Slow Going: Despite diversity gains, some law firm leaders bemoan lack of progress

Photo illustrations and charts by Elmarie Jara / ABA Journal

Sheila Boston wasn’t the first Black woman to make partner at Arnold & Porter—now Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer. But she still recalls the impact her promotion in 2004 had on other people of color working at the firm.

“They expressed to me how proud they were and that it was a victory for all of us and a great sign of racial progress,” says Boston, who joined the firm as a summer associate in 1992.

Since then, the rate of diversification among law firm leaders has been slow. And for Black women like Boston, who make up less than 1% of law firm partners, it’s been glacial.

“It’s kind of abysmal. We really should be doing better,” Boston says. “Representation is so important. If you can see it, then you think you can be it.”

A series of recent studies have revealed the lack of diversity in law firm partnerships—even after the May 2020 murder of George Floyd spurred the profession to respond to calls for racial justice by launching in-house diversity programs and hiring more chief diversity officers. (See “Inclusion & Equity,” December-January 2021-22, page 44.)

And diversity is front and center of the ABA Profile of the Legal Profession 2022.

The annual report, released in July, offers a snapshot of demographics among the nation’s 1.3 million lawyers.

The report suggests that while there have been modest gains in the last couple of years for women, people of color, LGBTQ attorneys and people with disabilities—particularly at the associate level—the legal profession far from reflects the nation it serves.

ABA President Deborah Enix-Ross says the profession has “come a long way.” She believes the confirmation of Ketanji Brown Jackson to the U.S. Supreme Court “should give us the energy to keep pressing forward.” But she says there is still much more work to do.

“We need our bar associations to be focused in this area. We all need to do what we can both individually and collectively to make sure that the bar is more representative of our communities,” says Enix-Ross, senior advisor to Debevoise & Plimpton’s International Dispute Resolution Group.

Patricia Brown Holmes, the Chicago-based managing partner of Riley Safer Holmes & Cancila, says she’s encouraged that awareness of diversity, equity and inclusion has grown in the last two years.

“The discouraging thing is that we’re moving so slow,” says Holmes, who is also a former prosecutor, defense attorney and judge. “Like, come on people. Let’s do this.”

Glacial Pace

The ABA report states the number of law firm partners who are people of color has grown for 28 consecutive years. In 1993, 2.55% of partners were lawyers of color. In 2021, they made up 10.75%, says the report, relying on data from the National Association for Law Placement, which follows legal hiring and pay.

“Viewed year by year, the change is almost imperceptible,” the 124-page ABA report states. “But viewed over the span of decades, it is easier to see, and it is accelerating.”

Asian Americans appear to have made some of the largest gains—an increase the ABA report attributes to California starting to report the race and ethnicity of its lawyers in 2022. Asian Americans also make up a plurality of partners of color, accounting for 46%; Hispanics make up 31%; and Blacks make up 24%.

James Leipold, who retired as NALP’s executive director in October, believes the call to action in summer 2020 accelerated change, and he says there are other reasons to be encouraged.

The 2021 class of summer associates was the most diverse ever, Leipold says. According to NALP’s 2021 Report on Diversity in U.S. Law Firms, the percentage of summer associates of color grew by almost 5 percentage points in one year, which is the largest gain in the 29 years it has tracked the data.

But at the partnership level, there are sharp disparities by gender, race and ethnicity, Leipold says.

In 2021, Black women and Latinas still represent less than 1% of all partners in American law firms, Leipold notes. And women make up only 25.92% of all partners, while women of color make up just over 4% of all partners.

“The overlap of race and gender is the worst because it’s like a double whammy. We see women of color least well represented,” Leipold says.

The ABA report, relying on NALP data, states that the percentage of LGBTQ lawyers at law firms is also growing slowly, going from 1.9% in 2011 to 3.7% in 2021. But the ABA report cautions that “no reliable statistics are available on the total number of lawyers who identify as LGBTQ in the legal profession overall.” As for lawyers with disabilities, the number is so small (just over 1% of lawyers at law firms) that NALP cautions it is “difficult to draw any conclusions about trends.”

Retaining talent

Kent Zimmermann, a law firm consultant with the Zeughauser Group, says many firms are coming around to the idea that having diverse talent can lead to better results and give them a competitive advantage.

