There is nothing more shocking than getting hit in the face,” says Nashville, Tennessee-based attorney Stuart Scott, who sparred with professional boxers and competed in Toughman competitions, where novice amateur fighters could test themselves in the ring.

Lawyers are accustomed to the rough and tumble of courtroom arguments and of counseling irate clients, so they are no strangers to the sport. Mega-promoter Bob Arum graduated from Harvard Law School and worked in the U.S. Department of Justice in the 1960s before entering boxing as a promoter. Another boxing promoter, Lou DiBella of DiBella Entertainment, also has a Harvard law degree.But many lawyers do more But many lawyers do more than just promote. They get into the ring and substitute their knowledge of civil procedure for the intricacies of the Marquess of Queensberry rules.

Matthew Bogdanos. Photograph by Len Irish.

“There is a unique mentality to boxing,” says Topeka, Kansas-based criminal defense attorney Kevin Shepherd. “I felt very proud to have stepped into the ring as a professional boxer as many times as I did. A lot of it has to do with will. Oftentimes, will can overcome skill.”

He also describes what he calls the “warrior’s mentality,” a trait he possesses as a criminal defense lawyer. “You have to dare to win as a boxer and as a criminal defense attorney,” Shepherd says. “Oftentimes as a criminal defense attorney, the odds aren’t great. A court already has determined that there is probable cause for a prosecution, but you still try to win and you must not be afraid to lose.”

NOT JUST FOR MEN

Like Muhammad Ali’s daughter, Laila, who could also take a few punches, attorney Roseanne Beovich of Melville, New York, decided she was going to climb the ropes and get into the ring. “I wanted to be the first woman in my office to try it out,” says Beovich, already a competitive runner.

“The first time I sparred and was hit in the face, I was shocked,” she says. “It was an intense feeling and at first I didn’t like it. I actually almost quit. After I left the gym, I called my brother who has been a wrestler/mixed martial arts fighter his whole life and spoke to him about it. He told me that no one likes getting hit, and that I should use it as motivation to hit my opponent harder. After that, I didn’t mind it anymore. The next time I sparred I didn’t even feel the punches because I was too focused on punching my sparring partner back.”

Roseanne Beovich. Photograph by Len Irish.

She squared off against a more experienced opponent at the 2013 Long Island Fight for Charity event, which can be viewed on YouTube. Her family and friends were there.

“I’ve never experienced such an adrenaline rush in my life,” she recalls. “I was only in the ring about five minutes and it felt like five seconds. The arena was so crowded and loud, but I could only hear my brother, who acted as one of my coaches, screaming directions at me. It is an experience that I will never forget.”

Roseanne Beovich. Photograph by Len Irish

Beovich went the distance. “According to Fight for Charity, every fight is a tie, so we both got our hands held up at the end,” she says. “We did get our scorecards back and I lost, but my opponent is now a Golden Gloves fighter, so I don’t feel so bad about it.”

She says that she showed the lawyers in her firm that women can box just as well as men: “I think I proved to them that women can fight and they were both really impressed, or at least that’s what they tell me.”

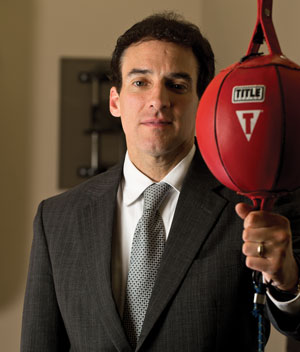

Scott, a member with the Nashville office of Dickinson Wright, where he litigates cases in family law, labor and employment and other areas, recalls his early years of boxing, which included competing in Toughman bouts.

“The mental toughness I developed as a lawyer helped me when I started fighting in Toughman competitions,” he says. Even though he was 36 years old (he is now 53) Scott entered numerous competitions. He had 15 bouts and won them all. But it was not without challenges, especially in his first fight. He was facing a younger opponent who didn’t seem to appreciate rules and customs.

“In my first fight, I went to touch gloves, a sign of courtesy and sportsmanship in boxing, and [my opponent] punched me in the face and knocked me down. I was mad, but I channeled my anger and kept my composure. I went all three rounds and won the fight by decision.”

The state of Tennessee later outlawed Toughman competitions, citing safety reasons, so Scott no longer fights in those bouts. But he still boxes at the local YMCA and trains people who want to learn the sport.

LEARNING TO PERSEVERE

When he first got into boxing, Scott, who still possesses a chiseled physique, was asked to serve as a sparring partner for a boxer who had an upcoming bout.

“It scared the hell out of me,” Scott recalls. “I sparred with him for eight rounds in one session. I was 35 years old at the time. I came home and looked in the mirror. I had a black eye and was sore in every part of my body from the waist up. I looked like crap, felt worse and thought about quitting. But, I didn’t. I stuck with it and became better.”

