Sept. 10, 1846: The Sewing Machine Patent War

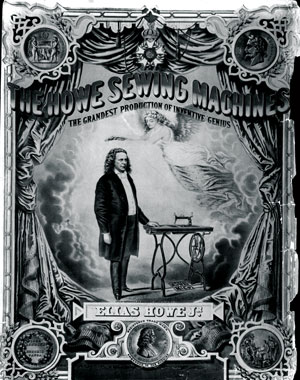

Bettmann/Corbis

By the time Elias Howe, part-time inventor and full-time ne’er-do-well, received U.S. Patent No. 4,750 for a sewing machine, he and his family were destitute. The machine he had hoped would revolutionize the production of textile goods in New England was regarded by the public as little more than a mechanical marvel, a curiosity that could sew seven times faster than the most experienced seamstress. Moreover, its efficiency made tailors fearful, and its price—built by hand for $300—made textile manufacturers skeptical of its practical application. When his investor, a close friend, decided he could support Howe no longer, Howe decided to look abroad.

Howe built another machine and shipped it to England with his brother, Amasa, to solicit funds. But the best Amasa could manage was an arrangement with a corset manufacturer, William Thomas, who persuaded Howe to follow his brother to England to adapt the machine to corset production. When Howe and Thomas had a falling out, Howe and his family were still broke—so broke he had to pawn the original machine and its letters of patent, just to have money enough to repatriate.

Landing in New York in 1849, Howe discovered that in his absence, imitations of his patented sewing machine were being manufactured throughout the industrial North. Some were still exhibited as entertainment at fairs and expositions. But some were being deployed to make shirts and pants in a growing number of mills and sweatshops.

Howe decided to enforce his patent. With the help of a new investor, he redeemed his original machine and patent letters and began serving notice to the largest sewing machine manufacturers. Howe demanded that they cease their infringement or pay him a licensing fee; and with the sewing machine market building momentum, most readily agreed.

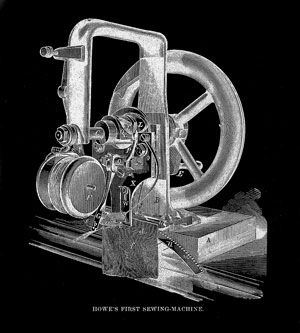

The earliest Howe sewing machine. Creative Commons, State Library of Massachusetts.

One exception was Isaac Merritt Singer, who decided to force Howe to defend his patent in court. Their explosive trial took place in 1854. Singer, a former actor and entrepreneur, argued that Howe’s invention—the unique use of a shuttle and double-threaded, curved needle—was simply a marginal improvement of devices created before his. But after a lengthy litigation that generated 3,575 of pages of motions and depositions and briefs, Howe—now on his way to becoming a millionaire—was declared the unquestioned inventor of the sewing machine.

Establishing the primacy of Howe’s patent, however, did not bring peace among sewing machine manufacturers. In what amounted to the first patent war, sewing machine manufacturers began suing each other for infringement of patents—hundreds of them—awarded for improvements on Howe’s machine.

An accord was reached in 1856 that brought together Howe and the major manufacturers in a confederation, which they called the Sewing Machine Combination. The group agreed to end the lawsuits against each other, allow common use of their various patents, and litigate against infringers who violated the patents in their patent pool. Until 1877, when most of their patents expired, the Sewing Machine Combination was both feared and despised. But their overlapping claims are regarded as the first “patent thicket” and their agreement the end of the first patent war.