The End of War and Slavery Yields a New Racial Order

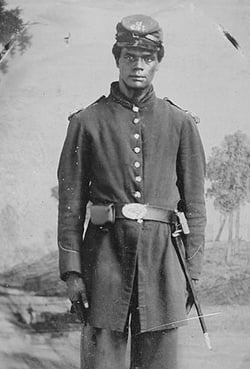

An unidentified soldier from Company B, 103rd Regiment (1863-65) With a forage cap designating the U.S. Colored Troops or U.S. Volunteers Service.

As the United States lurched into civil war during the winter and spring of 1860-61, the primary cause of the crisis was clearly on the minds of political leaders.

While many today think of the Civil War as a dispute over states’ rights, most Americans at the time understood that slavery was the central issue of the conflict. The slave states declared in their secession statements that they were leaving the Union to preserve human bondage—what Alexander Stephens, the vice president of the putative Southern nation, called “the cornerstone” of the Confederacy.

Four years later, Abraham Lincoln noted in his second inaugural address that on the eve of the Civil War, “one-eighth of the whole population were colored slaves, not distributed generally over the Union, but localized in the Southern part of it. These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was somehow the cause of the war.

“Neither party expected for the war the magnitude or the duration which it has already attained. Neither anticipated that the cause of the conflict might cease with or even before the conflict itself should cease. Each looked for an easier triumph and a result less fundamental and astounding.”

The most “fundamental and astounding” outcome of the war was the destruction of slavery. Congress, the military, state legislatures and the slaves themselves had taken part in the process. Lincoln essentially created the idea of an executive order to issue the emancipation proclamation. In 1865 the 13th Amendment made slavery illegal.

But other astounding things had happened. At the beginning of the war, federal law mandated a “white man’s army.” However, by the end of the war more than 200,000 blacks, many of whom had recently been slaves, served in the Army and Navy.

Shortly before Lincoln’s second inauguration, the black troops of the famous 54th Massachusetts Regiment—the “Glory Brigade”—had marched into Charleston, S.C. They sang “John Brown’s Body” as they entered the birthplace of secession.

Read all the articles in our special report:

- An Inescapable Conflict

- Lincoln and Davis: A Friendship That Made History

- Secession: How the South Nearly Won

- Lincoln’s War Powers: Part Constitution, Part Trust

- The Dawn of a Republican Court: Lincoln’s Justices

- The End of War and Slavery Yields a New Racial Order

- The Conspirators: Tried by Military Commission

- Gallery: Civil War-Era Legal Figures

A few weeks later the all-black Massachusetts Fifth Cavalry led the United States Army into Richmond. Uniformed black men, on horses, carrying repeating rifles in the capital of the Confederacy: The changes were indeed astounding.

Beyond the military, the changes were both substantive and symbolic. In 1862 Congress ended slavery in the nation’s capital through compensated emancipation, using the Fifth Amendment’s takings clause to end the denial of liberty without due process to the thousands of slaves in Washington. When issuing new charters for street railroads in the capital, Congress required integration and equality on the cars. Disregarding Chief Justice Roger B. Taney’s opinion in Dred Scott, Congress freed all slaves in the federal territories while the State Department issued passports to blacks. Black citizenship was becoming a reality. Equally symbolic was the American president publicly having tea with the black abolitionist Frederick Douglass, and then warmly walking with him arm-in-arm at an inaugural party.

As the war ended, the reality of a new racial order was apparent. Full racial equality was not yet on the horizon, but slavery was over and blacks were already gaining rights.

Sadly, many of those gains would be undermined or destroyed by Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, and later by the counterrevolution of Southern whites after Reconstruction. But even as blacks were segregated and disenfranchised from the 1880s onward, the profound changes that came with the destruction of slavery remained embedded in the Constitution and our nation’s historical memory, to be resurrected nearly a century after the Civil War ended.

Paul Finkelman is the President William McKinley Professor of Law and Public Policy at the Albany Law School.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.