The ‘Super Median’

When new clerks asked justice William J. Brennan how the U.S. Supreme Court shaped the law, Brennan was known to raise one hand with his fingers splayed.

Five—that was the answer. Five votes on a nine-member court would carry the outcome.

Justice John Paul Stevens was a student of Brennan’s mathematics. Stevens mastered the court’s calculus with but a single goal: Get Justice Anthony M. Kennedy on Stevens’ side of the equation mark.

In a court with entrenched conservative and liberal wings, Kennedy, a moderate Republican, has been the man in the middle. And with seniority on the left, Stevens enticed a wavering Kennedy, allowing him to write majority opinions or luring him by including his arguments in other cases.

But with Stevens retiring, a Democratic president and Senate face the question of how to achieve a five-vote advantage that means controlling the future of constitutional law.

They hope to do so with Solicitor General Elena Kagan, nominated to succeed Stevens. A former Harvard law dean, Kagan is praised for energizing the school and bringing aboard an ideologically mixed faculty.

“She did a good job of bringing in people from a variety of backgrounds and viewpoints, and getting them to get along with one another,” says David Stras, a University of Minnesota law professor. As for consensus building, “I don’t think any justice can come on the court and do that the first four or five years. … It’s a very high learning curve.”

Such was the art and practice of Stevens, whom Harvard law professor Richard Fallon called “a wily practitioner of coalition politics.”

But on this court, even the most nimble liberal justice may find corralling Kennedy a rough ride. Nor, say experts, do they expect the other three justices—Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen G. Breyer and Sonia Sotomayor—to replace Stevens’ diplomatic ken.

“A reputation as a centrist is crucial to influencing Kennedy because I think that is how he perceives himself,” says constitutional law professor Kenneth M. Murchison of Louisiana State University law school. “But the personal qualities associated with being a consensus builder might be even more important.”

Either way, it’s a tall order. Rarely, observers say, has there ever been a situation on the court with a stronger center judge. For years, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor and Kennedy shared the ideological middle. If a litigator couldn’t get O’Connor, then she went for Kennedy.

But after O’Connor retired in 2005 the court’s center opened up, leaving Kennedy alone.

“He’s the most important central justice there has been, especially for this long a time. I can’t identify anyone who has held that spot for a longer time,” says Murchison.

Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr. was influential in the late 1970s, “but not nearly as extensive” as Kennedy, says Murchison, author of the 2009 article “Four Terms of the Kennedy Court: Projecting the Future of Constitutional Doctrine.”

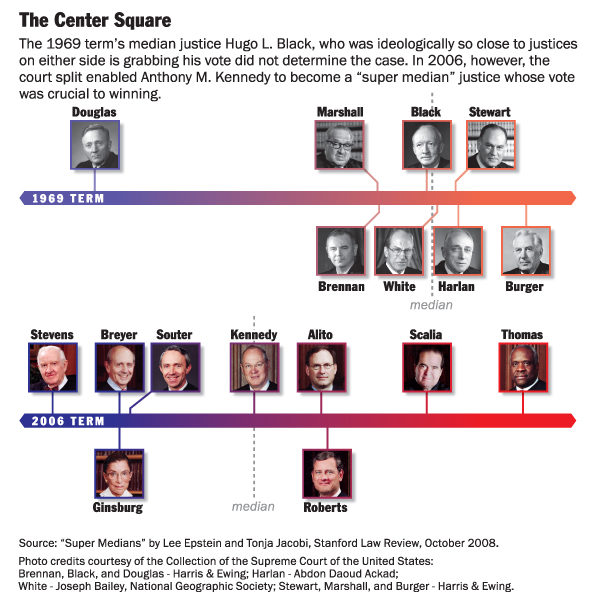

In fact, Kennedy’s role the last few years has surpassed merely being the median judge. He has become a “super median”—the decisive central judge that neither side can do without, according to Northwestern law professors Lee Epstein and Tonja Jacobi.

Just as some describe super precedents such as Roe v. Wade, or super statutes like the 1964 Civil Rights Act, so, too, are there super medians. Each has endured and shaped doctrine around them.

“Coalitions could be called in lots of different ways,” Epstein says. “Now you pretty much need Kennedy.”

