The Rise of the Latino Lawyer: New Study Reveals Inspiring Successes, Lingering Obstacles

Editor’s note: This article, though anecdotal in narrative, is based on an in-depth study of Latino professionals in Washington state involving interviews and detailed surveys of personal histories from a scientific sample of 102 Latino lawyers. Washington’s Latino population closely resembles that of the greater U.S., and includes immigrant populations from Cuba, Mexico, Puerto Rico and virtually every country of Hispanic culture. The study is detailed in book length in Everyday Injustice: Latino Professionals and Racism by Maria Chávez.

There are dozens of different reasons why someone would choose to go to law school and become an attorney. Some may want to go into politics or trial work. Others may want to work for social justice, a nonprofit or a cause they are passionate about, such as the environment. Some view it, like many others, as a stylish path to making money. But many want a challenging profession with the rewards that can bring, both personally and financially. Some are influenced by parents or by lawyers they have known, or even by an experience they have had with the law. The judiciary or corporate practice or public defense or child protection advocacy—all the varied uses of a law degree beckon thousands of people each year to apply for law school to eventually become attorneys. For some, however, the motivation that drives them to become attorneys is a bit different, motivated by a sense of feeling they have experienced wrongs in their lives. For many Latinos, the decision to become a lawyer can be very personal.

Photo by ©Keith Brofsky/www.fotosearch.com

Also see: Stephen Zack: Ignoring Obstacles.

This was the experience for Anna, who grew up the youngest daughter of Mexican immigrants who earned a meager living as farmworkers in Burley, Idaho. As Anna recalls the experiences that motivated her to go to law school, she notes they weren’t all pleasant. She hated that her parents weren’t treated fairly when they worked in the fields of sugar beets, beans or potatoes. She recounts the grueling, often illegal, conditions they endured in the fields. But it is the smaller indignities that seem to weigh heaviest in her memory. Recalling them, she begins to cry. The toilet paper they carried because no sanitation facilities were provided. Fifteen-minute lunch breaks imposed by the farmers, reduced to 10 minutes by her father, who feared trouble for taking time for any lunch at all.

Her dad was always especially cautious when it came to the ranchers or bosses because he had no power and no conception of having rights. And it was his experience—her family’s experience—that made her decide to go to law school.

It wasn’t easy for her. There were many obstacles along the way. While she was an undergraduate, Anna’s political science professor at the university said she’d never make it as a lawyer. He told her directly that she didn’t have what it takes. Yet, in 2009, she won a prestigious pro bono award from a large urban bar association—an award usually reserved for attorneys from big firms, not for lawyers in solo practice who devote themselves to helping undocumented workers collect the wages they are owed.

Illustration by James Steinberg

TURNING ANGER INTO ENERGY

Feeling wronged is also what drove Tony, a man now in his late 50s, to become a lawyer. His high school teachers suggested that he set his sights on becoming an auto mechanic. This made him so angry, he recalls, that he was determined it was the last thing he would become. Perhaps they thought that by guiding him into a trade, they were actually doing this young Latino a favor. And in a way they did.

Their tracking and discouragement provided Tony with the motivation he needed to join one of the most prestigious professions in America. He states, “As a Latino or Native American or any kind of minority, you’re just another wetback, or you’re just another migrant farmworker or whatever, until you are a professional; and that suddenly changes your stature, and you have to be aware of it whether it’s been brought out to you or whether you’ve faced it or you’ve experienced it—it’s there. … [The] whole idea of being a minority and working as a professional, you almost have to be outstanding in order to be accepted.”

For one young Latina, Eva, who was raised in a family plagued by alcoholism, domestic violence and psychological abuse, she just wanted a life that was going to provide her with the skills and the means to successfully raise her young daughter on her own, and to leave the dysfunction of her upbringing far behind them. Eva became a single parent as an undergraduate, and she knew she needed a career that would bring financial security for her and her daughter; so she chose to follow law as a sure path to that kind of success.

Eva opened up her own law practice after years of struggling in law firms or working for other people. She now runs one of the largest and most successful woman-owned law firms in her city, and the largest owned by a woman of color. In 2009, she was appointed to the city council, the first Latino member in a Northwestern city that is more than 50 percent Hispanic. An acknowledged expert on gang problems, Eva remains active on boards and has started a neighborhood association in a gang-entrenched area. Her efforts to combat gang violence are mostly focused on turning Latinos toward education and away from the streets.

