The Age of Innocents

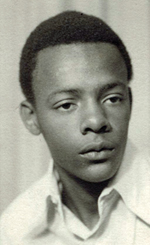

Barney Brown

Photo courtesy of Barney Brown

Barney Brown should have listened to his mother that fateful day in 1970 when she told him to stay home while she was at work.

But Brown, then 13 and living in Hollywood, Fla., did what many teens do: He ignored his mother and snuck out with friends.

“I thought I’d be back before she got home,” he says. But Brown didn’t come home for 38 years.

While out with his friends that day, police stopped the car in which he was a passenger. Brown, an African-American, was arrested for raping a white woman and robbing her husband.

Police then held the teen without charges for four days, during which time, Brown claims, they brutally beat and interrogated him while trying to force a confession. His parents weren’t notified that their son was in police custody, even though they had called police to report him missing.

Despite Brown’s repeated protestations of innocence—and numerous lineups in which the victims failed to identify him—prosecutors tried him as a juvenile for rape and robbery. After an acquittal, prosecutors used a quirk in the law to retry Brown as an adult. He was convicted and sentenced to life in prison.

Brown was released from prison in September 2008 after lawyers persuaded a judge that the second prosecution violated the constitutional protection against double jeopardy.

Brown’s story is horrific, but it’s hardly unique. This past fall, Northwestern University School of Law launched the Center on Wrongful Convictions of Youth to help others like Brown.

The center, the first of its kind, is a joint project of the law school’s Center on Wrongful Convictions and its Children and Family Justice Center.

“We want to take a closer look at youth as a risk factor for wrongful convictions, particularly in the interrogation context, where a lot of these cases first go wrong,” says Northwestern law professor Steven Drizin, also the legal director of the Center on Wrongful Convictions.

Drizin says his work on behalf of wrongfully convicted adults helped him see the need for an organization devoted exclusively to some of the unique issues that contribute to the wrongful conviction of youths: adolescent brain development and competency, the increased risk of a false confession, the unreliability of young witnesses, and the limited ability of nonadults to understand the legal proceedings against them.

University of Michigan law professor Samuel Gross, who studies false convictions and exonerations, calls the center a terrific idea and hopes its work will help shed light on what is going on in juvenile courts. According to his research, juveniles sentenced as adults are overrepresented among those exonerated. Of the 340 reported exonerations between 1989 and 2003, almost 10 percent were juveniles at the time of their convictions.

Gross says false confessions also play a large role in the wrongful convictions of juveniles. Of the 32 cases he documented, 13—or 42 percent—involved false confessions.

“There’s no reason to think the juvenile courts are any more accurate than the adult courts are, and there is some reason to believe they may be even less accurate,” he says.

Much like Northwestern’s center for wrongfully convicted adults, the juvenile arm will litigate credible claims of innocence by convicted prisoners. It also will research the causes of wrongful convictions of youths and advocate for policy reform.

Web extra:

See excerpts from the Center’s symposium on wrongfully convicted youth.