He adds that there have been great strides in the recruitment and hiring of diverse lawyers. But when it comes to retaining talent, many law firm leaders would admit they are falling short.

Particularly in law firms struggling with diversity, it can be challenging for a minority lawyer to be a “trailblazer and be highly successful in a firm,” Zimmermann says.

“Lawyers who are in a position to include other lawyers in the firm on their matters or share credit often are more likely to do that with people who they know and trust,” Zimmermann says. “And often lawyers build trust with people like them, rather than people who aren’t like them.”

To foster diversity from top to bottom, law firms need to do a better job of making firms more inclusive and retaining female attorneys and lawyers of color, Boston says.

Although she credits Arnold & Porter with helping her get to where she is today, she says at the beginning of her career, she sometimes struggled to feel like she belonged. And she says other lawyers’ conscious and unconscious biases can prevent attorneys of color from advancing, including perceptions that they are not as competent and do not write as well as white attorneys.

“When you’re an attorney of color, especially a woman of color, you can be treated as ‘the other,’” Boston says. “That can be damaging as you progress in your profession. But it also can wreak some havoc on you emotionally and psychologically.”

Boston says impostor syndrome can be acute for women and lawyers of color, and there is an added pressure piled on them to do well. Despite the plaudits that came her way when she made partner, Boston remembers a colleague questioning why she moved up. And it stung.

“I hate to admit it, but when I look back and reflect on that time, it really bothered me, and it adversely affected me for a couple of years,” Boston says.

According to Holmes, there also are barriers that women, people of color and others from underrepresented communities face as they build books of business.

“To make partner in a firm, it’s simple: You learn how to do the work, you get clients to hire you to do the work, and you bring in profit that can be shared among the partnership,” Holmes says. “The difficulty comes when women and minorities can’t get the clients.”

Paulette Brown—who in 2015 became the ABA’s first African-American female president and was a senior partner and chief diversity and inclusion officer at Locke Lord before retiring in 2021—says there are often fewer sponsorship and mentorship opportunities for women and women of color.

Traditionally, she says, it was less likely that white male partners would take women of color under their wings and help them become rainmakers. Instead, diverse lawyers are more reliant on outside professional associations and groups.

“It’s not like it’s never happened,” Brown says. “But it’s not something that is standard practice.”

Jeanine Conley Daves, office managing shareholder of Littler Mendelson’s New York City office, says the biggest rainmakers in a firm are often those who have had business handed down to them.

She says women and women of color can find themselves “closed out of the system,” so they can’t collaborate with other shareholders to develop their own books of business or get credit for working on client matters originated by other attorneys—key factors firms look at when considering compensation or promotions.

Boston suggests firms should consider other metrics when deciding who will make partner, such as an attorney’s leadership qualities and nonbillable activities like mentoring and associate training.

“I understand books of business are a major criteria, but it certainly shouldn’t be the only one,” Boston says.

Institutional barriers

The ABA report dedicates an entire chapter to women in the legal profession and notes that since 2016, women have outnumbered men in ABA-accredited law schools.

“Although more than half of all law school graduates are women, the number of women in senior leadership roles at U.S. law firms is far less than half—even with the number slowly edging up in recent years,” the report states.

The percentage of female partners has risen every year since 2012. Roughly 22% of all equity partners were women in 2020, up 7 percentage points from 2012, and 32% of nonequity partners were women. But only 12% of managing partners were women.

Perkins Coie’s chief diversity and inclusion officer, Genhi Givings Bailey, says there are many institutional barriers preventing women and people of color from feeling “like they are a part of the fabric of the organization.”

Those barriers include inequities in pay and biases in how women are evaluated and considered for promotion and succession planning, according to the 2021 National Association of Women Lawyers Survey on the Promotion and Retention of Women in Law Firms.

There also can be a lack of transparency about how compensation is decided, Bailey adds.

“In some firms, it’s a closed black box. You don’t even know what goes into the process—and if there is bias in that system or in that process, what the impact is on women and people of color,” Bailey says.

Although women have almost achieved parity in pay at the associate and nonequity partner levels, there is still a big gap at the equity partnership level, where women on average received 78% of the compensation of their male counterparts, the NAWL report states.

