The ABA has advocated for people with HIV/AIDS for more than 30 years

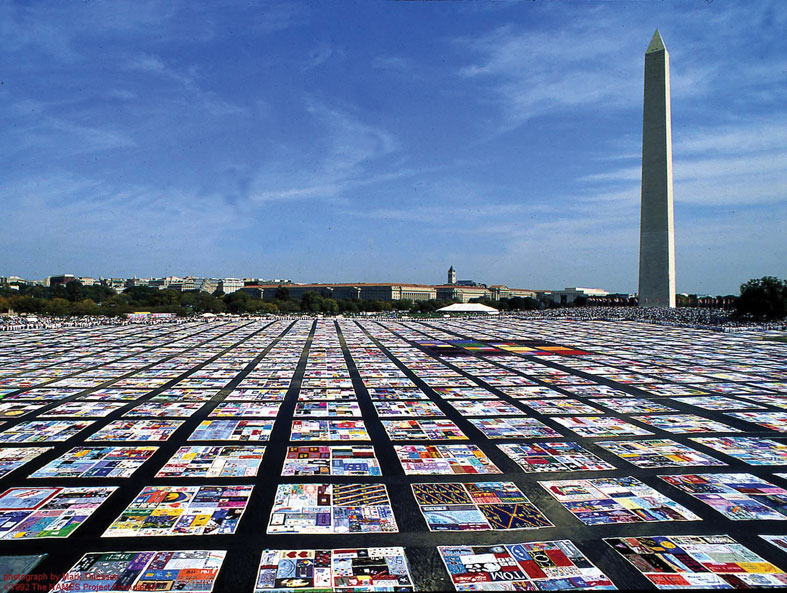

In 1996, when the entire AIDS Memorial Quilt was last displayed, it covered the National Mall. Today, over 105,000 people are memorialized on its panels. Photo courtesy of National Institutes of Health, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

While the American Bar Association has mobilized to help the public and profession during the COVID-19 pandemic, this is not the first time the association has addressed the challenge of a new and deadly virus.

At the height of the United States’ AIDS epidemic, the ABA helped lead the charge to decrease discrimination against people who were infected with HIV.

The ABA established the AIDS Coordinating Committee in 1987. In its first year, the group held a series of hearings with lawyers, health care providers and people living with HIV/AIDS around the country.

