On the morning of Jan. 12, 1999, Verna Williams needed some extra motivation. She was about to argue in Davis v. Monroe County Board of Education before the U.S. Supreme Court and wanted to look as “badass” as possible. So she decided to dress all in black, wearing a mock turtleneck and a suit.

That badass attitude was nothing but a distant memory by the time she took her seat at the table with co-counsel Marcia Greenberger. She felt anything but confident, and even though she was set to argue first, there was still plenty of time for the butterflies to flutter and the dread to marinate. This was Williams’ first time in front of the nine justices and only her third oral argument.

As vice president of the National Women’s Law Center, she was lead counsel in a case asking the court to hold schools liable for student-on-student sexual harassment. The petitioner, a mother suing on behalf of her fifth-grade daughter, had lost in both district and appellate court.

As Williams glanced around the courtroom and saw her friends and family, it felt like everyone she knew was there to watch her either nail the argument or flame out spectacularly.

"On the inside, I'm sweating bullets." -Verna Williams

Then all of a sudden, a gavel echoed around the chamber, the justices appeared from behind heavy burgundy drapes to take their seats, and the marshal cried, “Oyez!” Before she knew it, she was up at the podium standing before the nine.

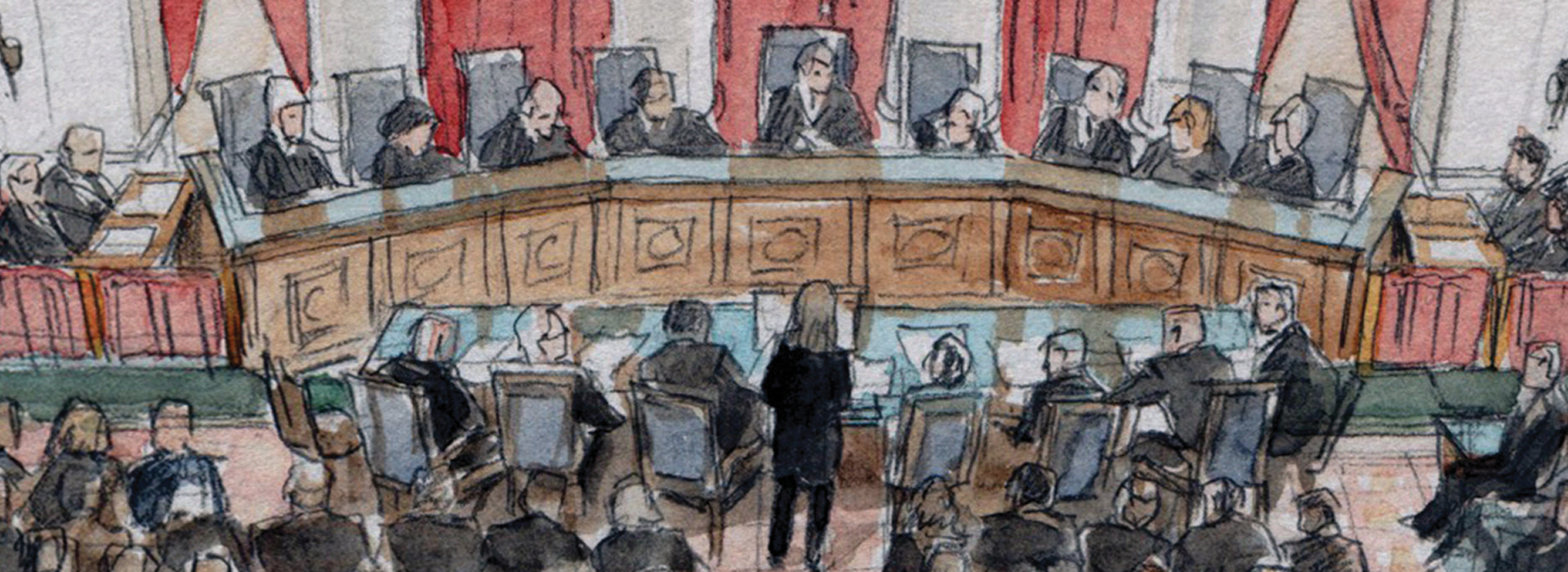

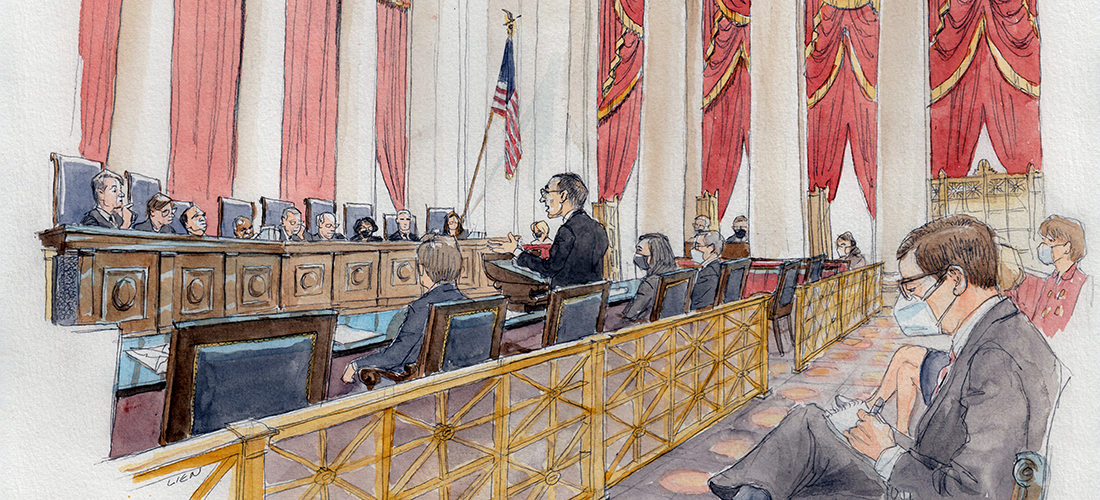

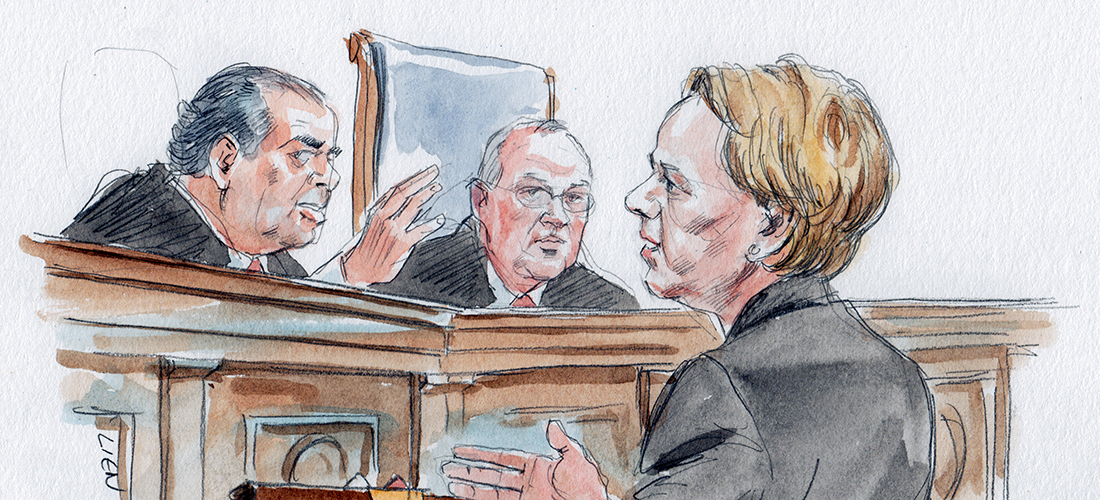

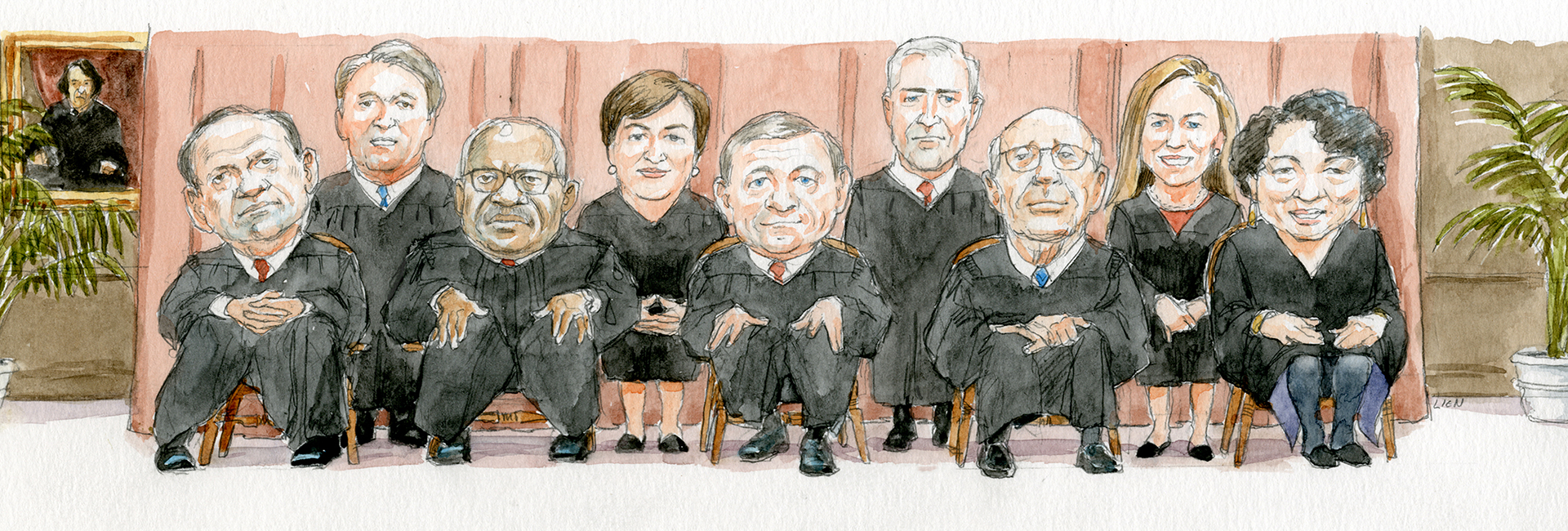

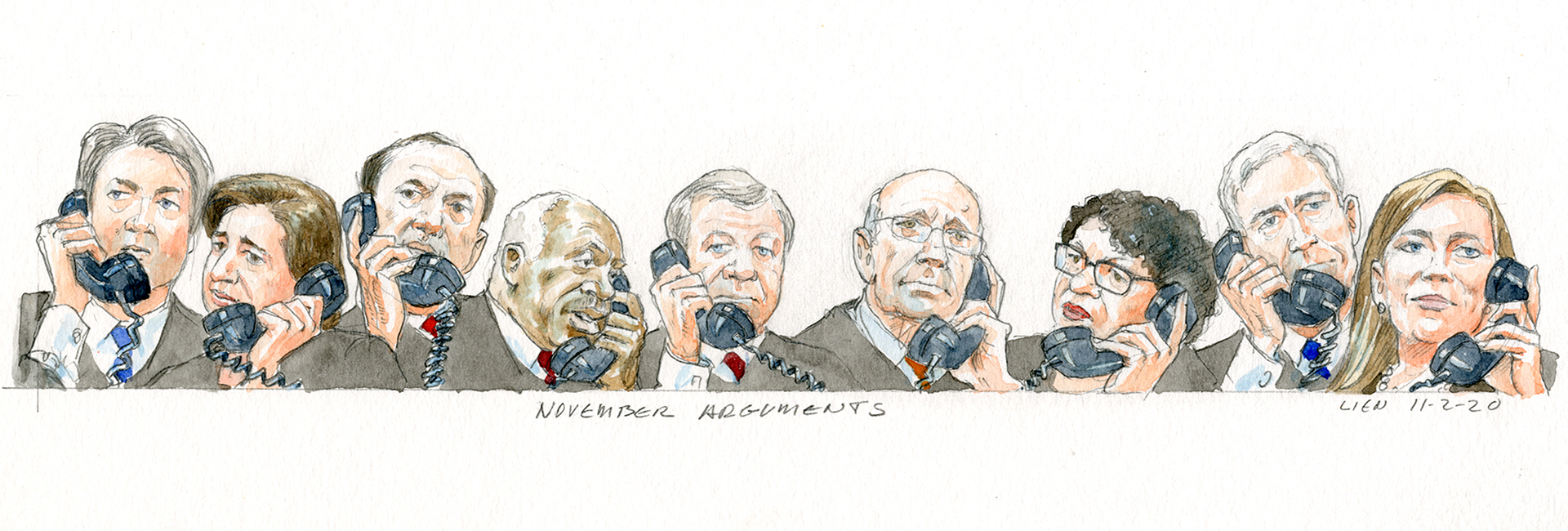

Photo gallery: The Courtroom Art of Art Lien.

