The Toughest Call

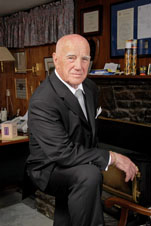

Frank Armani. (Photo by Dave Revette)

Most lawyers are unlikely to recognize Frank Armani by name, but they’re probably familiar with his story.

Armani is one of two upstate New York lawyers who in the mid-1970s became embroiled in an agonizing test of a lawyer’s duty to maintain client confidences under some of the most trying circumstances imaginable.

It was the summer of 1973. Armani and another lawyer, Francis Belge, had just been appointed to represent Robert Garrow for the murder of Philip Domblewski, an 18-year-old college student who was camping in the Adirondacks with three friends when Garrow attacked them and tied them all to trees. His companions escaped, but Domblewski didn’t.

In the course of debriefing by his lawyers, Garrow admitted killing Domblewski. But there was more. He told his lawyers that, in a separate incident, he had murdered another camper—and abducted, raped and murdered the man’s female companion. Garrow also admitted that he had abducted, raped and murdered a 16-year-old girl. Garrow even told his lawyers where he had dumped the bodies of his two female victims—information they confirmed by photographing the remains at the locations he had identified.

DEEP SECRETS

The lawyers told nobody about their client’s confession; nor did they reveal that they had located the bodies of his two missing victims—even after the father of one of the victims begged them for information about the fate of his missing daughter. And even after the victims’ bodies were accidentally discovered several months later in separate locations hundreds of miles apart.

Armani and Belge, who died in 1989, kept their client’s secret for nearly a year. But during his trial in 1974, under direct questioning by Belge, Garrow confessed to murdering Domblewski, the other male camper and the two women who had been missing, as well as to a number of rapes and abductions throughout upstate New York. The day after Garrow finished testifying, Armani and Belge acknowledged publicly that they had known all along about the murders and the locations of the victims’ bodies.

Garrow was convicted on one murder charge and sentenced to 25 years to life in prison. He was shot to death by police in September 1978, shortly after making a daring prison escape. Ensuing editorials expressed no mercy for Garrow. The Poughkeepsie Journal called him “a malignant cancer on the society that fostered him” and “less than useless to the human race.”

Armani and Belge, who both practiced in Syracuse, received widespread support from the legal profession. But in the court of public opinion, they didn’t fare much better than their client.

While the two lawyers insisted that their duty of client confidentiality obliged them to remain silent, they were widely reviled outside the profession for withholding the information. Their once-thriving law practices withered. They received hate mail and death threats.

Longtime friends stopped speaking to them. They had to move out of their homes. Belge eventually gave up his law practice altogether, while Armani slowly rebuilt his.

A grand jury investigated both men, ultimately indicting Belge, who had been alone when he found one of the bodies. He admitted moving the remains to get a better picture and was charged with failing to report a dead body, then failing to provide it with a decent burial. On the day the grand jury announced its decision, Armani suffered a heart attack.

(Charges against Belge were dismissed in 1975 by the trial court judge, who lauded Belge for the zeal with which he had protected his client’s rights. People v. Belge, 372 N.Y.S.2d 798.)

The parents of one victim filed an ethics complaint against the two lawyers with state bar disciplinary officials. It took four years, but that complaint too was eventually dismissed. In its decision, the Committee on Professional Ethics of the New York State Bar Association said the assurance of confidentiality helps encourage proper representation, which requires full disclosure of all relevant facts by the client—even if those facts include the commission of prior crimes. Opinion 479 (1978).

A HERO’S WELCOME

Armani, now 79 and semiretired, is widely regarded within the legal profession as a hero. In 2006, he received a distinguished-lawyer award from the Onondaga County (N.Y.) Bar Association. This year, he was nominated for the Michael Franck Award presented by the ABA Center for Professional Responsibility. And in early June, Armani received a standing ovation when he appeared at a program about the Garrow case at the center’s National Conference on Professional Responsibility, held in Chicago.

Experts say the case offers a particularly stark, compelling example of one of the most difficult ethical dilemmas to confront a lawyer. The case is still taught widely in law schools, and it has been discussed and dissected in countless law review articles, books and court opinions. The case was even the subject of a book titled Privileged Information (co-written by Armani) and the basis for the 1987 feature film Sworn to Silence.

Law professor Lisa G. Lerman, who got to know Armani while researching his case for a textbook she co-authored in 2005, likens him to Atticus Finch, the noble small-town lawyer who takes on an unpopular client in the novel To Kill a Mockingbird.

“The difference is that, unlike Atticus Finch, Frank Armani is a real person,” says Lerman, who teaches at the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. She nominated Armani for the Franck Award.

Lerman said at the program about the Garrow case that she doesn’t have many heroes who are lawyers. “But if I had to make a list, you’d be right up there at the top, Frank,” she said.

Thomas D. Morgan, a law professor at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., says Armani is a heroic figure in the sense that he faced a series of very difficult choices and ultimately came to the right conclusion.

“This case is not just an interesting historical footnote,” says Morgan. “It’s a central case in our development and understanding of what it means to be a lawyer.”

NO SECOND THOUGHTS

Morgan and other experts say the case still is relevant to the ongoing debate over the boundaries of a lawyer’s duty of confidentiality to clients. In the ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct, that duty is set forth in Rule 1.6. (The Model Rules are the basis for conduct codes that directly govern lawyers in most states.)

At the time Armani and Belge represented Garrow, lawyers in New York were governed by that state’s version of the ABA Model Code of Professional Responsibility. The Model Code allowed a lawyer to reveal “the intention of his client to commit a crime and the information necessary to prevent the crime,” but not prior acts admitted in confidence.

The Model Code was replaced by the Model Rules in 1983; in its original version, Rule 1.6 allowed a lawyer to reveal client confidences “to prevent the client from committing a criminal act that the lawyer believes is likely to result in imminent death or substantial bodily harm.” In 2002, Rule 1.6 was amended to permit a lawyer to reveal confidential information “to prevent reasonably certain death or substantial bodily harm.”

While those differences in language might seem like ethical hair-splitting, the 2002 amendment was one of the most hotly debated items in a package of Model Rules revisions considered by the ABA House of Delegates. The House narrowly adopted the new language over objections that it would erode confidentiality rules for lawyers. Other proposals by the Ethics 2000 Commission to ease the rules on confidentiality were voted down or withdrawn in the face of opposition.

(A year later, the House revised the Model Rules to allow lawyers to reveal client confidences to prevent financial wrongdoing in some circumstances.) Armani said at the CPR program that in 1973 he wasn’t even aware there was a written ethics code for New York lawyers. His guide was the oath he had taken when he was sworn in as a lawyer in 1956. He had promised, he said, to “maintain the confidence and preserve inviolate” the secrets of his client. And that was what he and Belge did.

Armani insists he is no hero. And he says he would handle the Garrow case just the same if he had it to do over again.

“Of course,” he says. “I’d have to.”

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.