Sept. 22, 1919: The Great Steel Strike of 1919

George Grantham Bain Collection (Library of Congress)

As 1918 drew to a close, Americans began a “return to normalcy.” To most, this meant an end to the sacrifices of the Great War. But to U.S. industry, it meant a renewal of deep-seated conflicts between labor and capital. The National War Labor Board had helped set aside disputes in the vital coal, steel and transportation industries, and with its expiration a new generation of corporate managers grew anxious to throttle back the emerging power of labor unions.

Beginning in August 1918, the American Federation of Labor had begun to pull together more than two dozen disparate trade organizations that made up the rank and file at the nation’s steel mills. Though the AFL was considered moderate compared to the “Wobblies” of the Communist-driven Industrial Workers of the World, the rise of Bolshevism in Europe allowed the nation’s industrial giants to win the sympathy of a public that feared a potential breakdown of American economic and social institutions at the hands of radicalized workers—many of them immigrants. There was violence.

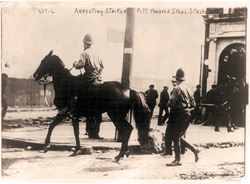

In late August 1919, union organizer Fannie Sellins was murdered in western Pennsylvania; within days, her blood-soaked picture was a fixture in union halls. In early September, a wildcat strike by Boston police left the city to hooligans. And by the time steelworkers walked out on Sept. 22, they found themselves pitted against not only management but also a hostile public unsympathetic to their demands for an eight-hour day, a six-day workweek and the right to organize without being harassed. At first, the strike seemed successful. An estimated 365,600 workers deserted their posts at steel mills and furnaces. But almost everywhere, local police and state militia converged on picketers. Judges upheld bans against union gatherings. State legislatures stepped up passage of laws against “criminal syndicalism,” aimed at curbing the volatile rhetoric of trade unionism.

By Jan. 8, the Great Steel Strike was over, but the laws against criminal syndicalism remained a potent tool against union organizers until they were struck down by the Supreme Court in 1969.