Kevin Shepherd. Photographs by Steve Puppe Photography.

Shepherd had about a dozen amateur fights and then turned pro in 1993, while he was a lawyer. He fought nearly 30 professional bouts in the heavyweight division. He had loved boxing as a youth growing up near Detroit.

When his grandfather took him to the bouts as a kid, he was hooked. “I saw Tommy Hearns fight in person when he was an up-and-coming fighter and he became a hero of mine,” Shepherd says. “Then, I saw his classic fight with [middleweight champion] Marvelous Marvin Hagler and I became a Hagler fan, too.” Hearns and Hagler waged war in 1985 in what many boxing fans call one of the greatest fights ever. It is known as “the Eight Great Minutes” because it ended in the third round.

Manhattan ADA Bogdanos, meanwhile, is a modern-day hero and Renaissance man. A colonel in the U.S. Marine Corps Reserve, Bogdanos served six tours of duty since September 2001, investigated the looting of the Iraq National Museum, and won the National Humanities Medal in 2005. He has also authored the memoir, Thieves of Baghdad: One Marine’s Passion for Ancient Civilizations and the Journey to Recover the World’s Greatest Stolen Treasures. Now he prosecutes homicides.

But Bogdanos also has a deep passion for the sport of boxing. He has organized a boxing charity event called the Battle of the Barristers. All the proceeds go to charity and most of it to the Wounded Warrior Project, assisting veterans wounded in the service of their country.

“Boxing always had an appeal to me from a classical standpoint of a pure sport with an extraordinary lineage,” he says. Bogdanos remembers walking into the famed Gleason’s Gym—a world-renowned boxing gym in Brooklyn—as a teenager and seeing posted on the gym’s wall the quotation from the poet Virgil: “Now, whoever has courage, and a strong and collected spirit in his breast, let him come forward, lace on the gloves and put up his hands.”

Bogdanos remembers fondly the lessons of his first trainer, ex-boxer Sammy Morgan, who always told him: “Keep it simple.” He says that “simplicity and fundamentals were lessons that I later carried over in combat and in the courtroom.”

GETTING ‘SMOKED’

In the 1990s, Bogdanos returned to boxing and participated in several “smokers” —unsanctioned boxing events—for the New York City Police Department. In his first fight, there were about 2,000 cops in the audience. He got knocked down five times but finished the fight on his feet and went the distance.

Many years later, Bogdanos was in a bar with some friends and had an epiphany. “I remember talking with another prosecutor who was a former boxer and another who was a former Marine,” he recalls. “I mentioned about the smokers for the police department and we thought: ‘Couldn’t we do something like that to benefit wounded veterans?’ “

Bogdanos was appalled at the number of veterans coming home with lost limbs and other injuries from the war in Afghanistan and other places. “When I connected with the Wounded Warrior Project, I knew we had a charity we would support.”

He got the support from District Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr. “Clearly, this was not an official, DA-sponsored event, but I wanted his support,” Bogdanos says. “He asked all the right questions, including questions about proper medical care and safety precautions, and then gave his approval.”

The result has been four stagings of the Battle of the Barristers, held each April. The first one raised $50,000; the second $65,000; the third $86,000; and this year’s raised more than $120,000. Bogdanos has fought in every event, including last year at age 58.

“This is a team effort and a team concept,” Bogdanos says. “We had 50-plus volunteers from the DA’s office who worked the show. We had 60 people willing to step into the ring to fight, though we could only match up 26 of them properly. I’m proud of how this office comes together to support this event. It is a shared experience.”

RINGSIDE JUDGE

Montvale, New Jersey-based attorney Steve Weisfeld practices commercial transactional real estate with the law firm Beattie Padovano. He is not a judge in the legal sense of the term. But in the boxing world, Weisfeld is one of the sport’s elite judges.

In professional boxing, bouts are scored by three judges who sit at ringside and must exhibit concentration in the face of crowd noise, pressure and lightning quick punches thrown in the ring by trained professionals. Weisfeld has judged about 80 world championship bouts, including the April heavyweight title bout between champion Wladimir Klitschko and challenger Bryant Jennings.

Weisfeld loved the sport as a youngster, watching the likes of Ali, Hagler and Sugar Ray Leonard. He also would score the fights at a young age.

He started judging amateur bouts in 1986 and kept doing so while attending Cornell University Law School. He then judged his first professional bout several years later in 1991.

Steve Weisfeld. Photograph by Arnold Adler.