BALANCING TWO WORLDS

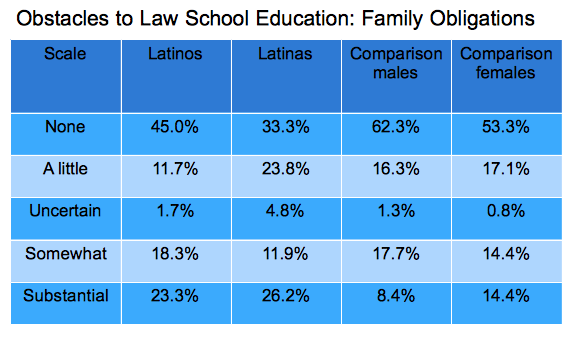

Anna, Tony and Eva were respondents to an in-depth research project, the first such look at the sociology of Latino lawyers. Each had different reasons and different obstacles to overcome to become lawyers, but their experiences reflect those of the scores of Latino lawyers surveyed. Typically, they are second-generation Americans who have had to balance two worlds. They pursued membership in one of the most prestigious and powerful professions in America and simultaneously tried to maintain their cultural roots by speaking Spanish and helping out in the Latino community. The majority of their parents lacked high levels of formal education—many didn’t even have a high school diploma. Most of their fathers came to the United States and worked as manual laborers or blue-collar workers. They understand at a very personal level how education changes lives.

For example, this quote from one of the Latina respondents is very representative of the experiences of the Latino lawyers I interviewed:

“I made it to an elite college because I was intellectually curious and knew that education would open up a world of possibilities for me—would provide me with opportunities and information that my parents had not had. My mother only has a fifth-grade education. My father never attended school at all. I was adventurous and ambitious, and I had no idea that I would be in competition with middle-class and wealthy classmates who had been preparing for elite universities since they were 5. I had never heard of the elite prep schools from which my classmates at Yale graduated, and I had no idea that high school students actually took courses to improve their SAT scores. I also had no idea how much money an elite education would cost. Paradoxically, my family’s poverty worked to my advantage. As a consequence of generous financial aid—for which I will always be grateful—I was able to graduate from college with virtually no debt.”

This Latina acknowledges how much her legal education changed her, but she was also politically astute enough to know that as a Latina, if she was going to make a difference, she would have to have the right credentials. She said, “By the time I applied to law school, I had become highly politicized. I wanted to use law to make a difference in the world, and I knew that I [as a Latina] would not be taken seriously unless I attended a top law school.”

Photo by Corbis Images

REFLECTING ON RACISM

By any measure, Latino lawyers are atypical: The latest U.S. census figures show that Latinos now account for 16 percent of the U.S. population, but only 4 percent of its lawyers.

The Latino lawyers in my study represent true success stories—they are the cream of the crop from the largest ethnic and racial minority group in the country. In their educational, financial, professional and civic successes, as demonstrated by survey data, their stories also represent the classic immigrant rejection story endured by nearly every new immigrant group from our founding to the present. Whether that group was German—whose large numbers of immigrants worried Benjamin Franklin—or Irish, Italian, Polish, Asian or African, history suggests that many Americans found a reason to discriminate. However, many Latino lawyers say they, like other Latinos, have remained racialized in the eyes of many, regardless of how long they have been here or whether or not they are citizens.

One of the main findings in my study is that Latino lawyers still face an astounding amount of racism and discrimination in their professions and in their communities. This experience does not end once Latinos have become professionals. My study demonstrates that while Latino lawyers have thrived financially and professionally, racism remains a powerful reality in their lives.

For example, Tony’s experiences with racism have seeped into every area of his life, not just in his profession and not just when he was young. When asked about the effects on his life of being a minority, he said, “I’m always aware of it. And it’s subtle. It’s subtle. … For example, when I bought my home [that] overlooks the water, I was outside and I don’t know what I was doing. My neighbor says: ‘Oh, are you the gardener?’ And my actual gardener, who is about 6’3” and a white guy with blonde hair, says, ‘No, that’s the owner.’ And the face on the person was, like, totally changed. And that’s what I have experienced for 55 years.”