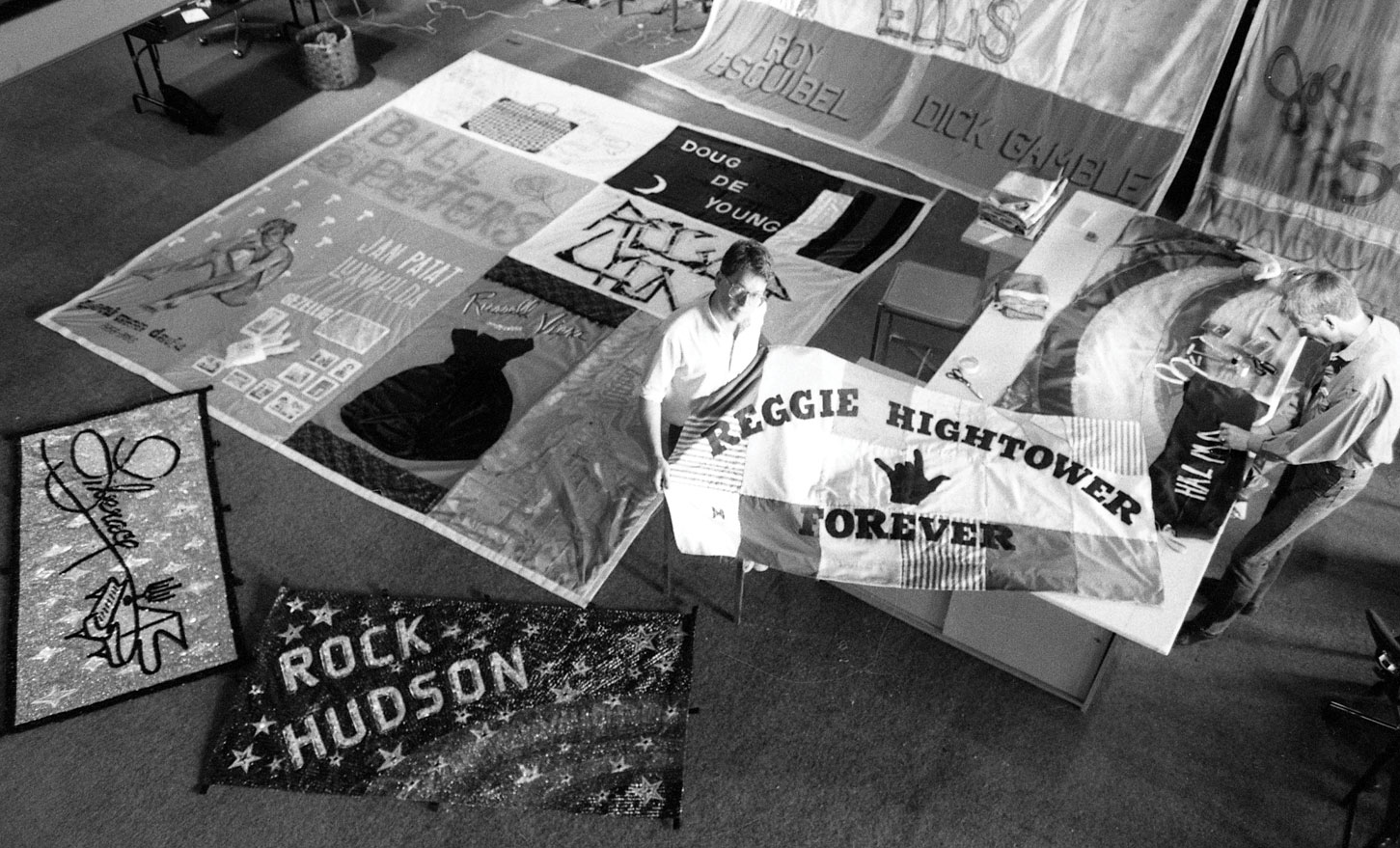

San Francisco-based LGBT activist Cleve Jones (center) helped found the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt in 1987. He created the first panel to honor his friend Marvin Feldman. Photo by Liz Hafalia/The San Francisco Chronicle via Getty Images.

Barry Sullivan was the first chair of the committee, and he hoped the hearings could inform the ABA’s response to the epidemic. He remembers being moved by people who were affected by the virus. In some cases, he heard testimony from people living with HIV who died months later. “On one hand, we were the first entity that really tried to put the response to HIV on a firm scientific basis,” says Sullivan, a professor at Loyola University Chicago School of Law. “At the same time, we were also at the forefront of trying to understand these problems from a humane point of view.”

According to World Health Organization statistics, approximately 76 million people globally have been infected with HIV and about 33 million of them have died of since the beginning of the epidemic.

The AIDS Coordinating Committee, now known as the HIV/AIDS Impact Project, has continued to shape the conversation around the crisis. It develops legal and policy recommendations; drafts informational materials for judges and lawyers; and hosts educational events and webinars.

It also organizes a biennial conference for HIV law practitioners, policymakers and advocates, and it recognizes lawyers and legal service providers with its Alexander D. Forger Awards for Sustained Excellence in HIV Legal Services and Advocacy.

Patricia Davidson worked with Sullivan as the committee’s first project coordinator. The former congressional liaison for the AIDS Action Council says the ABA “legitimized the issue.”

Organizations such as ACT UP were powerful advocates for those with HIV/AIDS. Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

“The people on our committee, even though they represented many different areas of the law and some were fairly conservative, were highly committed,” says Davidson, now a freelance teacher. “People stepped up. They saw there was a real problem and there was absolutely nothing to be gained in stonewalling or staying in our silos.”

The early years

The AIDS Coordinating Committee was the brainchild of then-ABA President Robert MacCrate and Bill Robinson, then the executive director of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law and chair of what is now the Section of Civil Rights and Social Justice.

In addition to its hearings, the committee drafted AIDS: The Legal Issues, a 250-page report that was one of the first resources to analyze legal controversies arising out of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. The committee’s findings were presented at the 1988 ABA Annual Meeting.

AIDS patients such as Priscilla Diaz faced separation from their children when they were too ill to care for them. In this 1986 photo, the 36-year-old visits with her children Jasmin, Saul and Christian. Her husband had already passed away from AIDS. Photos by Jim Hughes/NY Daily News via Getty Images.