During his career as a professional boxing judge, Weisfeld has scored bouts involving such world champions as Manny Pacquiao, Juan Manuel Marquez, Carl Froch, Bernard Hopkins, Miguel Cotto, Vernon Forrest, Antonio Tarver, Félix Trinidad and George Foreman.

For his professionalism and accurate scorecards, he has earned the respect of the boxing world. In 2009, Weisfeld earned induction into the New Jersey Boxing Hall of Fame. “It was a tremendous honor, especially with my family and friends in attendance.”

Like the other lawyers, Weisfeld sees the companion skills in both boxing and legal practice, including courage, concentration, preparation, mental toughness and the ability to respond quickly in times of duress.

“I agree that concentration is an important ability in both the practice of law and judging a boxing match,” says Weisfeld. “Other similarities are impartiality, confidence and experience. I do transactional commercial real estate work at my law firm. Even when I am advocating for a client, I still need to take into account whether my proposal is fair and how it will be received by the other side.”

Steve Weisfeld. Photograph by Arnold Adler.

“In both judging and the practice of law, you must have the confidence in your own opinions,” Weisfeld elaborates. “Finally, like anything in life, you get better by experience. I believe that I am better both as a lawyer and a [boxing] judge now than when I started both approximately 25 years ago.”

“There are several similarities between boxing and litigation,” Scott says. “Just like litigation, preparation is everything for a fight. In law, you must take the time to conduct proper discovery, develop legal theories and prepare for different arguments. You also have to be flexible and fluid in your approach to litigation. In boxing, you also have to be very prepared. You must be fluid and flexible in the ring. You can’t fake a fight. You must have a game plan and you must have the ability to adapt to different circumstances as they present themselves.”

Scott also carries lessons he learned from boxing into his legal practice. “I have found that practicing domestic relations law is also similar to boxing in that you must never allow yourself to be mentally taken out of your game plan.”

Topeka attorney Shepherd agrees that being thoroughly prepared is absolutely vital in both arenas. “You must prepare before stepping into the ring or the courtroom,” he says. “If you are not prepared and well-read on the governing law and haven’t filed the proper motions, you are not going to do well.

“Likewise, in boxing if you haven’t sparred enough rounds, you are not ready to step into the ring. In both boxing and law, you also must have a good strategy.”

Shepherd practices all types of criminal defense, but he focuses much of his attention on DUI defense. “I’ve always rooted for the underdog,” he admits. “That is part of what attracted me to both boxing and to criminal defense.”

He also still has urges to return to the ring even as he ages. “I’m 45 years old and have had two shoulder surgeries, but I still possess that warrior’s mentality. I still work out in the gym, but it is hard to get as motivated as I was when I had a fight on the horizon.”

NO ONE ELSE TO BLAME

Bogdanos says another similarity is that in both boxing and lawyering you are often alone: “There is no one to blame but yourself when you are in the ring facing your opponent or arguing in front of a jury.”

He identifies “the rule of being prepared, the rule of being honest, the rule of comporting yourself with dignity and the character trait of courage” as necessary attributes to being successful in the ring and in court.

“Another similarity is the speed of response required,” Bogdanos says. “In boxing, you must process information quickly in the ring and respond to your opponent. You must be able to read your opponent, such as noticing by his muscle twitches whether he is going to throw a jab or hook.

Stuart Scott. Photograph by David Mudd.

“The same principle applies in the courtroom, where you must be able to read where the defense is going, read your witnesses and read the judge.”

But many of the practitioners emphasize that a good boxing workout—punching the heavy bag, working the speed bag, jumping rope and other boxing-related drills—can provide a much-needed respite from the demands of law practice.

Bottom line: It provides a great form of exercise and can be quite a relief from the stresses of law practice.

“Boxing is a huge stress relief, especially after a hard day at the office,” Beovich says. “The fact that I could take my stress out on the bag, the mitts or a sparring partner really helped. My trainers actually used to tell me that I should come train after a hard day because I would hit harder.”

Beovich handles guardianship proceedings and estate litigation, often between family members. It can be quite contentious. “Since I deal with a lot of fighting all day, every day, boxing was a great way to channel the stresses of dealing with these types of cases.”

“You have to be dedicated and work extremely hard to be a boxer,” she says, “just like being a lawyer.”

This article originally appeared in the October 2015 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “The Allure of the Sweet Science: Lawyers know the rough and tumble of the courtroom, so they understand the beauty of the uppercut and the cross punch.”

Regular contributor David L. Hudson Jr. is a licensed boxing judge, the co-author of Boxing's Most Wanted: The Top 10 Book of Champs, Chumps and Punch-Drunk Palookas and the author of Combat Sports: An Encyclopedia of Wrestling, Fighting, and Mixed Martial Arts and Boxing in America: An Autopsy.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.