Other courts also have had median justices, but the ideological concentration of nearby colleagues diminished the median’s weight in dictating the outcome. The majority might form around other justices with similar ideologies if need be.

But the policy gap between Kennedy and the justices on either side of him is wide enough to keep him starkly in the middle, Epstein and Jacobi’s research shows. Nor is there any overlap on policy issues for other justices to share Kennedy’s moderate range.

“This current court is going to be about as conservative or about as liberal as Justice Kennedy,” said Solicitor General Paul D. Clement in 2007.

SINGLE-VOTE EVIDENCE

The arrangement has placed this Supreme Court in a historic position. “That gap is fairly extraordinary,” Epstein says. “It tells you what an odd historic court we have right now, with Kennedy controlling it.”

The situation is revealed vividly in single-vote cases, where the court usually splits like a tug-of-war, with liberals (Stevens, Breyer, Ginsburg and former Justice David H. Souter) on one side, and conservatives (Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., Antonin Scalia, Samuel A. Alito Jr. and Clarence Thomas) on the other.

Since 1953, Kennedy has joined the most single-vote majorities in three of the top four terms in which the median voted with the majority, Epstein and Jacobi show. Mean while, in the 2006-07 term, Kennedy joined every single-vote majority—the only justice since 1953 to do so. In 5-4 cases, he voted with the four conservatives in 13 cases, or 54 percent; and with the four liberals in six, or 25 percent.

Over that term, Kennedy voted with the minority in two cases—the smallest number. Stevens, meanwhile, led minority voting in 25 cases, a signal of his place as the senior justice on the left wing.

In the 2007-08 term’s 12 cases that split 5-4, Kennedy joined the liberals in four and the conservatives in four.

But the 2008-09 term mirrored the figures of 2006-07: Of 23 cases ending 5-4, Kennedy joined the conservatives in 11 (48 percent) and the liberals in 5 (22 percent).

It’s not hard to pick out Stevens’ sway in grabbing Kennedy. For example, in 2007’s Massachusetts v. Environmental Protection Agency, Kennedy cast the fifth and deciding vote with the court’s liberal faction to reject President George W. Bush’s policy of regulatory inaction on global warming.

At oral argument, Kennedy cited a 1907 precedent that appeared in none of the briefs. In Georgia v. Tennessee Copper Co., the state objected to air pollution wafting over its territory, and Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes agreed it could sue to protect its independent and quasi-sovereign interest “in all the earth and air within its domain.”

In his majority opinion, Stevens used Tennessee Copper to say Massachusetts and other states indeed had standing to protect themselves from the impact of global warming.

Stevens and Kennedy also teamed up that term when the court initially denied two cases involving inmates at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Although three justices voted to decide whether the courts should hear inmates’ claims for habeas corpus, the court couldn’t garner the fourth vote to grant cert.

In a joint memo on Boumediene v. Bush and al Odah v. United States, Stevens and Kennedy said Gitmo lawyers needed first to exhaust all the available remedies in the law. Observers say the move was key in making sure the liberal wing had Kennedy on its side.

In the end, the court took the cases. Stevens wrote al Odah; Kennedy, Boumediene.

FORWARD MOTION

So far this term the two justices have disagreed in two key cases. In Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, Kennedy wrote the majority, tossing out limitations on corporate campaign contributions, while Stevens’ 90-page dissent read like a valedictory on stare decisis and disregarding Congress, among other woes.

Meanwhile, in Salazar v. Buono, Kennedy again led with a plurality opinion that overturned a lower court ruling ordering the removal of a cross from a World War I mem orial in California’s Mojave National Preserve. Meanwhile, Stevens wrote that he and the minority justices opposed such displays.

The cases may foretell the court’s future: Even with a new face, Ken nedy will stay in the pivot. But how the court will align on other issues coming its way—election law, the new health care statute, immigration and terrorism law—will arise soon enough.

Among the questions is whether Kagan, assuming her confirmation, will keep to her left-centrist thinking. “We know that justices move ideologically when they get to the court,” Jacobi says.

Also, without Stevens, if Kennedy sides with the liberals he would have seniority.

“It might be interesting to see if Kennedy can get [the liberals] to come closer to his position,” says Murchison. But, he adds, “that doesn’t mean Kennedy’s vote will be easy to predict.”