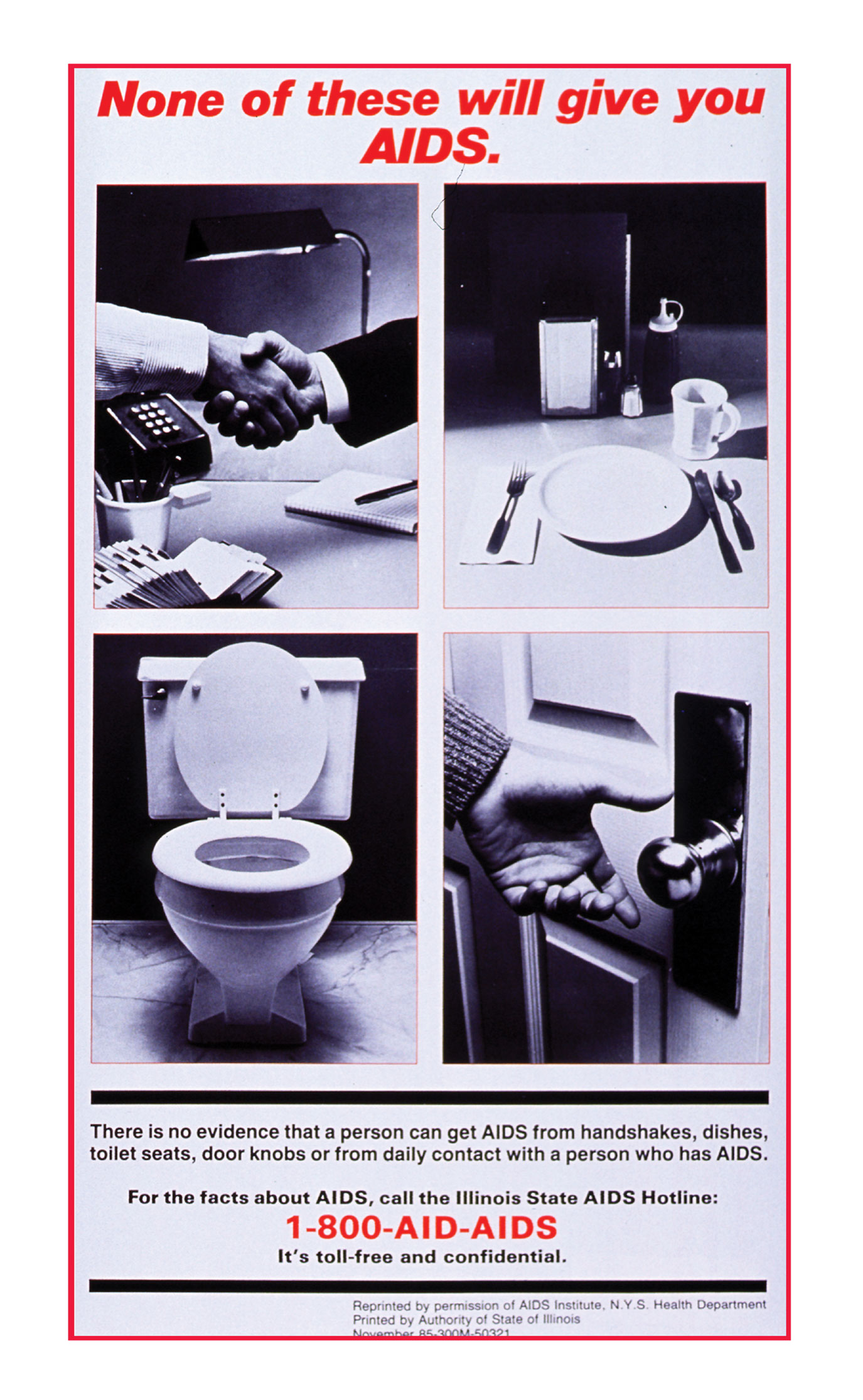

“It was everything from what immigration policies should be to how prisoners affected by HIV/AIDS should be handled,” Sullivan says. “At that point, one of the really horrendous things that people don’t remember anymore is that judges were requiring bailiffs to wear hazmat suits if they came in contact with a defendant in a criminal case who was HIV-positive.”

A year later, the AIDS Coordinating Committee introduced an omnibus resolution urging federal, state, local and private entities’ policies to be consistent with 62 principles in 15 legal areas, such as confidentiality, employment and discrimination. The House of Delegates adopted them all.

