The President v. Omarosa: Winning at arbitration, against the odds

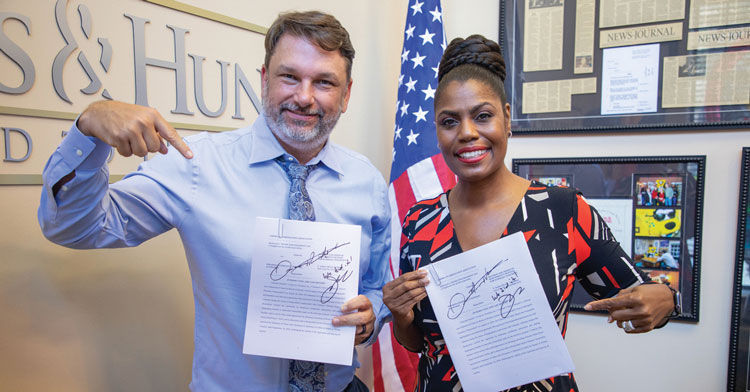

John M Phillips and Omarosa Manigault Newman. Photo by Law Offices of Phillips & Hunt.

It was fate that brought Omarosa Manigault Newman and me together back in 2013, when we were both guests on Jane Velez-Mitchell’s HLN television show. I was there with the family of Jordan Davis to talk about their son who had been killed in Jacksonville, Florida, in a confrontation arising from racism and a dispute over loud music.

Afterward, I followed Omarosa on social media and sent her Jordan Davis wristbands. I remember the excitement when she followed me back on Twitter. I told my wife, “Well, look at that!” I thought I had made it.

Meanwhile, 1,000 miles away, Donald Trump was planning his run for president of the United States. By the end of 2015, Omarosa, who had appeared on Trump’s show The Apprentice, reached out to his team to join the campaign.

It took a while for the campaign to get properly assembled, but on July 25, 2016, Omarosa asked Trump’s team: “Can you let me know when I will get my NDA and paperwork and an official date for my announcement?” This was a pivotal question, as Omarosa’s NDA, or nondisclosure agreement, would become the center of a legal battle pitting the president of the United States against his former employee, who became my client.

Stifling speech

An NDA is an agreement designed to keep secrets, and these sorts of clauses have come under increasing scrutiny by courts.

The NDA in Omarosa’s employment contract was facially overbroad, vague, even venturing on the comically obtuse. Yet people signed NDAs in droves to secure White House jobs.

In the end, Omarosa accepted a position as a senior adviser and did her job well—so well that she made enemies on all sides. But Omarosa was also prudent, keeping copious notes and recording conversations. Indeed, the onetime “apprentice” was an apprentice no longer.

In December 2017, Omarosa’s employment was terminated by Chief of Staff Gen. John Kelly in the White House Situation Room—a room usually reserved for extremely important or top-secret meetings. During the meeting, Omarosa recorded Kelly using what she considered veiled threats about her reputation in an attempt to intimidate her from speaking out in the future.

Shortly thereafter, I got a call from Omarosa. I had just landed in the Bahamas and was in a cab. I told her I would call her back when it was more private. Once in my hotel room, she unloaded the whole story on me.

Several months later, things began to escalate. Omarosa had gone on Celebrity Big Brother and said the president’s administration was “not my circus, not my monkeys.” She would eventually be sued for this very statement.

She also said, “I was haunted by tweets every single day, like what is he going to tweet next?”

And when asked by fellow celebrity cast member Ross Mathews, “Would you vote for [Mr. Trump] again?” Ms. Manigault Newman responded, “God no, never. In a million years, never.”

These were part of the allegations in a multimillion-dollar lawsuit filed against Omarosa for breach of her NDA.

Omarosa described the White House as a “den of distrust,” and she was willing to not only talk about it, but also to write about it. On Aug. 14, 2018, Omarosa published a book titled Unhinged: An Insider’s Account of the Trump White House, in which, among other things, she called Trump unqualified, narcissistic, misogynistic and racist. Omarosa asked me to go on the publicity tour with her as an adviser, and I accepted.

The litigation

After the release of Omarosa’s book, Trump filed an arbitration action, claiming she had violated her agreement not to disclose “confidential information.”

At its core, this was a seminal First Amendment issue with the questions of whether a president can prevent citizens from stating their opinions and whether government entities can protect immoral or illegal behavior in office through NDAs.

The case escalated quickly. Trump called Omarosa a “dog”on Twitter. Omarosa went on Meet the Press to promote her new book. Motions to dismiss, motions for summary judgment and countless pages of briefs were filed and counter-filed. All of a sudden, we were watching impeachment hearings not only as concerned American citizens but to counter a defamation suit.

In February 2020, we finally had a full-day arbitration hearing in New York City. At its conclusion, every count was dismissed. We celebrated on the marquee of the Hard Rock Café in Times Square.

But the celebration was short-lived. The arbitrator allowed the Trump campaign to amend its petition. The amended complaint included hundreds of new allegations. More weaponized litigation followed. We were granted discovery but lost a motion to depose Trump—the only person allowed to determine what was considered “confidential information” in his own NDA and who bragged about “suing Omarosa” on Twitter to intimidate others similarly situated.

I don’t think I’ve wanted to take a deposition more. We didn’t need it, but we wanted it.

Standing up to Goliath

Weaponized litigation kills justice. It wastes resources and allows the powerful to win by financially exhausting the other side.

We had nothing to lose and everything to win, yet the thousands of hours of essentially unpaid work was, at times, overwhelming.

This case should have been unimaginable—a United States president attacking fundamental constitutional rights through outrageously unenforceable nondisclosure agreements. It took far too long to get past the frivolous defenses and experts while lawyers like Charles Harder billed Trump’s campaign millions of dollars. All in an attempt to stifle free speech.

We won in the Trump campaign’s chosen forum. In April, we received a $1.3 million attorney fee award. You win big cases by accepting tough challenges. As lawyers, we have an obligation to confront injustice. We hope this energizes more lawyers to take on David vs. Goliath cases.

I hope more people will come forward and blow the whistle on corrupt government behavior. Kudos to Omarosa Manigault Newman for not backing down. It was a team effort and a win we can all be proud of.

John Phillips is the founder of Phillips & Hunt, based in Jacksonville, Florida, with offices in multiple states. The firm takes on a variety of cases, including personal injury, criminal justice and family law.

This column reflects the opinions of the author and not necessarily the views of the ABA Journal—or the American Bar Association.