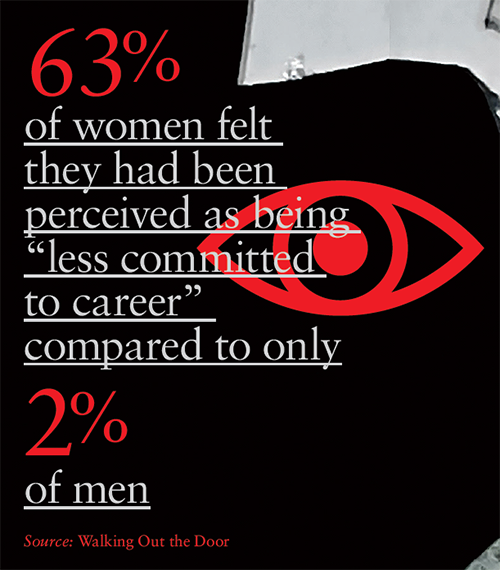

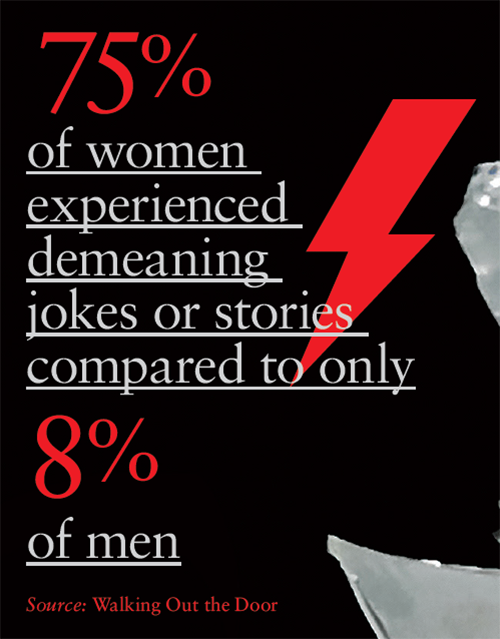

A 2019 ABA study cited in the report, Walking Out the Door, also offers a few clues as to why a majority of women in law schools is not reflected in the profession.

The survey of more than 1,200 lawyers found that while an overwhelming majority of men agreed that female lawyers were being treated fairly, women disagreed.

Although 79% of men agreed that their law firms had succeeded in promoting women into equity partnership, only 48% of women did. When asked if their firms had successfully retained experienced women, 74% of men agreed, but only 47% of women agreed. Additionally, the study found that 63% of women felt they had been perceived as being “less committed to career” compared with only 2% of men, while 67% of women said they experienced a lack of access to business development opportunities as opposed to 10% of men. Women also reported being subject to a hostile work environment: 75% said they had experienced demeaning jokes or stories compared with only 8% of men.

Mandating diversity

J. Danielle Carr, chief officer of inclusion at the law firm Lowenstein Sandler, says making equity partner is the “holy grail.” But she also says that women and people of color, LGBTQ attorneys and people with disabilities still face an uphill task getting there.

Carr says clients should apply pressure on law firms and insist they place minorities in leadership positions.

Big business has reckoned with its own diversity problems. But in recent years, Novartis, HP Inc., Meta Platforms Inc. and other corporate clients have warned they would take their business elsewhere or even cut fees if they did not see firms taking action on gender and racial diversity.

As far back as 2017, HP said it would temporarily dock fees for firms that did not meet its diversity benchmarks.

Meta, the parent company of Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp, uses diversity data to rank law firms, using benchmarks on staffing, opportunities given to diverse attorneys, initiatives at the firm and the makeup of a firm’s incoming partner class.

“Those diversity scores do matter because if we know the law firms are equally committed to it the way that our legal department is, that’s just going to be even more reason for us to invest in a deeper relationship with those law firms,” says Jeremiah Chan, director and associate general counsel at Meta.

Microsoft launched a law firm diversity program in 2008. In 2020, the tech company increased its focus on demographics of law firm leadership, stressing the need to include more Black and Hispanic lawyers in partnerships.

According to Microsoft, the initiative stems from its “commitment as a signatory” to ABA Resolution 113, passed in 2016 to encourage legal service providers and buyers of legal services to expand diversity.

Perkins Coie is one of the law firms that has partnered with Microsoft. And Bailey says the tech company recognizes that “moving the needle on these issues can be challenging, and it takes time.”