Davidson says the ABA’s leadership was important because at that point, there were no federal laws related to HIV/AIDS. In 1990, Congress passed the Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency Act, which created the largest federal program to focus on providing care and treatment to people with HIV.

Congress also passed the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990, which Davidson describes as an “important evolutionary step” in recognizing that people with HIV/AIDS needed protection against discrimination.

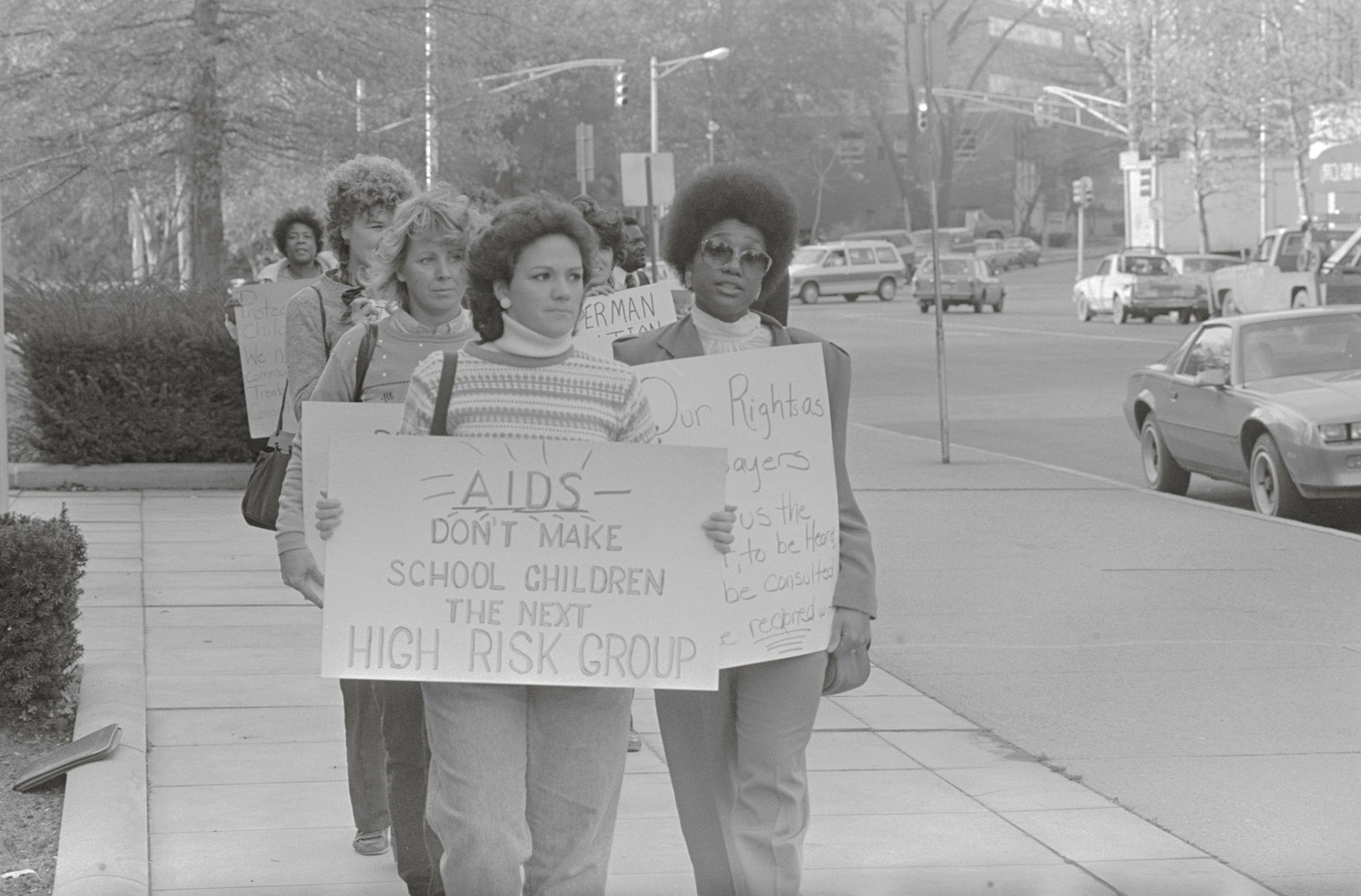

Ignorance and fear of infection drove stigma against people with HIV, leading to the isolation of even children with the virus. Photo by Bettmann/Contributor.