In the survey, I asked Latino lawyers whether their ethnicity has caused them difficulties in their profession. The survey featured a two-part question. It had a yes or no box to be checked and then two lines to add a comment. Although 46 percent of the respondents answered yes, a significant number of those who answered no included comments that echoed the experiences of those who perceived race-based professional problems.

Photo by Corbis Images

Many of the comments included strong statements reflecting negative experiences with stereotypes and discrimination. The following examples are representative of their written comments:

• “Societal stereotypes are very common in the legal profession. Most people believe you are a clerk/bailiff or interpreter.”

• “Having to overcome other people’s prejudice; feeling different due to different values.”

• “Only to the extent that persons of color must be better than others to succeed. I truly believe this.”

• “Difficult to do jury trials because majority of jurors are retired white people.”

• “Not treated the same as my counterparts by courts, colleagues.” “Do not fit in with the big-firm culture.”

• “Only initially with other lawyers. Anglo clients rarely contact me, but Latino clients constantly do.”

• “Latinos are not well-regarded in this country and other professionals do not know how to interact (threatening?).”

• “I was not considered a good ‘mix’ for certain firms; looked upon as unqualified or undesirable.”

• “The primary difficulty being Latino/Hispanic has caused [me] has been in the interview process as I was seeking my first job. Later, it has been a problem working within the system due to systemic and long-held racial discrimination issues. I served on the original Minority and Justice Task Force and that confirmed my view about widespread discriminatory practice.”

• “People don’t take you seriously.”

• “Presumption of incompetence.”

• “Negative stereotypes: lazy, affirmative action.”

FOCUSING ON CHOICES

Many of these themes were elaborated on in the focus group interviews I conducted for the book. As one Latino lawyer stated:

“I think that I’ve given it my best good effort trying to deal with all these white groups, and I gave up! I have tried to go here and do that and do this. It’s just uncomfortable and I don’t like it. … I have business things I gotta do, and I can eat cheese and crackers like anybody else, a little wine. But I miss that Budweiser with carnitas. And I just want to go in, do my thing and get the hell out of there. … I’m tired of that bullshit game where I have to be a white guy.”

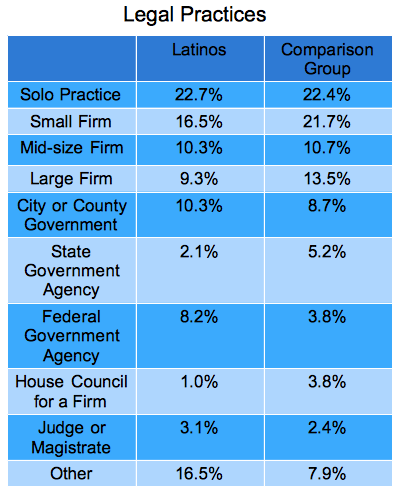

His statement demonstrates that the Latino respondents in this study attempt to resist prejudice by the manner in which they engage and participate in the legal profession. This includes the choices they make in the professional functions they attend, the type of law they practice and where they work. The majority of respondents believed a law degree would give them the tools to change the status quo or, one could argue, improve discriminatory conditions for Latinos that they themselves had witnessed and experienced.

As Anna’s and Tony’s experiences demonstrate, nearly all have experienced racism. Most of the Latino lawyers surveyed believe it is a common experience for almost all Latinos, and the Latino lawyers in this study have strong identities centered on and around the racialized experiences they’ve had in the United States.