Bailey’s firm has also committed to the Mansfield Rule, which was named after Arabella Mansfield, the first woman admitted to practice law in the United States. Advanced by Diversity Lab, the rule takes its lead from the NFL’s Rooney Rule. The Mansfield Rule says 30% to 50% of candidates applying for leadership positions or programs promoting leadership roles in firms should come from underrepresented groups. According to Diversity Lab, more than 270 law firms in the U.S. and Canada, 15 U.K. law firms and 75 legal departments have signed on.

To advance diversity in the profession, law firms have launched in-house initiatives. Boston says her firm partnered with the National Bar Association on a program aimed at retaining and advancing Black lawyers. Two other programs at her firm advance opportunities by increasing the pipeline of students of color who want to work in the profession and promoting equity in education.

Thrive Scholars’ Law Pathway, another pipeline program, extends the profession’s reach into high schools to identify the lawyers of the future. The pipeline initiative, created with the help of the Zeughauser Group, identifies high school juniors of color who want to pursue careers in law and then helps them progress from college to top law schools. The program also offers lawyer mentorship from the likes of Holland & Knight; Kirkland & Ellis; Pillsbury; and Shearman & Sterling.

But despite these initiatives, former ABA President Robert Grey, president of the Leadership Council on Legal Diversity, says diversity efforts have sometimes been sporadic and inconsistent.

“We haven’t had consistent leadership on diversity. We haven’t had consistent expectation of results. We haven’t had consistent application of principles and processes. Sometimes we excel in this area. Sometimes we don’t,” Grey says.

Bailey says changing people’s behaviors is the hardest part. “We can do research, we can crunch the data, we can share the feedback. But at the end of the day, the most important thing that’s going to move the needle is if we all change our behaviors.”

View from the bench

The ABA report also notes the lack of diversity among the more than 1,400 Article III judges on the federal bench, which the report notes are “overwhelmingly male and overwhelmingly white” but finds “times are slowly changing.” According to the report, 91% of all federal judges in 1980 were white, compared to 78% as of July 1, 2022. In that same period, women have gone from 5% of the federal bench to nearly 30%.

The picture is similar in state courts. A May 2022 Brennan Center for Justice study found men make up the majority of judges in state supreme courts. According to the study, 18% of state supreme court justices were minorities, and 41% of them were women.