“I was really, really nervous. My heart was pounding, and I had a sick feeling in my stomach,” says Williams, whose side prevailed on a 5-4 vote. “On the inside, I’m sweating bullets.”

For Williams and other first-time advocates, it can also come as a shock when they realize how close they are to the justices—so close some are just out of their sight line. In the words of Supreme Court veteran Neal Katyal, Chief Justice John Roberts “sees everything—he sees you sweat.”

The intimate setting also leaves advocates feeling both boxed in and exposed. Small gestures are amplified, and routine moves are second-guessed. Douglas Hallward-Driemeier, who would go on to argue the landmark 2015 case Obergefell v. Hodges enshrining the right of marriage for same-sex couples, says his mouth was dry during his first time before the justices. But he dared not reach for a glass of water.

“I thought, ‘If I pick up that glass of water, I’m going to spill it all.’ I just grabbed back onto the podium and held on for dear life until it was over.”

For some advocates who have walked up the 44 steps to the Supreme Court building designed by architect Cass Gilbert and through the main entrance etched with the words, “Equal Justice Under Law,” that first argument felt like a dream come true.

“I’ve just been so fortunate to be able to do something like this,” says Christopher G. Browning Jr., who as a high schooler dreamed of one day appearing at the court and won 7-2 on his first go-around in the 2010 False Claims Act case Graham County Soil and Water Conservation District v. United States. (Hallward-Driemeier also made his first argument in that case as amicus curiae on behalf of the United States.) “Once you argue your first Supreme Court case, you’re addicted and want to go back. There’s nothing that compares in the practice of law.”

All the same, many feel the weight of history and knowledge that their arguments result in decisions impacting all facets of American life.

"Once you argue your first Supreme Court case, you're addicted and want to go back. There's nothing that compares in the practice of law." - Christopher G. Browning Jr.

The experience can be overwhelming. Speaking at the Clio Cloud Conference in Nashville, Tennessee, in October 2022, Katyal recalled that before his first argument, he attended several Supreme Court hearings. Rather than settling his nerves, it made him more anxious. So much so, clerk William K. Suter put an arm around him one day and said not to worry. After all, he told Katyal, “only three people have died with their boots on.”

“What?” Katyal replied.

“Yeah. Only three people have died at the podium arguing Supreme Court cases,” Suter joked, according to Katyal.

“Not exactly what you want to hear before you’re arguing your first case before the Supreme Court,” he said.

Jean-Claude André, now a partner at the law firm Bryan Cave, was 31 when, in October 2006, he argued before the Supreme Court for the first time. He won a unanimous ruling in the consolidated cases Jones v. Bock and Williams v. Overton after urging the court to find that prisoners bringing civil rights lawsuits do not have to show they already have exhausted all administrative remedies.

He says advocates should take some comfort in knowing at least some justices are probably on their side.

“Usually, you’ve got at least one friend up there,” André says.

But first, advocates have to persuade the court to take on their cases. Each term, 5,000 to 7,000 cases are filed at the court. The high court, on average, hears oral argument in only about 80 cases. In the 2021-2022 term, the court reversed lower court decisions in 82% of cases.

Win or lose, many attorneys prepare for their half-hour argument like their lives depend on it. For most advocates, that means testing their case in round after round of moot courts in which other lawyers and legal practitioners stand in for the justices.

"I remember thinking, 'None of my argument makes sense.'" -Jessica Ring Amunson

Law firms typically put their attorneys through the paces in several of these practice sessions so when they appear in court, there aren’t many questions they haven’t considered.

However, not every attorney is on sure footing afterward. Jessica Ring Amunson, a partner at Jenner and Block, was rattled after her final session with seasoned Supreme Court lawyer and former U.S. Solicitor General Donald B. Verrilli Jr.

“I remember thinking, ‘None of my argument makes sense.’ Having a day to put myself back together again and reformulate things was helpful. But I came away from that last one feeling: ‘This is going to go very badly,’” says Amunson, who argued a guilty plea does not necessarily prevent a defendant from appealing the constitutionality of their conviction in the 2018 case Class v. United States. The court ruled 6-3 in her client’s favor.

The moot courts Katyal did also shook his confidence, his co-counsel Charles Swift recalls. He was representing Osama bin Laden’s driver and bodyguard, Salim Ahmed Hamdan, in the 2006 case Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, which challenged the military commissions trying detainees at Guantanamo Bay. Katyal, a Georgetown Law professor then in his mid-30s, was set to face off against U.S. Solicitor General Paul Clement, a Supreme Court veteran who already had argued dozens of cases.