“It was one of the primary tools for people with AIDS and HIV or even gay men, who were relying on it because they were being discriminated against based on the often-erroneous perception that they might be asymptomatic carriers,” she says.

‘An educating body’

Over the years, the AIDS Coordinating Committee focused on specific issues, including criminal justice and public health.

Richard Andrias understood the intersection between HIV/AIDS and criminal justice even before he joined the committee.

Ignorance and fear of infection drove stigma against people with HIV, leading to the isolation of even children with the virus. Photo by Bettmann/Contributor.

A former criminal court judge who became a justice on the New York State Supreme Court in 1988, he helped the Association of the Bar of the City of New York produce a report detailing how defendants with HIV/AIDS were deprived of their legal rights and provided inferior health care.

Around the same time, the AIDS Coordinating Committee produced its own recommendations for responding to HIV/AIDS in the criminal justice system. After the House of Delegates adopted them in February 1989, they became the ABA’s basis for educating judges, lawyers and courthouse staff.

“Using the ABA as an educating body is helpful if you want safety for defendants and to not have their rights denied just because they have a disease,” says Andrias, who served as chair from 2003-2006 and retired from the bench in 2018. “It’s also helpful for court systems and lawyers so they don’t make ridiculous decisions that aren’t science-based or based on rights.”

Robert Stein worked on HIV/AIDS issues with the Union of American Hebrew Congregations before he became committee chair in 1997.

Stein learned about needle-exchange programs—which reportedly cut HIV transmission and helped encourage drug users to seek treatment—and worked on a proposal supporting them. Since it wasn’t an issue that all ABA members understood, the committee worked out a compromise.

“What we tried to do was make it clear that HIV was a bloodborne disease and needles were shared,” says Stein, who is now retired and lives in Washington, D.C. “As a public health measure, you really wanted to get people off drugs, but you also wanted to make sure they did not contract a deadly virus.”

Needle exchanges coupled with drug-treatment referral programs have been championed by the ABA to help mitigate the danger of disease transmission since 1997. Photo by Michael Robinson Chavez/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images.

In August 1997, the House of Delegates adopted the resolution, which stated the ABA’s opposition to substance abuse and supported needle-exchange programs that included drug counseling and treatment referrals.

“Needle exchange became a very important part of HIV management,” Stein says.

Looking ahead

In the last few years, the AIDS Coordinating Committee has revised its earlier policies on HIV/AIDS to enhance them with modern language and insights.