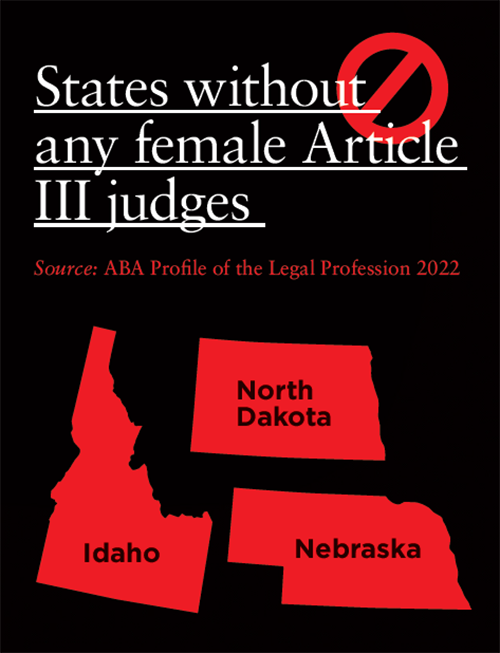

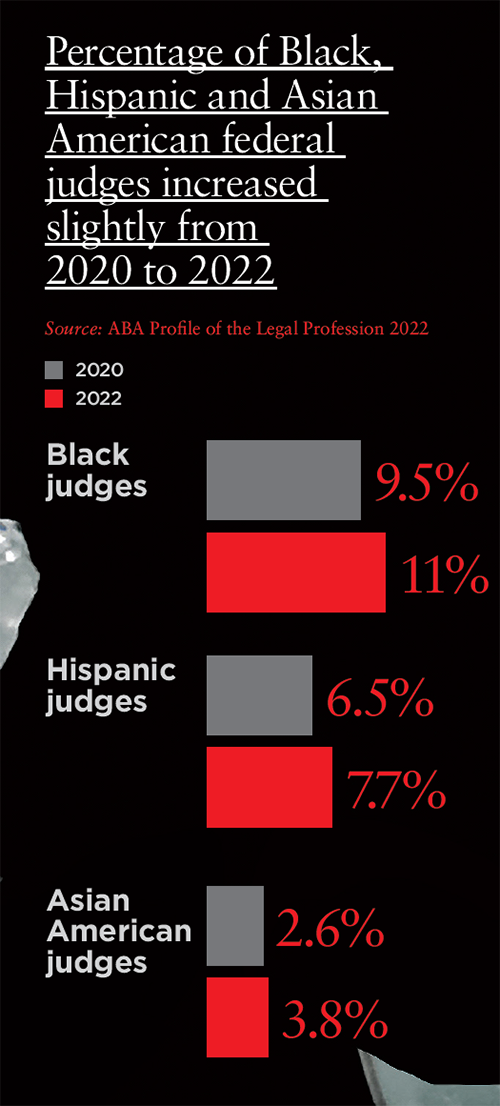

The ABA report found that from 2020 to 2022, the percentage of Black, Hispanic and Asian American federal judges increased slightly, going from 9.5% to 11% for Black judges; 6.5% to 7% for Hispanics; and 2.6% to 3.8% for Asians. But according to the ABA report, 15 states have no federal trial judges of color, and in three states—Nebraska, North Dakota and Idaho—there are no female federal trial judges. There are only 59 Black women serving as Article III federal judges in the entire country, the report adds.

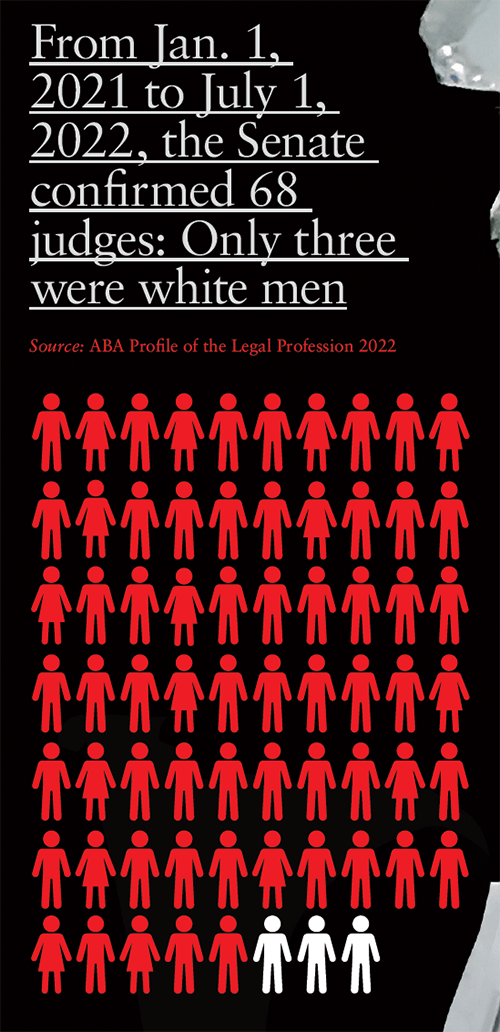

But the federal bench has become slightly “less homogeneous,” according to the report, because of new appointments of women and people of color. From Jan. 1, 2021 to July 1, 2022, the Senate confirmed 68 judges. Only three of those were white men.

Another group that dominates the federal bench? Ivy Leaguers. Eight of the nine justices on the Supreme Court came from Harvard and Yale. And the ABA report notes that 232 judges, or 18%, have Ivy League law degrees.

“Public institutions produce judges who have a different experience coming from a public education,” National Judicial College President Benes Z. Aldana says. “To promote greater public confidence and trust in our judiciary, we need to look at that.”

In the past, BigLaw’s reliance on elite schools for recruiting and hiring lawyers and the impact that can have on diversity has been in the spotlight. Holmes says there are great lawyers “who were middle of the class” and “even great lawyers who may have been bottom of the class.”

She says firms need to be less judgmental and give lawyers with different educational backgrounds a chance to “show what they can do.”

Still, Bailey is cautiously optimistic. She says that more than two years after calls for racial justice, she sees no evidence that law firms are scaling back their efforts on diversity.

“I think it’s only a matter of time before we start to see better numbers in representation of attorneys of color among the partnership ranks,” Bailey says.