Swift says he suggested a more unorthodox approach after Katyal’s arguments failed to resonate. (Katyal was unavailable for an interview.) “I wasn’t doing better. I got some good lines for the briefs and came up with the one-liners and stuff like that. But I wasn’t getting it done, and I was scared. And so I brought Josh [Karton] in,” Swift says.

Karton “specializes in applying theater and film communication techniques to the art of trial advocacy,” according to his online biography. Swift and Katyal call him an acting coach, although Karton prefers the term trial consultant.

Katyal was skeptical. According to Swift, he said: “This is the biggest waste of time. I can’t believe I’m doing it.”

"The words are the least of it in one way. Words are a delivery system for something greater." -Josh Karton

Matters weren’t helped when the bearded Karton arrived at his office at Georgetown for their first appointment wearing a billowy white shirt and Joseph Abboud bow tie, his hair tied back into a ponytail. He “obviously looks like some guy from acting school,” Swift says.

When Karton saw Katyal with his arms folded, he sensed his unease but asked the law professor to humor him. Over the course of several sessions, he had Katyal recite his argument, which he duly read off a legal pad.

“I can see if you’re talking to me or if you are more loyal to your script than you are to me getting it,” Karton says. “Law school really teaches you that you get done before you’ve made a mistake and they humiliate you. Well, the words are the least of it in one way. Words are a delivery system for something greater.”

So Karton told Katyal to put the pad to one side and try again. Then he told him to hold his hands and look him in the eyes. During his Clio keynote, Katyal recalled thinking, “This is weird.” But he now credits the work he did with Karton with helping him win the case.

Swift has no doubt that bringing in the coach was a turning point.

“When you have the weight of something you truly believe in—that you’ve taken a professional risk for—finding the words in the moment is terrifying,” Swift says. “Josh helped Neal find the words he didn’t write. He helped Neal find them in the moment so they were authentic.”

Not all first-time advocates go to the same lengths as Katyal. But as the day draws closer, every attorney has their own way of coping with the pressure.

Before he quit smoking, retired Supreme Court veteran Michael Carvin could be found outside the offices of Jones Day in Washington, D.C., chomping on a cigar and muttering to himself as he ran through his argument. (He says a client once mistook him for a homeless person.)

André blows off steam by going on long runs and blasting Metallica and Deadmau5 through his headphones. Theodore J. Boutrous Jr., another seasoned Supreme Court lawyer who is a partner in the Los Angeles office of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, remembers getting into a Zen-like state in the days leading up to his first argument in March 2011 in Wal-Mart Stores Inc. v. Dukes by going on long walks and meditating.

Davis was Williams’ first and only case before the Supreme Court. She recalls stress-eating delicious homestyle macaroni and cheese from a local restaurant in the Dupont Circle neighborhood of D.C., and calls the 10 pounds she gained during that period her “Davis 10.”

Roberta A. Kaplan, who in March 2013 argued United States v. Windsor, the landmark case finding the Defense of Marriage Act unconstitutional, barricaded herself away in a tiny office in her New York City apartment in a hoodie and sweatpants to prepare, coming out only to eat or sleep. “I’m not even sure I bathed all that much,” Kaplan says.

Amunson lives in Alexandria, Virginia, with her husband, Andy, and two children, Conall and Fiona, about 10 miles away from the Supreme Court building. In the days leading up to the hearing, she obsessed over the logistics.

What if an accident shut down the 14th Street Bridge and she couldn’t get over the Potomac River? What if she was late for her own argument?

"It was helpful to be totally on my own the night before the argument." - Jessica Ring Amunson

Amunson says the only solution was to book herself into a room at the Grand Hyatt hotel in D.C. “It was helpful to be totally on my own the night before the argument,” she says. “I took a taxi, but I knew if I needed to, I could walk.”

On the morning of his argument, Browning looped his lucky blue tie around his neck. He walked from his hotel to the court, following tradition as he placed his hand on the foot of the bronze statue of Chief Justice John Marshall, which was worn down from all the other advocates having done the same thing.

Kannon K. Shanmugam was an assistant to the solicitor general when on the day of his first argument he donned morning dress and the same silver tie he got married in. Gregory G. Garre, now a partner at Latham & Watkins and a former U.S. solicitor general, put on the gold watch given to him by his father. Boutrous clutched the black leather briefcase his wife, Helen, had given him as a gift as he made his way to court in a taxi.

