‘Sext’ Education: States Look for Ways to Chastise Teens for Bawdy Cellphone Shots

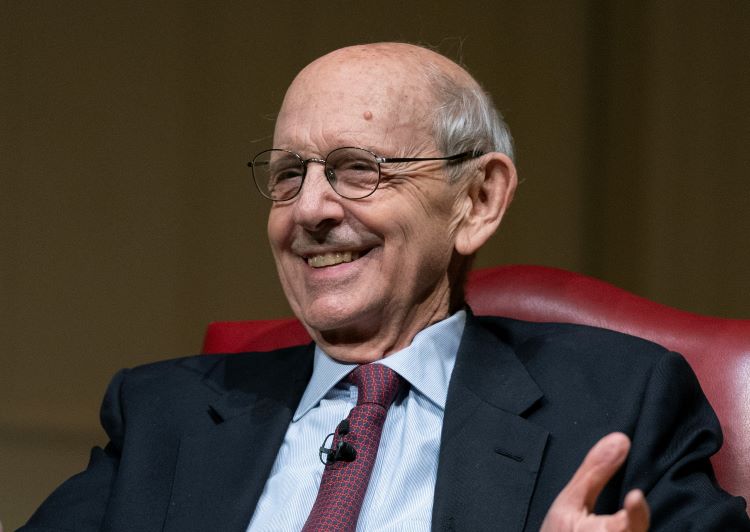

Witold Walczak of the Pennsylvania ACLU with MaryJo Miller, who filed suit against the Wyoming County DA after he threatened to prosecute her daughter and two other teens. Photo by AP Photo/Matt Rourke

When school authorities in Wyoming County in northeastern Pennsylvania learned three years ago that high school students were sending nude or scantily clad images of each other via cellphones, they were confronted with one of the country’s first major “sexting” scandals.

Among the photos was one of two girls in bras, while another showed a teen wearing a white towel wrapped under her breasts.

Former District Attorney George Skumanick Jr. threatened to prosecute all of the students involved—those who sent the images as well as the recipients—on child pornography charges unless they attended a program run by the probation department.

Most teens complied, but three girls and their families sued, seeking an injunction banning prosecution. Represented by the American Civil Liberties Union of Pennsylvania, the teens argued that the prosecutor’s stance violated their First Amendment right of free expression. Additionally, they said, the program would violate their free-speech rights because they would have been required to write an essay about why what they did was wrong.

U.S. District Judge James Munley in the Middle District of Pennsylvania agreed with the teens and, in March 2009, enjoined prosecution. He said the authorities couldn’t constitutionally require the teens to write an essay condemning their behavior. Imposing such an obligation would violate their free-speech rights and also would violate their parents’ rights to raise their children free of governmental interference, he said.

The 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals at Philadelphia upheld that relatively narrow ruling, but punted on the larger question of whether the photos were unlawful child pornography or protected under the First Amendment. Soon after that decision, the case settled and Munley entered a permanent injunction against prosecution.

THE LEGISLATIVE RESPONSE

The case law is far from settled about whether authorities can constitutionally prosecute teens sending or receiving sexually explicit photos. Nevertheless, states are enacting their own statutes, trying to carve a middle path between completely decriminalizing sexting on one hand and prosecuting teens as sex offenders on the other.

Bills or resolutions have been introduced in at least 20 states, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, and new legislation has been enacted in at least 10 states. Most of those bills aim to lessen the penalties for sexting by treating it as a misdemeanor or other low-level infraction instead of a felony sex offense.

In Illinois, for instance, teens who forward or post online racy pictures of their underage classmates would get juvenile court supervision that could result in mandatory counseling or community service.

“As the Internet explodes and people are taking advantage of it, these images hang around forever,” says state Sen. Ira Silverstein, a Chicago Democrat. “Once they’re disseminated, they can ruin somebody’s career.”

And in New Jersey, the state assembly unanimously passed a bill in March that would allow first-time offenders to undergo a diversionary program.

In Ohio, Republican Rep. Ron Maag introduced a measure that would make it a misdemeanor for minors to recklessly create, possess or send nude photos of other minors.