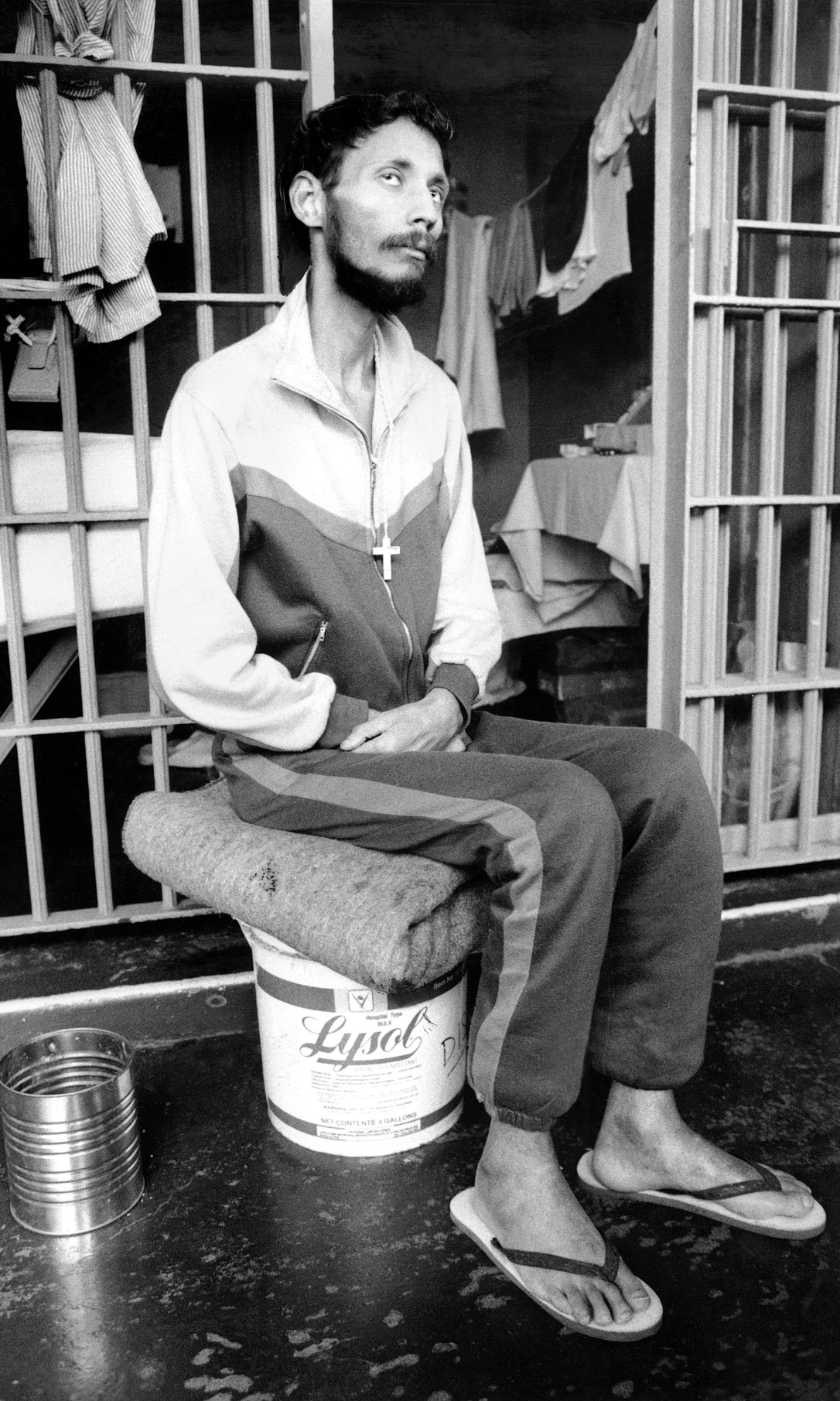

The ABA worked to protect the rights of prisoners with HIV/AIDS such as Jose Ramos, shown here in 1987 at Rikers Island Hospital in New York. Photo by Monica Almeida/NY Daily News via Getty Images.

Then-chair Richard Wilson worked on the updated omnibus resolution that the House of Delegates approved in February 2018. He also decided to reexamine the direction of the committee because of the shift in public perception of HIV/AIDS.

“We spent a lot of time trying to reassess what we might be doing, because A) everything is fluid, and B) it hasn’t gone away,” says Wilson, who practices family law in Chicago. “There is a profound lack of consciousness about it, certainly within the gay community compared to 15 years ago, and it isn’t much better in the broader community.”

In 2018, the committee became the HIV/AIDS Impact Project, a part of the Health & Human Rights Initiative run by the Center for Human Rights and Section of Civil Rights and Social Justice. Although Wilson says COVID-19 derailed a lot of its work, the project did help improve the availability of HIV legal services.

In December, the HIV/AIDS Impact Project announced grants of up to $150,000 each to nine HIV legal services providers from its HIV Legal Services Fund. The ABA received $1.2 million in cy pres funds from the settlement agreement in Beckett v. Aetna. In this class action lawsuit, policyholders taking HIV medications alleged privacy infringement in 2017 by the Aetna insurance company.

The HIV/AIDS Impact Project also supported a resolution co-sponsored by the Section of Civil Rights and Social Justice and Commission on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity urging the U.S. Department of Defense to declare that HIV status alone shouldn’t disqualify someone from military service. The House of Delegates approved it in February.

Margaret Drew, the project’s current chair and an associate professor at the University of Massachusetts School of Law, hopes to focus on more issues as the COVID-19 pandemic winds down.

This includes the criminalization of people with HIV, she says, since many states require the disclosure of HIV status to a sexual partner. It also includes discrimination, which still occurs in the workplace and other settings.

Drew adds that older people with HIV have said they were reminded of the stigma they’d faced when they saw similar responses from the public to people with COVID-19.

“This work is critical because those living with HIV or AIDS are a marginalized population,” Drew says. “Regardless of income and status, all people with HIV are at risk in ways that others are not. It is significant that early in the AIDS epidemic, the ABA was willing to take on this project and has supported the continued needs of those living with HIV.”

This story was originally published in the August/September 2021 issue of the ABA Journal under the headline: “Long-term Caring: The ABA has advocated for people with HIV/AIDS for more than 30 years.”