And on Oct. 5, 2016, Christina A. Swarns slipped on a bracelet with the inscription, “She believed she could, so she did,” which she would repeat in her head as a mantra.

Once Swarns was inside the courtroom to argue Buck v. Davis, she quickly got a sense of the stakes when she heard a commotion and saw Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall’s widow, Cecilia Suyat Marshall, taking a seat to listen to her argument in Buck.

Swarns remembers thinking, “This is huge.” But she had her game face on as she got ready to argue the case, in which defense attorneys called an expert witness who said her client, Duane Buck, later condemned to death for murder, was more likely to commit acts of violence because he is Black.

She faced a sticky moment early on. Less than one minute into her argument, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg interjected: “Didn’t that expert [witness] say ... ‘I don’t think he’s going to be a future danger?’”

"I've heard myself [on the audio recording], and you can't tell what was rattling through my head." - Christina A. Swarns

According to Swarns, the reality was more nuanced. Race was definitely a factor in the expert witness’s opinion, and she wanted to hammer that point home.

“Do I correct this? Do I not correct this?” Swarns thought, before deciding she would have to. “The thought must have been lightning fast because I’ve heard myself [on the audio recording], and you can’t tell what was rattling through my head.”

As Amunson reached the podium on the morning of Oct. 4, 2017, she was acutely aware of her voice reverberating around the chamber. “My voice was shaking. That was making me even more nervous. But as soon as I got that first question, I felt very comfortable,” she says.

Standing at the podium also helped Williams narrow her focus. In her case, she recalls how Justice Antonin Scalia fired question after question at her. And about four minutes in, she says Justice Anthony Kennedy suggested that she was advocating for “federal standards for school behavior in every classroom in this country.”

“At another time in my life, I might have gotten frustrated and angry by that question. But I was like a different person. Looking back, that’s just the first of many times I was under a lot of pressure. I tend to show a pretty calm face, although I’m thinking, ‘I’m going to vomit,’” Williams says.

Once the lawyers settle their nerves and the questions come thick and fast, managing time becomes one of the biggest challenges.

“You’re in some kind of hyperspeed consciousness,” Kaplan says. “It’s not like any other argument I’ve done.”

The Supreme Court allows advocates to make a statement, but after that, it’s a “free-for-all,” Boutrous says.

"Always start with the conclusion, and then go back and explain it. In other words, give them the headline first." -Michael Carvin

For that reason, Carvin tells lawyers to distill their argument into as few words as possible.

“Thirty minutes goes really fast,” Carvin says. “These days, Chief Justice Roberts runs a looser court. But my advice is, always start with the conclusion, and then go back and explain it. In other words, give them the headline first.”

Many of the advocates the ABA Journal interviewed for this story, including Williams, Swarns and Kaplan, won their first cases at the court.

But despite the enormous highs that come with the victories, the losses can linger just as long.

"Our job as attorneys is to be the most effective advocates we can be. But there's an awful lot beyond your control." -Christopher G. Browning Jr.

Browning says an argument always has the potential to go badly. But the justices treat everyone with respect—unless they come to court unprepared or can’t answer basic questions, he says. He notes that even Chief Justice Roberts had a 9-0 loss when he was a practicing lawyer.

“One of his clients asked, ‘How was it that this ended up being 9-0?’ And the response was, ‘There were only nine justices.’ Our job as attorneys is to be the most effective advocates we can be. But there’s an awful lot beyond your control,” Browning says.

Williams, who is now CEO of Equal Justice Works and a former dean of the University of Cincinnati College of Law, feels fortunate to have argued at the court. She notes very few Black women get to appear before the justices, and more experienced members of the Supreme Court bar stand ready to swoop in and snatch cases from advocates with less experience.

“With the benefit of distance and more maturity, I see that it wasn’t a foregone conclusion. It could have definitely gone to somebody else,” Williams says. “But when I thought about the stress—it was incredibly stressful—I thought, ‘I don’t want to do that anymore.’ People can lose their minds under this kind of pressure.”

Ultimately, she believes her first argument prepared her for whatever life threw at her.

“Whenever the going gets tough, I say to myself, ‘Come on. You’re not arguing in front of the United States Supreme Court.’”

Related article: Art Lien sketched court figures for 45 years, from blockbuster cases to the arcane

Photo gallery: The Courtroom Art of Art Lien.