Talk of reparations is being revived around the country

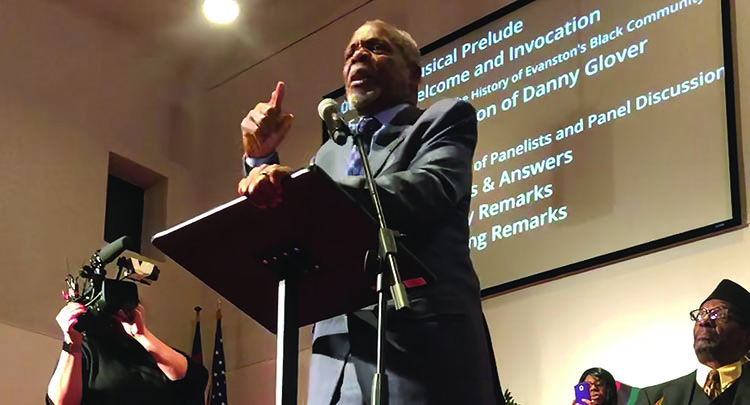

Actor Danny Glover was the keynote speaker at the December town hall in Evanston, Illinois. Photo by Liane Jackson/ABA Journal

Photo of Liane Jackson by Callie Lipkin/ABA Journal

Intersection is a column that explores issues of race, gender and law across America’s criminal and social justice landscape.

Reparations is having a moment—400 years after the U.S. slave trade began, 157 years following the Emancipation Proclamation and 56 years post-Jim Crow. Although state-sanctioned discrimination is over, those who support reparations say the compounding damage remains from past atrocities never redressed.

These days, whispering “reparations” is no longer taboo. Some Democratic presidential candidates openly announced support of reparations for black descendants of slaves; most others agreed the issue should be studied. Cynics consider the tepid national dialogue as pandering to the black base or an esoteric exercise untethered to action—but the fact that reparations is being talked about at all shows, ultimately, that an accounting for the dark legacy of our nation’s original sin cannot easily be swept under the rug.

So here we are in this moment, propelled in large measure by journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates’ 2014 devastating deep-dive article “The Case for Reparations” and anchored by decades of quiet persistence by activists to at least be heard.

40 acres and a mule

The idea of reparations is nothing new. It began during Reconstruction, when Gen. William T. Sherman’s “40 acres and a mule” promise to an estimated 4 million emancipated slaves never materialized. Instead, freedmen were often plunged into indentured servitude, sharecropping or other forms of forced labor. Black Americans were subjected to a de facto terrorist state, with regular lynchings, Jim Crow, land and property theft, mass incarceration, educational and health inequality, redlining, labor market discrimination and systemic police brutality.

For almost three decades with no success beginning in 1989, the late U.S. Rep. John Conyers introduced H.R. 40, a bill intended to establish a commission to study the legacies of chattel slavery and investigate reparations proposals. Texas Democrat Sheila Jackson Lee reintroduced H.R. 40 in 2019, and Cory Booker co-sponsored the bill in the Senate.

But while Congress takes baby steps toward considering whether it will vote to even consider the idea of reparations, some local governments are taking matters into their own hands.

‘The Rosa Parks of reparations’

Reparations is a movement in need of a hero, and Alderman Robin Rue Simmons’ success story in Evanston, Illinois, has become a beacon for civil rights advocates eager to demonstrate the feasibility of reparative justice in practice. In 2019, Simmons spearheaded an effort to earmark money from taxes on recreational marijuana sales to pay reparations to the city’s black residents. During a December town hall meeting on the issue at Evanston’s First Church of God, one national activist called Simmons “the Rosa Parks of reparations.”

Taxing marijuana proceeds is a radical and symbiotic solution to the problem of how reparations would be funded, and activists hope it can become a model replicated in other cities. Simmons argued African Americans should disproportionately benefit from the sale of marijuana in the same way they were disproportionately damaged by the policing of the drug though racially biased arrests. Data compiled over a three-year period in the Chicago suburb showed that more than 70% of those arrested on marijuana charges were black.

In Evanston, as in many American cities, glaring disparities exist: According to reports by the city council, residents of color have been systematically subjected to redlining and predatory lending, and they are being priced out of their homes.

The 3% tax on recreational marijuana is expected to generate between $500,000 and $750,000 in revenue each year, which would be earmarked for the city’s reparatory justice projects, with a cap of $10 million over the next 10 years. Although the city council passed the measure in November, details on how the reparations will be disbursed are ongoing.

Simmons has said measurements of success can include increased black household income, increase in revenue for black-owned businesses and improved infrastructure for historically black and redlined neighborhoods.

Generational work

In America, where help for marginalized populations is often denigrated as a handout, critics wonder why descendants of slaves are entitled to reparations at all. The U.S. clings to a deeply held notion of a “colorblind” society where if you just work hard enough, you can succeed and transcend—and if you don’t, you have only yourself to blame. But reparations architects point to a long and cumulative history of discrimination and violence that transcends slavery. Put into perspective, a 2016 report by the Institute for Policy Studies and the Corporation for Enterprise Development found it would take the average black family 228 years to build the wealth an average white family holds at this moment.

The case for reparations has understandably sown deep divisions, even in Evanston, and faces an uphill battle nationwide. Actor and humanitarian Danny Glover, who was the keynote speaker at the city’s December town hall, called the push for reparations “generational work.”

“They have stood in the fire to make this happen,” Glover said, describing the agitation of past civil rights pioneers and present-day activists.

“This is a remarkable step,” Glover continued. “Right now, some action is taking place right here. And the world has come to see that, and they will know it’s possible.”

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.