Maag says that some legal intervention is needed because sexting poses hazards to teens. “What about the real pedophile,” he says, “who might be able to pick it up on the Internet and track you down?” He argues that his measure would give prosecutors an alternative to bringing child pornography charges and convictions that carry mandatory registration as a sex offender.

But some advocates say that hauling minors into the criminal justice system for taking or sending racy photos is dangerous even if the charge is only a misdemeanor. Marsha Levick, deputy director and chief counsel of the Juvenile Law Center in Philadelphia, points out that getting hauled into court in itself can damage teens.

“If my daughter were arrested for sharing a silly photo with her boyfriend and hauled off to court by a male DA, and went before a male judge and a male probation officer—I can’t think of anything more traumatic,” she says. “The concern about kids’ foolish use of technology is entirely legitimate, but why wouldn’t we want to think about education? Why would we waste judicial resources and traumatize our kids by putting them into the justice system?”

THE FEDERAL APPROACH

Even if new laws are enacted by the states, those laws wouldn’t necessarily prevent federal prosecutions. In February, U.S. District Judge Jennifer Coffman in the Eastern District of Kentucky ruled that federal laws criminalizing the distribution of sexually explicit photos of children apply regardless of the age of the creators or senders.

In that case, a 14-year-old girl sued three 14-year-old boys for allegedly distributing a sexually explicit video of her that she had made and sent to one of them. She argued that she is entitled to civil damages for violations of federal law. The boys asked for the lawsuit to be dismissed, arguing that Congress didn’t intend for the statute to apply to teens.

Coffman denied the motion to dismiss. “Nothing in the plain language of the statutes or their legislative history indicates that Congress intended [the statutes] to apply only to the conduct of adults. Both statutes prohibit creation, possession and transmission of child pornography by any ‘person,’ ” the judge wrote.

The issue isn’t going away. The Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project reported in December 2009 that 4 percent of teens ages 12 to 17 who own cellphones have sent nude or nearly nude images or videos of themselves, while 15 percent in that group have received such images of someone they know.

When these photos come to the attention of authorities, prosecutions sometimes follow.

For instance, Antjuanece Brown of Tigard, Ore., then 19, was convicted last year of a felony for exchanging allegedly pornographic photos with her 16-year-old girlfriend. Brown was sentenced to three years’ probation, assessed $3,000 in court fees, and ordered to keep away from the younger girl until she turns 18.

These types of cases confound legal experts because the situation doesn’t fit people’s conception of child pornography. In a 1982 case, New York v. Ferber, the U.S. Supreme Court said that child porn wasn’t protected by the First Amendment. The court held that such material victimized minors involved in its production.

That decision, however, dealt with whether the child pornography laws violated adults’ rights to free speech. At the time, few people contemplated that teens would one day send photos of themselves to others.

“There’s a long history of government efforts to prevent dissemination of material harmful to minors,” says John Palfrey, co-director of Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet & Society. “But not in the context of student-to-student speech. That’s why this sexting stuff can be so challenging.”

Palfrey adds: “It’s not the paradigm that legislatures have attempted to deal with, which is adults doing this to kids.”

At the same time, some observers say that teens who send explicit photos of themselves are leaving themselves vulnerable to victimization. For example, a recipient could forward the photo to other people or post it online. In one high-profile tragedy, 18-year-old Jessica Logan of Cincinnati committed suicide after a photo she sent to her boyfriend was more widely circulated.

“It’s a very difficult issue,” says Parry Aftab, a Wyckoff, N.J.-based child advocate and cyberlaw expert. “An image takes on a life of its own and has the power to do serious damage to the people in it.”

Aftab says she doesn’t believe that teens should be prosecuted for taking photos of themselves, as opposed to sending them. “The laws run too hot and too cold here,” Aftab says. “You want a situation that gives prosecutors and law enforcement the ability to do something without going overboard.”

But civil libertarians say that prosecuting teens for taking photos of themselves, or voluntarily sharing them, violates their free-expression rights. “Our position is that the consensual exchange of naked or semi-naked pictures between two minors should not be a crime at all,” says Pennsylvania ACLU legal director Witold “Vic” Walczak, who represented the teens and their families. “If you’ve got nonconsensual transmission, that could be a form of harassment.”