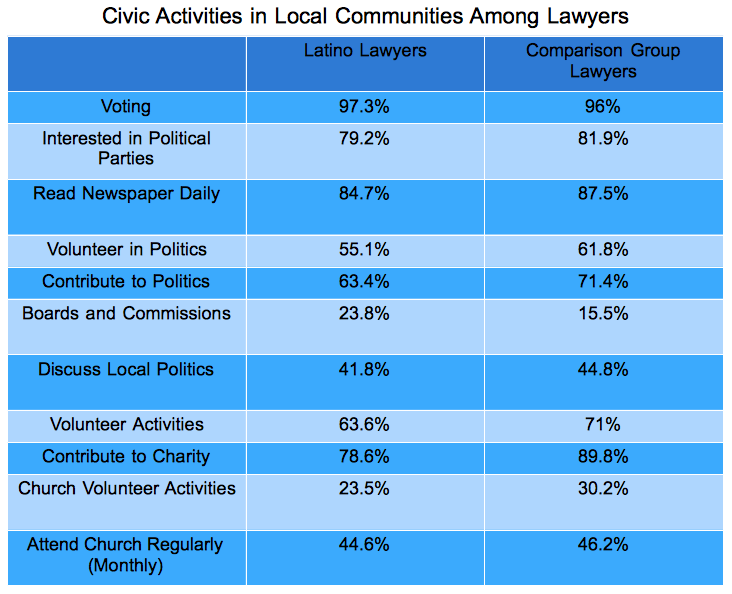

Their civic involvement is largely intertwined with the complexity of their sense of Latino ethnic identity and history—and the fact that they have had and continue to have unique struggles in their professional experiences. At the same time, they have transcended many of the obstacles that other Hispanics still contend with. They understand that their professional status is what separates them from the lives of less-privileged Latinos, and because of this many are committed to using their newfound professional status to not only give back to the greater Latino community but also improve prospects for social equity in the greater community.

But perhaps the most durable theme that emerged from the survey was the notion—often cited by other minorities—that Latino lawyers needed to be “10 times better” as professionals than their non-Latino counterparts. This subtle, pervasive sense—that throughout the day, every day they are being held to a higher standard by their colleagues, clients and even community members—is difficult to grasp in a personal sense, unless one has experienced it.

UNDERSTANDING THE EXPERIENCE

The demoralizing nature of dealing with the daily “micro-aggressions,” or of having one’s clients question one’s credibility and “proper credentials,” or the energy required in the fact that “you have to be 10 times better” or “most people believe you are a clerk/bailiff or interpreter,” cannot be emphasized enough. It can affect all aspects of one’s professional and civic life as an ethnic and racial minority professional in American society.

The fact that the Latino lawyers in this study are doing very well—at least as measured by their professional status, income, and professional satisfaction and engagement—paradoxically demonstrates the depth of our racialization: Even the most successful members of the Latino community, those who have “done everything right,” regularly experience some form of prejudice. These experiences, coupled with the low rates of people of color making partner, demonstrate racial and ethnic inequality in our legal institutions.

Understanding the experiences of Latino lawyers reveals a lot about inclusiveness in America, and about the consequences of a lack of diversity in the legal profession. The Latino lawyers in this study have roots in many different countries of origin and were raised in different areas of the U.S.; some are citizens and some are immigrants, yet the common denominator in all these stories is their experiences of marginalization and discrimination, and how that shaped their decision to become successful lawyers.

These Latino lawyers truly “come from a different world” than their colleagues—from their motivation in attending law school onward. And these Latino lawyers also have different experiences as lawyers than their white counterparts have.

All lawyers have challenging, demanding and sometimes overwhelming work, but for Latino lawyers there are often additional barriers to overcome in their communities and in their professions based on the need for greater acceptance and respect for differences.

Sidebar

Hispanic or Latino?

It’s not uncommon for non-Hispanics to be confused. But there’s no universal agreement, even within the Hispanic community, about which is the proper choice.

Culturally speaking, Hispanic is the more broadly used term in journalism and literature, since it was adopted by the Office of Management and Budget for use in the 1970 census to describe individuals of Spanish cultural heritage.

A 2006 survey by the Pew Hispanic Center found that 48 percent of Latino adults describe themselves first by their country of origin; 26 percent generally use the terms Latino or Hispanic first; and 24 percent generally call themselves American on first reference.

As for a preference between Hispanic and Latino, a 2008 Pew survey found that 36 percent of respondents prefer the term Hispanic, 21 percent prefer Latino, and the rest have no preference.

Maria Chávez, Ph.D., is an associate professor and chair in the department of political science at Pacific Lutheran University specializing in American government, public policy, and race and politics. Her book, Everyday Injustice, is published by Rowman & Littlefield.