Who's to blame when self-driving cars crash?

Shutterstock

On May 7, 2016, Joshua Brown made history. The Canton, Ohio, resident became the first person to die in a self-driving car.

Brown, 40, had turned on Autopilot, the autonomous driving system of his Tesla Model S, and set the cruise control at 74 miles per hour. As his car raced down a highway west of Williston, Florida, a tractor-trailer came out of an intersecting road.

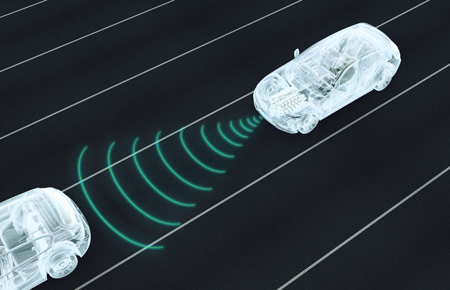

Tesla’s Autopilot is a technological marvel. It controls the car, using radar and cameras to scan the road. It keeps the car within lanes on highways. It brakes, accelerates and passes other vehicles automatically.

According to one of Tesla’s public statements, the camera on Brown’s car failed to recognize the tractor-trailer crossing the highway against a bright sky. As a result, the car did not brake, nor did it issue any warning to Brown. The car crashed into the trailer, killing Brown.

The automobile’s self-driving system was not at fault, according to an investigation conducted by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. The agency found that Autopilot was designed to prevent Tesla cars from rear-ending other vehicles but was not intended to handle situations when vehicles crossed the road from intersecting roadways. Thus, there were no “defects in the design or performance” of the system, the NHTSA concluded.

Brown was responsible for the crash, according to the agency. If he were paying attention, he would have seen the truck crossing the highway and had at least seven seconds to respond—sufficient time to avoid the collision.

No one knows for sure what Brown was doing in the last seconds of his life. But the other driver told police he heard a Harry Potter movie playing in the crushed automobile after the crash.

Tesla avoided liability for his death because Autopilot was intended to aid, not replace, human drivers. The technology, however, is changing. Google, Mercedes-Benz, Tesla, Uber and Volvo are some of the companies working to develop fully autonomous cars, intended to drive themselves without human intervention. Google’s prototypes don’t have steering wheels or brake pedals.

who’s really responsible?

Matthew T. Henshon, a partner at Henshon Klein in Boston and chair of the Artificial Intelligence and Robotics Committee of the ABA Section of Science and Technology Law, says “people haven’t really thought ... through” who—or what—will be liable when fully autonomous cars crash, resulting in injury or death.

“This is going to burgeon into the most significant subject matter of the 21st century,” says Paul F. Rafferty, a partner in the Irvine, California, office of Jones Day.

The law, as it stands now, is simple. Human beings cannot delegate driving responsibility to their cars. In self-driving cars, a human must be ready to override the system and take control.

This rule has to be updated, according to the NHTSA’s September 2016 report on autonomous vehicles. The organization suggested that different legal standards should apply, “based on whether the human operator or the automated system is primarily responsible for monitoring the driving environment.” For the latter type of vehicles—dubbed “highly automated vehicles”—the HAV system should be deemed the driver of the vehicle for purposes of state traffic laws, the NHTSA recommended. In other words, the HAV, not its passengers, should be criminally liable when traffic laws are violated.

There are good policy reasons for this, says Jeff Rabkin, a former prosecutor and now a partner in the San Francisco office of Jones Day. “If a passenger has no way to operate the vehicle, prosecuting the passenger would not serve any of the purposes of criminal law,” Rabkin says.

Similarly, it wouldn’t make a lot of sense to impose civil liability on the human occupants when the HAV has an accident. The NHTSA therefore has encouraged states to revise their tort laws to hold HAVs liable when there are crashes.

Sharing the blame

Holding an HAV accountable is easier said than done. “Multiple defendants are possible: the company that wrote the car’s software; the businesses that made the car’s components; the automobile manufacturer; maybe the fleet owner, if the car is part of a commercial service, such as Uber,” says Gary E. Marchant, director of the Center for Law, Science and Innovation at the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law at Arizona State University. “How would you prove which aspect of the HAV failed and who should be the liable party?”

Technical forensic investigations will be required. “Attorneys will need to hire experts to download the black boxes from the vehicles and evaluate the precise system failure that caused the accident—a time-consuming process that will surely add additional expense to litigation,” says Jeffrey D. Wolf, a partner at Heimanson & Wolf in Los Angeles.

This will complicate criminal prosecutions of HAV companies—and transform civil accident cases. Relatively simple negligence suits that involve two parties will be replaced with complex, lengthy and expensive product liability litigation with multiple defendants.

“What have been, to date, mostly straightforward cases of fault against an owner for improper handling of a car will now become cases that are much more expensive,” Wolf says.

As a result, many tort victims will be unable to obtain justice. “It will be difficult to accommodate driverless vehicles under the current common-law framework. We will need a new statutory scheme because otherwise it will be too costly for individuals to prosecute [tort] claims,” says Wayne R. Cohen, founder and managing partner at Cohen & Cohen in Washington, D.C.

He favors a strict liability regime that covers HAV-makers and subcontractors. “Otherwise, you will impede access to the civil justice system for anyone who is injured,” Cohen says.

Other experts worry that a strict liability regime would put an unfair burden on manufacturers of HAVs. “There will be far fewer accidents with HAVs, but when they occur the vehicle’s manufacturer will be sued. So carmakers will have more liability than they do now for making a safer product,” Marchant says.

Benefits come WITH a cost

A strict liability regime could discourage companies from making HAVs. But public policy should encourage manufacturers of HAVs because studies have repeatedly concluded they’re far safer than human-driven cars.

A 2013 study by the Eno Center for Transportation (a nonprofit think-tank in Washington, D.C.), estimated that if 10 percent of the cars on U.S. roads were HAVs, 1,100 lives would be saved annually. If 90 percent of the cars were HAVs, 21,700 lives would be saved each year.

HAVs are expected to provide other benefits to society: easing traffic congestion; shortening travel time; burning less fuel; lowering emissions; and providing mobility to those who cannot drive, such as seniors and people with vision problems. If HAVs constituted 90 percent of cars on U.S. roads, the nation would save more than $355 billion per year, the Eno Center estimated.

Because a negligence standard might make it too expensive for crash victims to obtain justice and a strict liability standard might discourage companies from putting HAVs on the road, some people are contemplating other, less traditional methods for handling HAV tort liability. “Perhaps the creation of a no-fault system would be best, funded by buyers of autonomous vehicles or by a percentage of state motor vehicle fees,” Rafferty says.

A similar no-fault system was created to protect another socially beneficial product. “Vaccines made people safer, but there was great liability when something went wrong, so we had to change the liability regime,” Marchant says.

In 1986, Congress required vaccine-makers—in exchange for legal protections—to contribute to a no-fault compensation fund. Sufferers go before special vaccine courts that can’t award punitive dam-ages, only compensation. “They may need to set up something like that for driverless cars,” Marchant says.

Some experts warn it’d be premature to enact laws now. “Legislation changes slowly, and technology changes fast. Legislation can become obsolete very quickly,” Rabkin says.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.